I don’t know why I say ‘surprised’, I knew very little about Shetland before coming here, and don’t know a lot more now. I knew there were no trees; that it barely gets dark in summer; that it is closer to Norway than Edinburgh let alone London; and I’m sure I read somewhere that Dougie Henshall had annoyed the locals by letting slip that he didn’t like Shetland much in spite of becoming famous on the back of the TV series, although in his defence and mine I can’t find any proof of that.

I also had some terrible misconceptions, and some obvious gaps in expectation which I really should have spotted because they are – well – obvious. The most notable of these is that it really is very cold: I have occasonally looked at weather forecasts over the last couple of years and tried to process and log the fact that it is consistently 10-15 degrees colder here than in London, but the consequences simply hadn’t sunk in. They have now: it’s been in the high twenties for weeks at home; here it has only once gone above 12 degrees (it was 16, and people actually remarked to me on how warm it was). This makes appreciating the wild scenery quite a challenge: trying to sit in the cockpit, or outside a welcoming Boating Club (no sailing clubs here – they all row and fish as well as sail), with a drink is simply impossible unless you’re wearing a fleece and gloves. The other night it was three degrees centigrade overnight. In mid June. I am now dreaming of Essex in September.

My worst misconception, obvious only now I have been, is that Shetland was somewhow bigger, more populated, more prosperous and more recognisably modern than Orkney. I assumed that compared with tin-pot Kirkwall, Lerwick would be a major conurbation with all the High Street shops you’d expect to find in, say, Kidderminster. How ridiculous. Lerwick is indeed quite a big town by island standards but it is smaller than Kirkwall (7,000 inhabitants to Kirkwall’s 10,000) and it is the least towny town of all the untowny towns I’ve visited, being essentially a fishing village onto which has been bolted variously some smallish docks, then a Victorian civic centre and finally a lot of oil rig and windfarm support businesses, and for a few hours each day in season (I note they try not to use the word ‘summer’ here, quite sensibly) a thousand or more bewildered cruise ship passengers who wander around in ponchos clutching soggy maps, many of them apparently on the verge of tears. It does, however, have the brilliant postcode of ZE1.

The rest of Shetland, and there is an awful lot of it, is more or less totally barren. Lovely to look at, especially from the sea, with extraordinary cliffs and sea stacks and wild shores, but not the kind of place where you’re likely to bump into anyone. Or, for that matter, find a road to where you want to go. There are tiny hamlets which call themselves villages, and tiny sheep farms and crofts strung out down rutted tracks, and that it is pretty much it, except for anywhere you might bring oil or wind farm supplies ashore, when suddenly there is a smart new normal road with a lane in each direction.

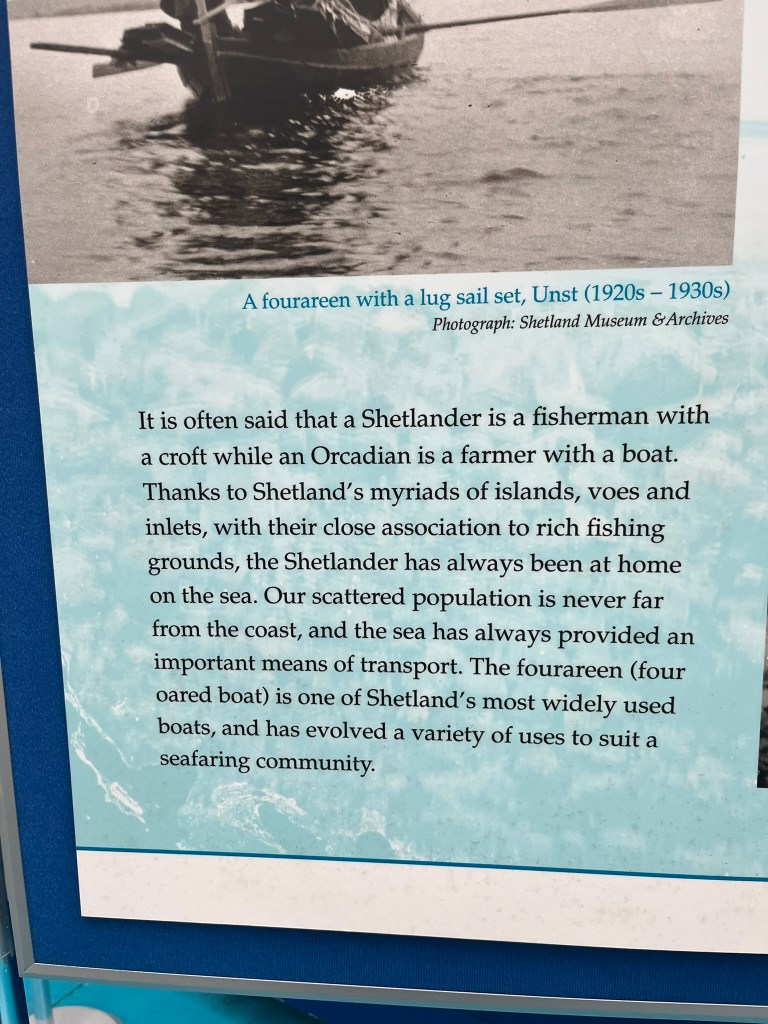

It makes Orkney look like Metroland. Indeed, I rather liked this non-judgemental comparison in the Unst Boat Haven:

Not to say I haven’t enjoyed visiting, but I am glad we never came here for a two week family holiday. Some people seem to but they must have a very different idea of parenting, and children who aren’t scared in a tent in the garden. (Full confession: I didn’t like it either, there seemed to be a lot of animals doing things in the bushes).

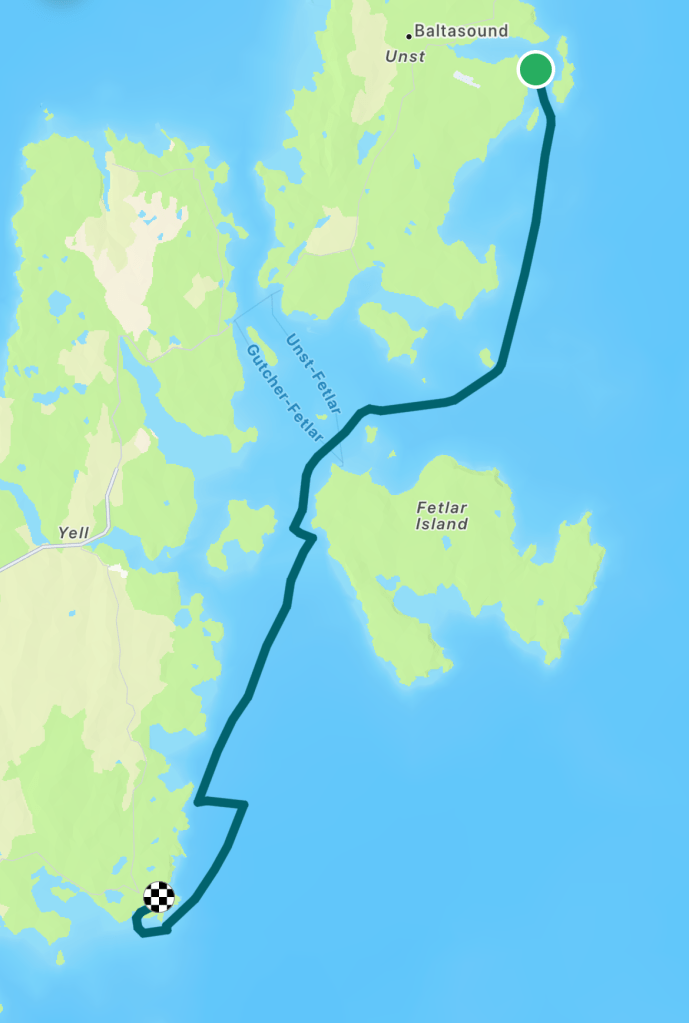

The weather is also even more ridculous than I had anticipated: never mind the cold, which is at least predictable, the wind and the rain seem to have no connection with reality and do what they want when they want. I was first alerted to this possibility when I noticed that unlike every other Inshore Waters forecast region in the UK which has a 24 hour forecast and a 24 hour outlook, Shetland has 12 hours for each. In other words, tomorrow is an outlook, and a pretty random one at that, as evidenced by my trip around Muckle Flugga and indeed every other day sailing. It’s also quite windy most of the time, even when it says it won’t be, so although I allowed two weeks to explore Shetland I will probably only have sailed about half of those days, and I have been beating South ever since beating North to round Muckle Flugga. Perhaps that’s why you need the two week family holiday.

The sailing is spendid, however, and given a month and an insatiable desire for anchoring in totally deserted places whilst eating mainly long life food, you could have two weeks of cracking sailing and another two of looking at cliffs and birds while sheltering from the wind. I’ve sailed past bays where in ten miles there are as many secure anchorages tucked away behind cliffs and headlands, so there are whole chapters of the pilot book I’ve barely opened.

Although everyone says Shetlanders are keen sailors, I didn’t see another yacht the whole time I was at sea, and nobody expected me to. Even just sailing around the coast is never boring though as there are cliffs of every size, shape and even colour with all sorts of weird offshore rocks that tourists are encouraged to drive or cycle or walk hours to gawp at.

If ever boredom does set in on a long coastal passage, you can always amuse yourself by looking at the map and trying to keep a straight face. On the island of Fetlar alone you will find village/hamlets called Houbie, Tiptoby, and Muckle Wirawil. Fetlar’s hills are called The Heog and Lamb Hoga, Mavis Grind, Haggrister and The Roonies. I wonder if the ancient Norsemen didn’t have a cracking sense of humour.

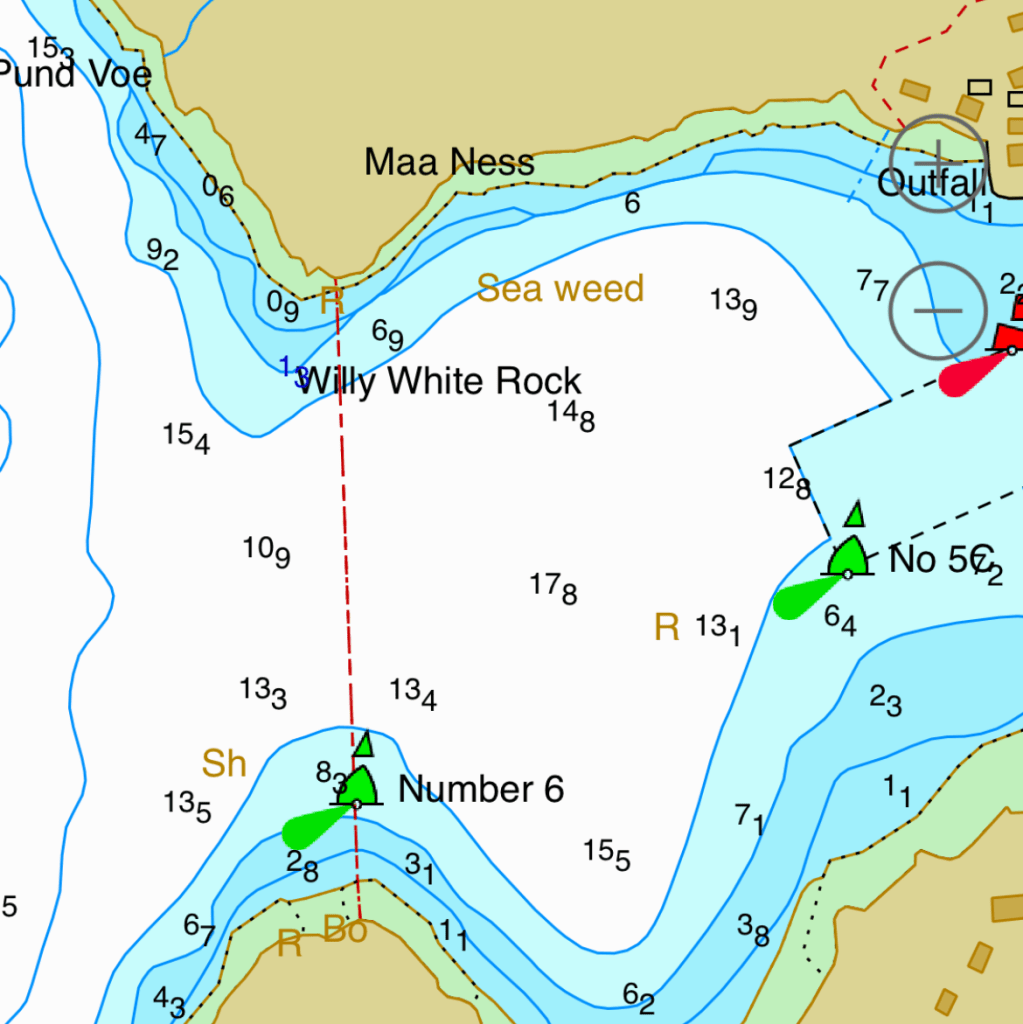

The charts are the same – although it is quite dangerous in the wrong conditions, how can you take this rock seriously?

We don’t have rocks at home called Billy Black Rock or Freddy Fastnet, for good reason.

Scattered around this wilderness I found the friendliest people and some interesting spots to explore. I very much enjoyed the aforementioned Unst Boat Haven, which is like a small barn with traditional boats in it, including rather unexpectedly a scale model of a Thames Barge made out of matchsticks. Very annoyingly I forgot to take a picture. Everything else was very Shetland-specific though, with a range of traditional fishing and cargo-carrying boats that were quite common until recently. They all shared a very distinctive shape clearly derived from longships and Scandinavian designs.

What I hadn’t appreciated was that without any trees (at all, there really aren’t any and unlike anywhere else in Scotland, never were) the Shetlanders only built boats with wood imported from Norway. Presumably they came with plans, like an Airfix kit, so the boats all look Norwegian. Except for this very 20th-century folding boat marketed would you believe by Berthon before they got into super-yachts:

Even that has a bit of a Viking-looking stern-post.

The Viking feel of the whole place extended to this rather fine longship replica which made a good backdrop to the anchorage off the hamlet of Haroldswick:

I spent a night in Baltasound, which proudly calls itself the capital of Unst and boasts the most northerly post office and school in the UK. It appears to have about 20 houses and a small pier, but it used to be the northenmost herring port in the UK with a seasonal population of over 10,000 living in bunkhouses, many of them ‘Gutter Lasses’, women from the islands for whom 14-hour days gutting and packing herring was the best-paid, if not the only, job available. An excuse for this brilliant picture from the Boat Haven, all of them named:

I also spent a couple of days sheltering in Burravoe on Yell, a bit further south (it’s all relative). This had two great sights: the first, a shower block made out of an upside-down lifeboat from the SS Canberra:

Second, a tiny but lovely museum called The Old Haa which had exhibits about both the exciting things that have ever happened on Yell: a Catalina flying boat which crashed on its way to find the Tirpitz in 1941 and, more movingly, a German sail training ship whose captain had read his almanac wrong in a storm in 1927, thought he had spotted the light of Fair Isle lighthouse 60 miles south, headed up and found himself and a ship of 35 cadets being driven into a rocky bay. Both exhibits had detailed and respectful biographies of the victims and heart-warming stories of crofters running many miles across their local wilderness to drag the few survivors out of the wreckages back to safety, and of the survivors and their children and grandchildren making pilgrimages back years later to thank them and their children and grandchildren. I loved that the locals found the ship’s figurehead years later and erected it as a memorial to the drowned cadets, overlooking the bay in the middle of nowhere, and they still head out every year to paint it. I had hiked along the cliffs through miles of wilderness and could see it in the distance, and found the story very indicative of how seriously you take life when you live this far away from everywhere else.

A few things were as expected. The ponies are every bit as tiny as the ones you see in posh paddocks in Surrey…

…and in many places you could be forgiven for thinking you were in Norway not Scotland:

Scalloway in particular felt very close to Norway, emotionally as well as geographically, and they were keen to celebrate the Shetland Bus operation in WWII when countless Norwegian sailors ferried supplies and people to and from the Norwegian resistance:

The very Scaninavian-looking red building is actually called The Norway House as it’s where most of the sailors lived; the slip is called the Olav Slip after the Crown Prince who opened it.

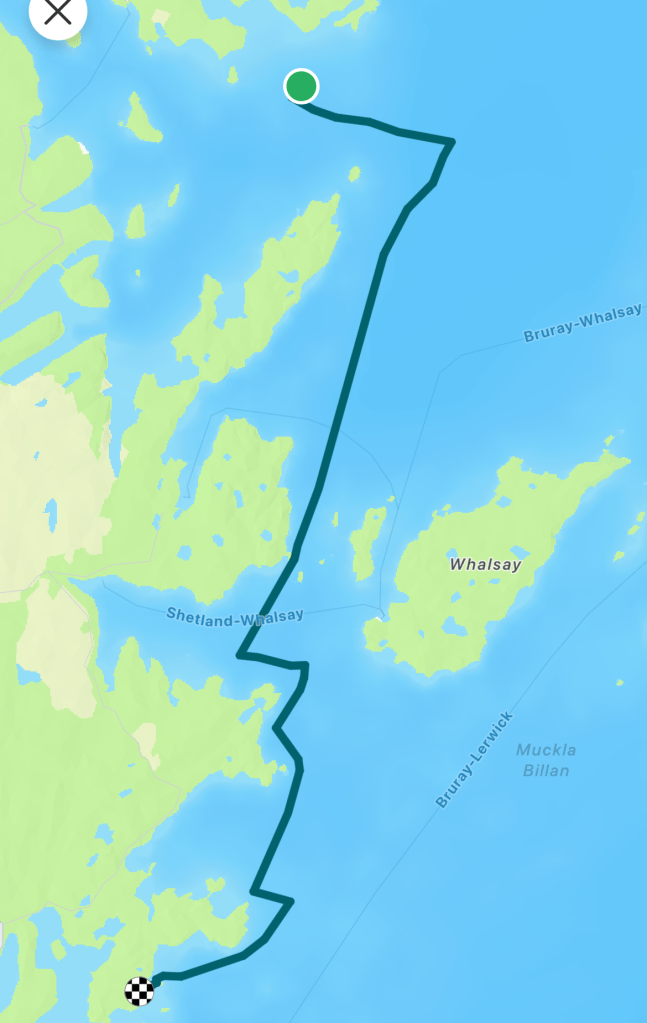

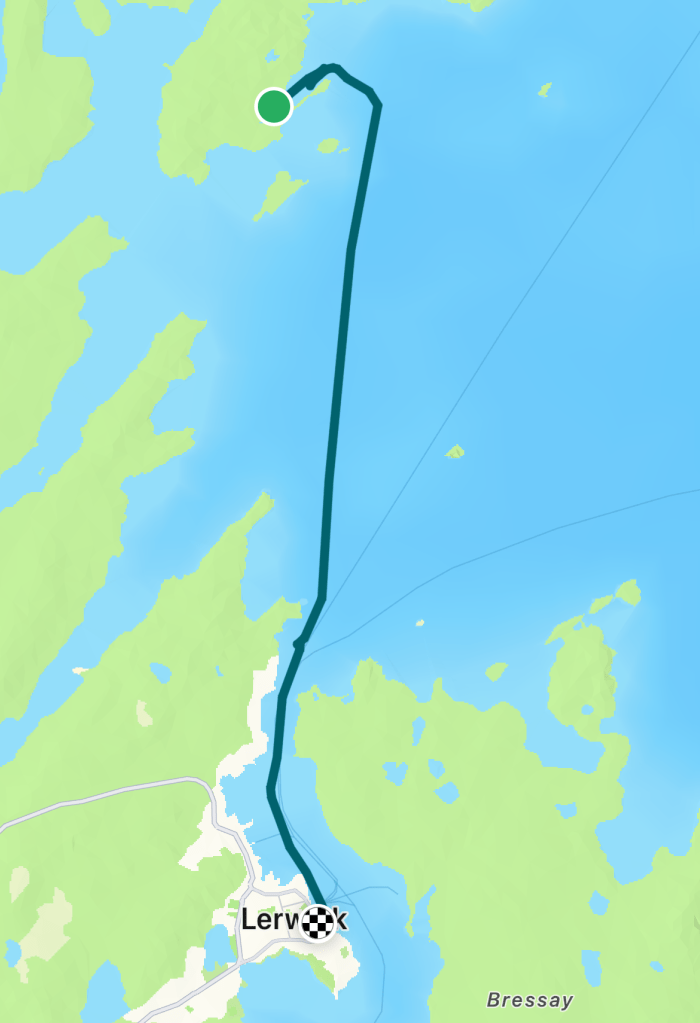

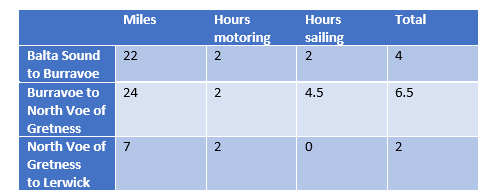

Eventually I made it back South to Lerwick, via the excellently named anchorage of North Voe of Gletness, with a final morning motoring through thick fog. This would be terrifying and irresponsible on the South Coast but here I was the only vessel on the AIS screen, and when miraculously the fog lifted as I called the Harbourmaster he reassured me that I was the only boat moving that morning and could go where I liked.

Lerwick looks entirely Scottish but all the boats around me are Norwegian, plus the French penguin-spotters who excitedly told me they had added otters to their spotting list. So have I, several times, but I didn’t spoil their excitement.

I do wonder how many of the cruise ship passengers have watched all the series of Shetland though, as that seems to be the town’s main draw. Astonshigly, the big elegant Victorian house which I assumed they had dressed up to be the police station in the series is actually the police station:

Even more astonshingly, for true fans of the series who were disappointed by the ridiculous accent of Sandy the sergeant, I find that it is actually a real Shetland accent and I am forever doing a double-take when I hear someone speaking with it (not everyone, but not uncommon). Hurrah for the internet, which tells me “the character Sandy Wilson, played by Steven Robertson, has an authentic Shetland accent. Robertson himself was born and raised in Shetland, making his portrayal of Sandy Wilson’s accent genuinely representative of the local dialect. The Shetland accent is a unique blend of Old Scots and Norn, an extinct North Germanic language, which gives it a distinct flavor different from other Scottish dialects“. Apparently it is the hardest in the world to copy, according to the Daily Record.

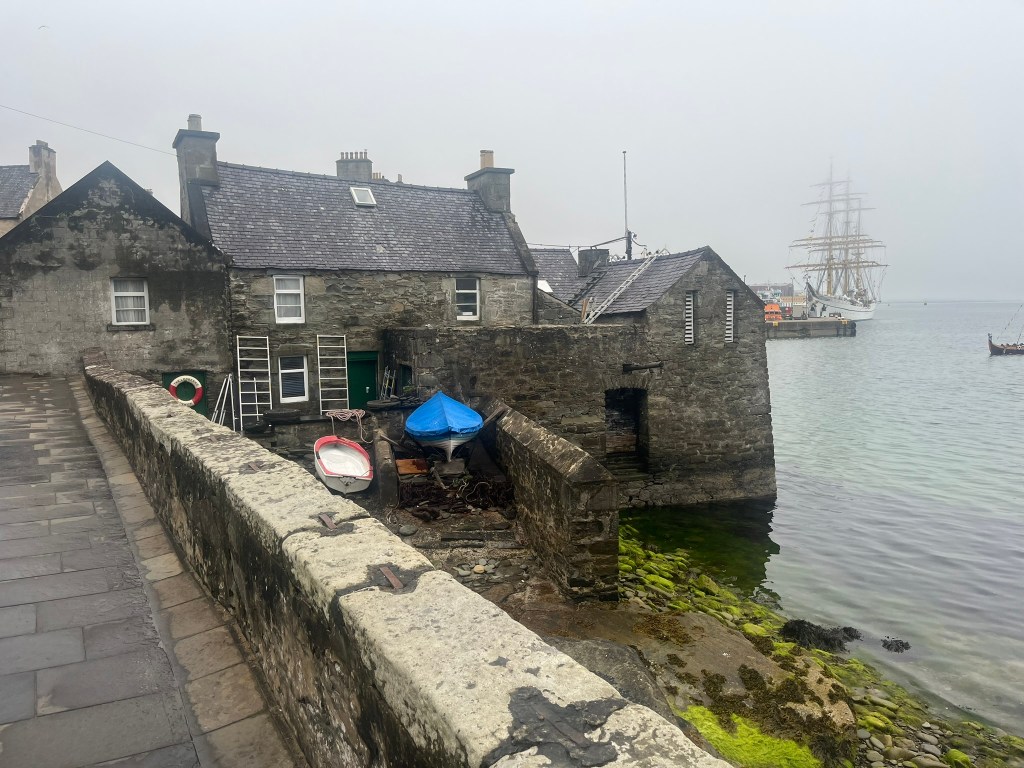

Sadly the house they used as Jimmy Perez’ is in rather a state:

Apparently the new owners don’t like the publicity, which is unfortunate since it appears in absolutely every guidebook and Tripadvisor-esque website, to the extent that they made the council take away the Hollywood-style star they had proudly put in the pavement outside.

You’ll notice the very authentic-looking sailing ship in the background. This is the completely authentic German sail training ship Gorch Fock, with a rather more competent Captain than the sad one wrecked on Yell as they have made it to Lerwick in one piece, and in addition to the cruise passengers there are a hundred or so German teenagers looking in vain for a good time in downtown Lerwick. Not entirely competent though – he’d left the 40-foot bowsprit overhanging the entrance to the Small Boat Harbour where I had been directed by the Harbourmaster. My heart was in my mouth when I realised I could only just squeeze my mast past the end of it without ramming the dock wall opposite: just to make it more fun there were a dozen sea cadets doing something impressive on the bowsprit, and I’m not sure who was the more nervous.

I tied up next to some friendly Norwegians who had been watching my progress with a degree of concern and applauded my eye-of-needle boat-threading skills. Later that afternoon we watched as dozens of cadets slowly manhandled the 266-foot ship back a bit down the quay.

Leave a reply to peterdann11 Cancel reply