Have I managed it? Have I published the next post before the previous one is filled with comments complaining about the lack of wrecks? And surely some pedant pointing out that I mentioned anchorages plural but described only one? To both categories of comment I reply: you don’t win more than one award by not being specific with your titles: that was Part One, this is Part Two. There will be wrecks, and another weird anchorage. And for the truly hard of title-reading, I will arrive in Wick where there will be a warm welcome, whence I will catch a 4.5 hour rail replacement bus to Inverness, stay the night in an improbably cheap ‘hotel’ prior to catching the 9 hour train direct to King’s Cross, which was full before it left Kingussie and now has drunken stag parties sitting on the floor between me and the cafe, so I have no alternative but to write two posts in one journey to take my mind off the awful reality of my surroundings. None of that begins with W though, so it’s not in the title.

You’ll remember (because I only wrote it five minutes ago, although it is just possible that the train will not be so delayed that I finish this post before it arrives) that we finished dinner with our new friends imagining we were in a yacht club not a bird observatory, and so it was that for the first time on this entire trip we had an actual race agreed for the next day. Sadly the entrants were going to start at different times and finish in different places, one of them uncertain about where that was going to be, so it was more of a race about doing things as best we could so that we could brag when we surely bumped into each other again on the way south. So it was that Tim and I spent most of the rest of the evening poring over charts and weather forecasts and tide diagrams trying to second guess when the wind would shift and which side of the wind and tide we needed to be when it did so that we could pick up the best lift to our particular finishing line on the island of Westray, the northwesternmost of Orkney.

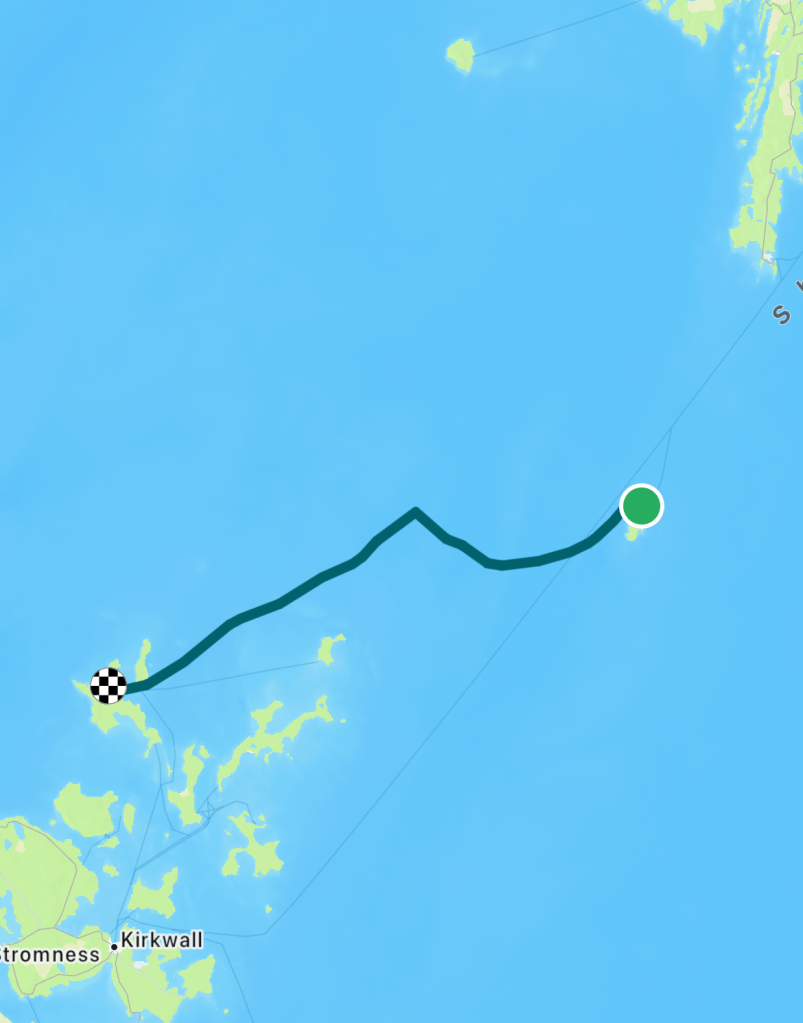

Without wishing to sound smug (why do people write that? Of course I wish to sound smug) I have to say that we pretty much nailed this race on every point. I only wish we could have been so world-beating when sailing together in actual races, but that was a very long time ago now and I for one probably drank more beer the night before which may have clouded my judgement on one or two occasions. On this clear-headed morning we cunningly headed round the north end of Fair Isle (Tim’s idea) so as to get the best of the Southwesterly on port tack, then held our nerve as it headed us before tacking onto starboard on the inside of the shift and laying the finish line comfortably in one. Unfortunately our skill not only materialised decades too late, we didn’t see another boat the whole day, so we could only claim a moral victory until we bumped into Stephen and friends – of course – in St Magnus’ Cathedral a few days later where he also claimed victory. There was no protest committee so we have to call it a draw, but we’re convinced it was a draw in our favour.

I say we saw no other boats, we saw pretty much nothing at all until the last half hour as we sailed in and out of fog banks and rain squalls all day, which rather took the edge off my smugness until we were safely tied up in Pierowall Harbour. Immediately we were struck by the differences between Orkney and Shetland: in spite of Westray being the furthest island from the Orkney mainland there was more than one house, a selection (OK, two of each) of shops, cafes and pubs/hotels/bars and an award-winning fish shop. Sadly these were all about a mile away around the bay and, exhausted by such top-drawer navigation combined with tacking once and taking reefs in and out about a hundred times, we postponed that cornucopia of retail pleasures for the next day when it was – surprise to nobody – forecast to be too windy to sail.

Indeed it was, and as ever the response to too much wind is to hike for miles across windswept beaches and windswept cliffs, this time sufficiently windswept as to make a one-way ticket to the boiling seas below a distinct possibility. We did see our final puffins of the trip, and also the rather scary prospect of what’s called The Gentlemen’s Cave, as it’s where various Jacobite gentlefolk are supposed to have hidden for some months. I really hope for their sakes that it was the summer.

It was already palpably warmer than I had ever been in Shetland, but we were still in the Northern Isles (as Orkney and Shetland are collectively called) so rain was never far away and we took the tough decision not to walk a mile and back in a downpour and gale for fish and chips. I’m glad we stayed on the boat: not only was it dry and the curry tasty but we also got to witness the intense rivalry that is Westray vs Papa Westray, its much smaller neighbour, in their inter-island games, or at least the apres-inter-island games. This would appear to involve drinking as much beer and whisky as possible, carrying what was left with you along with your visiting opponents in a fleet of cars down to the pier so that you can wave them off while drinking more beer and whisky and variously hallooing at each other and roaring with laughter while the ferry honks and the wind howls. It’s only a 20-minute journey to Papa Westray but I swear they were still hallooing and roaring halfway across Papa Westray Sound.

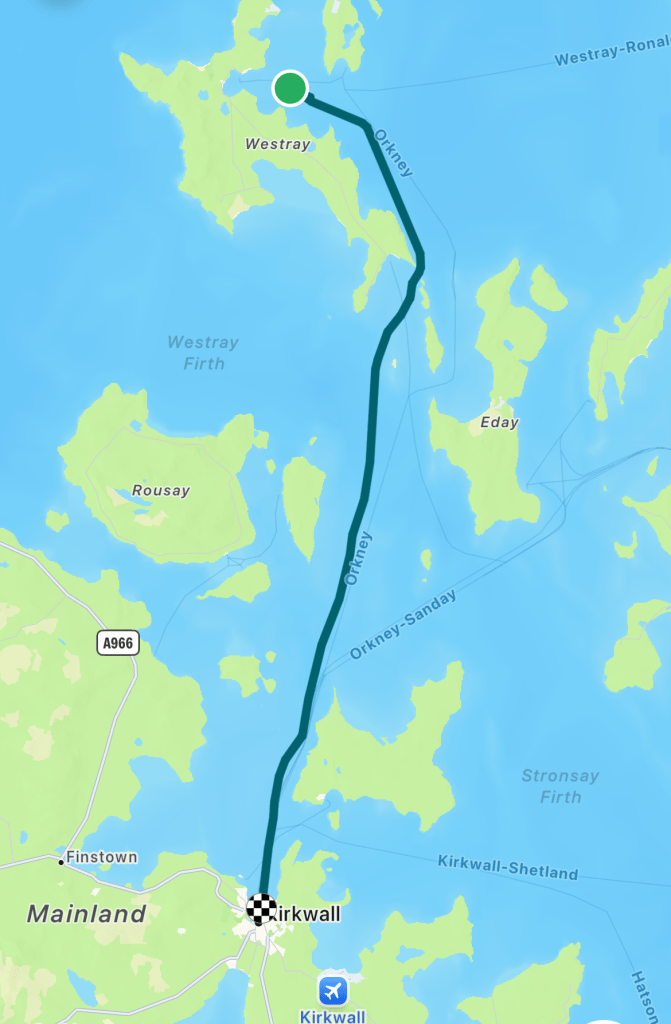

No such hilarity for us: we were wrestling with the legendary Orkney tides and another typically challenging weather forecast. It was going to blow hard for a few days, starting after lunch the next day (I love the way the wind picks its transition points around mealtimes). We’d planned to leave early to get to Kirkwall in good time but the cheery marina volunteer (the three marinas in Orkney are run by volunteers, amazingly) who owned the Contessa 32 next door, so commanded a degree of respect, assured us that we should leave around low water or face punching a punchy tide all the way. Low water = 1pm = lunchtime. Just in time for the big blow. But also, the sailing readership will have spotted, 12 hours earlier, and so did Tim, whose navigational skills are not confined to racing, and so it was that we made another perfectly-judged sailing decision: the wind died as we got up at 0300, the right time to pick up a 2-4 knot tide all the way to Kirkwall. Sadly the wind took the dying brief rather seriously and instead of a sparkling early-morning sail with views of the northern Orkney islands we were treated to a very wet motor through mist and rain with views only of each other, a bowl of porridge and the chart plotter. But there is a certain satisfaction and a sense of being proper cruising yachtsmen to be had from tying up at 0600 just before a blow, going back to bed and then getting up again and cooking a lavish Sunday breakfast, and we milked it for all it was worth when it transpired later that day that Stephen had got his tides wrong and spent a much longer morning motoring against them all the way.

I’d been to Kirkwall before of course, but that was by bus and it is even better by boat. It may be a tiny town but it has a perfectly proportioned tiny cathedral to overlook the tiny townscape from the sea, and proper docks in the town not shunted off to one side. It is even more picturesque than Lerwick whilst having the same number of branches of Tesco, Boots and Superdrug and at least five times the number of cafes, restaurants, pubs and hotels. Rather than living life on the edge it feels like living life in a small town a long way from anywhere, although this is overlooking the reality that it takes a few hours to get to the mainland and then you are still five hours from the nearest city, unless of course you cough up and fly, but it sounds as if most people don’t bother and are happy to stay put. This last fact is derived entirely from a conversation with the man who cut my hair, but he’d moved here from Norfolk so I treated him as a reliable and vaguely independent source, along with his assertion that more people were moving to Orkney than ever before, and that it had the strongest pro-remain vote in the independence referendum.

Unlike most small towns Kirkwall is bustling even when it rains, which was handy for our visit as it did. We managed to see most of the sights in one day, something that I struggled to fill an hour with in Lerwick, so were delighted to see that we had stumbled upon the St Magnus International Festival and that we had the opportunity to see a top professional choir perform some particularly eclectic contemporary choral music in the cathedral the next evening. Or at least one of us was, and I am very grateful to Tim for putting up with me; he could have foreseen the weather and the travel faff when signing up for this leg, but probably not an evening with Philip Glass.

It was only an hour long (a truly excellent hour in my opinion, I daren’t ask Tim’s) and we were the only members of the audience to make such a swift beeline for the chip shop afterwards for – at last! – my first decent fish supper since Tobermory. Not the only attendees though: we were joined in short order by the entire choir who assured us that they were lining their stomachs en route to the pub. That’ll be a proper choir then.

Two more days of gales and driving rain meant that we had to look further afield for entertainment. On one day we split: Tim to acquaint himself with most of Orkney’s bus routes by visiting the neolithic attractions I’d visited before by bike, and me to do a range of boat and domestic tasks including a trip to the barber’s and the laundry. On the other day we played a blinder by spotting an indoor activity in the form of the Scapa Flow Museum. We’d hoped to sail into Scapa Flow to visit it but in a gale this would have brought with it the possibility of adding another wreck to its already famous collection, so we left the boat and took a bus and a ferry. This was in itself challenging in such wind and rain, but the wettest we got was between the boat and the bus stop. The museum was excellent, covering its role in both World Wars, the scuttling of the German fleet in WW1, the sinking of the Royal Oak by a U-boat and the subsequent building of the Churchill Barriers in WW2, along with much else.

A much-reduced selection of good facts:

(1) Lord Kitchener was drowned off Stromness aboard HMS Hampshire which hit a mine having just left Scapa Flow for Russia to conduct miltary talks in 1915;

(2) the German Fleet had been ‘temporarily interned’, not surrendered, in advance of the Armistice negotiations in 1919; in spite of this the British had been typically beastly to the Germans and not allowed them to go ashore or even fly their flags or go to the dentist for six months, leading them to conclude that the armistice would be harsh on them and they could get their retaliation in first by sinking such valuable assets;

(3) during WW2 the shore-based population at Scapa Flow and around added 100,000 people to the local population of 20,000; all of them had left within ten years leaving behind a mass of concrete pillboxes and the like;

(4) it is very hard to staff a decent museum cafe on an island as remote as Hoy, although the staff were very excited about serving Sir Chris Hoy, who is not related to the island in any way but apparently gets invited to open pretty much anything, including the museum and the local bike shelter, and to his credit seems to agree.

Finally the wind died down and the sun came out, so we left Kirkwall straight away and enjoyed our only light wind/downwind leg of the trip. We managed to get the tide mainly right, gybed inside some Poles (Eastern Europeans, not navigation marks), carried the spinnaker to the Pass of Copinsay and headed up into East Weddell Sound off one of the Churchill barriers in time for supper on board.

Since we couldn’t sail into Scapa Flow we did the next best thing and anchored about 100 yards from it in one of the sounds that had been blocked off first by sinking old merchant ships (‘blockships’) and then by inviting a few thousand Italians to spend the rest of the war helping Balfour Beatty drop a quarter of a million tons of concrete blocks into various very tidal gaps between islands to make what’s now called The Churchill Barriers. Apparently they got around the Geneva Convention (which forbids using POWs on defensive projects) by claiming that they were building a causeway for a road linking South Ronaldsay and Burray with the mainland: this sleight of hand then came true when after the war they built a road on top of it and these hitherto remote islands became a sort of suburb of Kirkwall, characterised by the most authentic rush hour I’d seen since Liverpool.

In order to maximise the near-Scapa-Flow experience we anchored as close as I dared to one of the blockships, this one rather sadly still named as the SS Reginald.

Wriggling around the rocks and the rusty hulks was challenging enough with a modern chartplotter on a sunny day; doing it in a U-Boat at night with a compass and a slide rule must have been a bit harder, and it was interesting to note that in spite of the great loss of life he had caused, none of the local information boards, the museum, or apparently Winston Churchill himself had anything but respect for Gunther Prien the Commander who sneaked in through the blockships and nets, sank the Royal Oak just off Tesco’s and sneaked out again the same way. So much so that you can still buy postcards with his route in and out amongst pictures of battleships and highland cattle.

Visiting the Italian Chapel on Lamb Holm is something most visitors and every cruise ship passenger does on their Orkney holiday. Not many walk there having landed their dinghy on the beach in the next sound, so we felt very superior and the woman in the ticket office did us a favour by identifying the ten minute gap before the next tour arrived. I’m glad we went: it is even more impressive than we expected. I hadn’t appreciated that the POWs who built it were skilled craftsmen and artists in civilian life which explains how they managed to do such a good job, albeit with limited materials. Touchingly a BBC programme managed to reach the lead artist, Domenico Chiocchetti, who was invited back in the 1950s to restore and finish his work, where he gave a lovely speech donating the chapel to the people of Orkney in gratitude for being so hospitable. All I could imagine is that unlike the Roman soldiers on Hadrian’s Wall he must have brought some warmer underwear with him. Unlikely since they were mainly taken prisoner in North Africa.

Apparently walking the entire length of the Churchill Barriers is not a usual thing, judging by the total absence of pavements combined with a tendency among the locals to treat each barrier as a speed trial. It was a thing for Tim, however, and I was more than happy to join in on a sunny and yet again windy day.

We walked all the way up to St Mary’s and back to the boat; then all the way to the big village on South Ronaldsay which goes by the most un-Scottish name of St Margaret’s Hope, without being run over and only once hooted at.

St Margaret’s is not only chocolate box pretty it also has a great pub which owns its own scallop boats, so we took full advantage before trying out one of Orkney’s best features: we’d been told that you could stand anywhere on an Orkney bus route and flag a bus down, and were keen to try this trick out before Tim needed it in earnest next morning to get to the airport while I sailed on to Wick. Luckily it worked, avoiding a two hour walk back, and again the next morning, although by now it was pouring with rain. I did actually feel bad leaving Tim on a beach in full oilskins with his belongings wrapped up in plastic bags, wondering if the bus would stop, but I’m afraid I couldn’t help laughing at the sight and so will you.

The bus did stop, and I got my punishment immediately. I went to pull up the anchor and it was absolutely jammed fast, presumably under some piece of Churchillian wreckage. Only the night before I had set a tripping line amid much discussion about how we could use it to pull the anchor out the other way if necessary; I tried this, I tried motoring backwards and forwards at full speed, then round and round in circles. Nothing. It wouldn’t budge. I was going to have to mark the chain with a buoy and leave it there or I would miss the tide and get caught in the big afternoon wind.

Then a miracle happened, which I can only attribute to the Madonna of the Olives in the Italian Chapel: there was only one small fishing boat in the bay, and its owner had arrived just as I started this shenanigans. He waved cheerily as he motored past and I waved back frantically, not to ask for his help (he was at work) but to apologise for further cluttering up his bay, tell him my buoy plan and that if he could get the anchor up with some help from his neighbours it was theirs. “Nae bother,” he replied, “you don’t want to be leaving it. I’ll pull it out for ye.” He grabbed the chain and I worried it was going to be his back he pulled out as he yanked and heaved. He towed the chain away: nothing. He wrapped the tripping line on a winch: nothing. Then, to my horror, he put his engine in full ahead and tried motoring off. The tripping line (a very cheap piece of rope) hummed like a telegraph wire and then he leaped forward towards the blockship. “That’s you!” he called nonchalantly with my favourite Scottish phrase, and it was indeed me. I hauled the anchor in and wished him the best day’s fishing he had ever had. “Och, that’s fine of you,” he replied, “it’s nothing. You have a good trip now.” Which seemed like a perfectly fitting way to end my visit to Orkney, and cemented its position in my Top Ten bits of the UK coast.

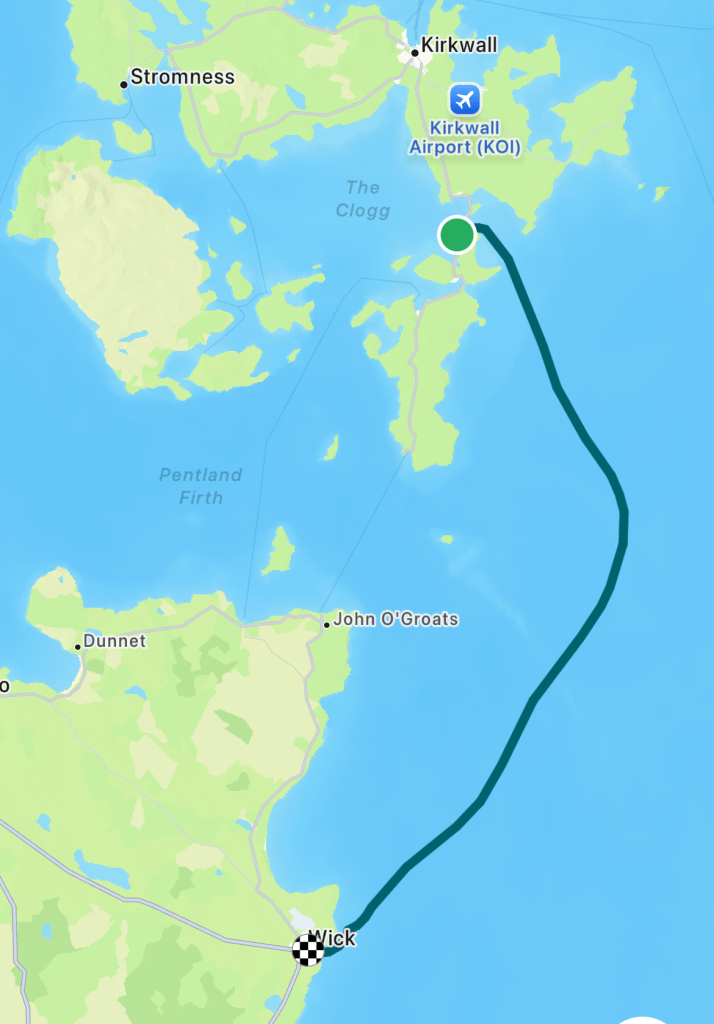

Five hours and a few Hail Marys later I have got my breath back as well as the anchor and I am arriving in Wick having avoided being sucked into the Pentland Firth, onto any skerries or stacks, or under any ferries. I have been here before (Over the top) and although it’s windier today I am well out of the nasty bits having not started from within Scapa Flow. As I pass Duncansby Head I realise that I am now properly on the mainland East Coast: I regret that there is no going back now but at the same time it feels familiar being the North Sea – a ridiculous notion given that I am still many hundred miles from home.

I make it into the harbour just before the big wind arrives; the harbourmaster makes his usual point of coming down to take my lines and having a chat. I mention that, coming from the Northern Isles, this is the hottest I have been for months, and how odd it feels to be saying that in the second most northerly port on the mainland. “Aye,” he agrees, “it can be a wee bit chilly up there.”

I’m writing this sitting on the train, now approaching the searing heat of London, surrounded by Scots who, eight hours into the journey, are now very cheerful and very excited about their festival/gig/stag party/family weekend. My neighbour and I might be the only sober ones aboard. She apologises, she can’t help noticing the pictures on my computer. Have I been sailing around Shetland? She lived in Lerwick for two years and on Bressay for five, now lives in Inverness and is off to spend the weekend with her friends who sailed around the UK last year. She asks about how I found it, and I mention how different Shetland and Orkney are. Ah yes, she says, the worst thing you can do is assume that they are in any way similar, but if there’s one thing guaranteed to annoy a Shetlander more than lumping them in with the Orcadians it’s making any kind of comparison between them.

I stand suitably admonished, but I suspect I know why the Shetlanders are so touchy. That said, I also have to admit that they occupy the most unusual, unique place in the whole of the UK: it’s all going to feel increasingly familiar from here on home.

Leave a reply to phwatisyernam Cancel reply