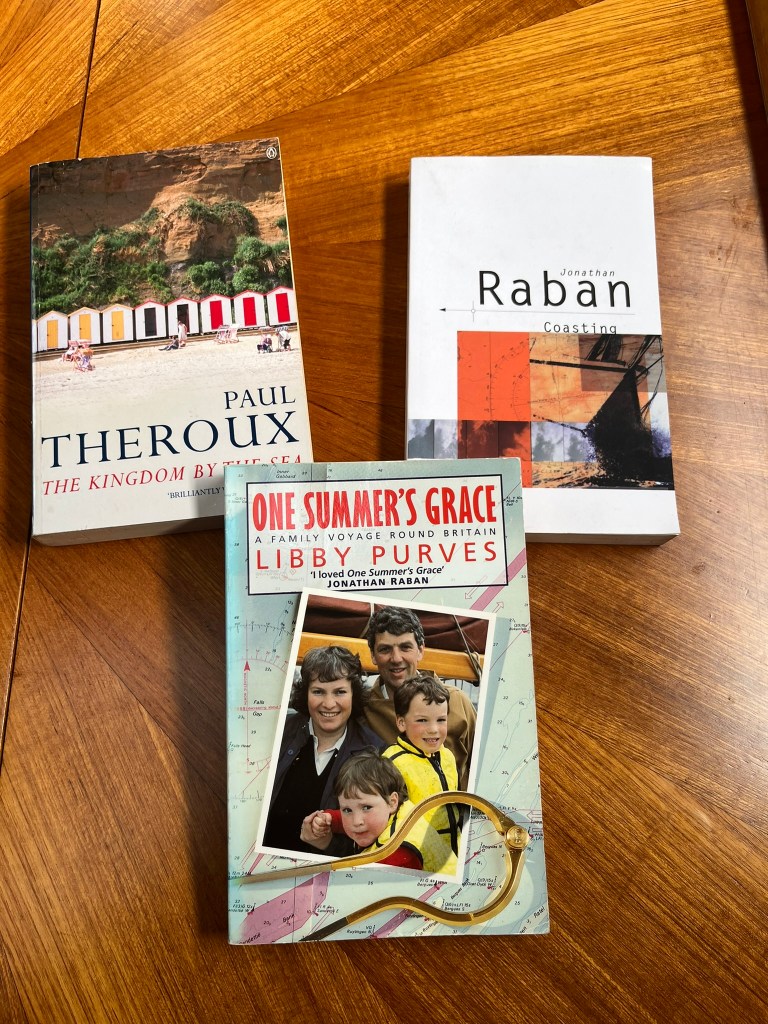

To the non-sailor the name Libby Purves, if it means anything at all, will mean the erstwhile presenter of such legendary Radio 4 programmes as Midweek; they may even remember her on the Today programme with Brian Redhead. Cruising sailors will probably know much more interesting things: that she is married to Paul Heiney (yes, him off That’s Life!), that they are both mad keen sailors, that she writes a column for Yachting Monthly as well as The Times, that she has won even more awards than my blog, and they may also know, or even have read, her book about sailing around the UK with their two small children: One Summer’s Grace. Whilst not quite in the same literary league as Paul Theroux or Jonathan Raban it is nonetheless very readable and never descends into twee family stuff.

I have all three on my bookshelf in the saloon, and it is One Summer’s Grace that has provided the most memorable scene for this trip: of the time when, after a week or two of filthy Scottish weather heading up towards Cape Wrath, they come across a fishing port still under construction where they are welcomed in to the Mission to Seamen and offered showers and hot food in the fishermen’s cafeteria.

The village in question, miles from anywhere, and only about 15 miles south of Cape Wrath, is called Kinlochbervie, and the name stuck with me, and indeed the whole episode, suggesting as it did that if I were to follow in her footsteps I would have to endure weeks of wet and cold misery interspersed – hopefully – with warm hospitality from rough working locals at the ends of the earth. It would be worth visiting Kinlochbervie just to have some of that experience, and so it became one of my landmark unlikely destinations along with Scrabster, Sunderland and Spurn Head.

It was, therefore, quite a shock when I mentioned this to my friend and regular blog commenter Jamie (I think that’s the right word for someone who adds comments to a blog, as opposed to a commentator who would be critiquing it, and I don’t want to encourage that), who said “that’s where my mum lives. We should meet up there.” Plans were made, and slowly I began revising my expectations of casting myself on the mercy of fishing folk to arriving somewhere where I actually sort of knew someone, which made it even more of a destination.

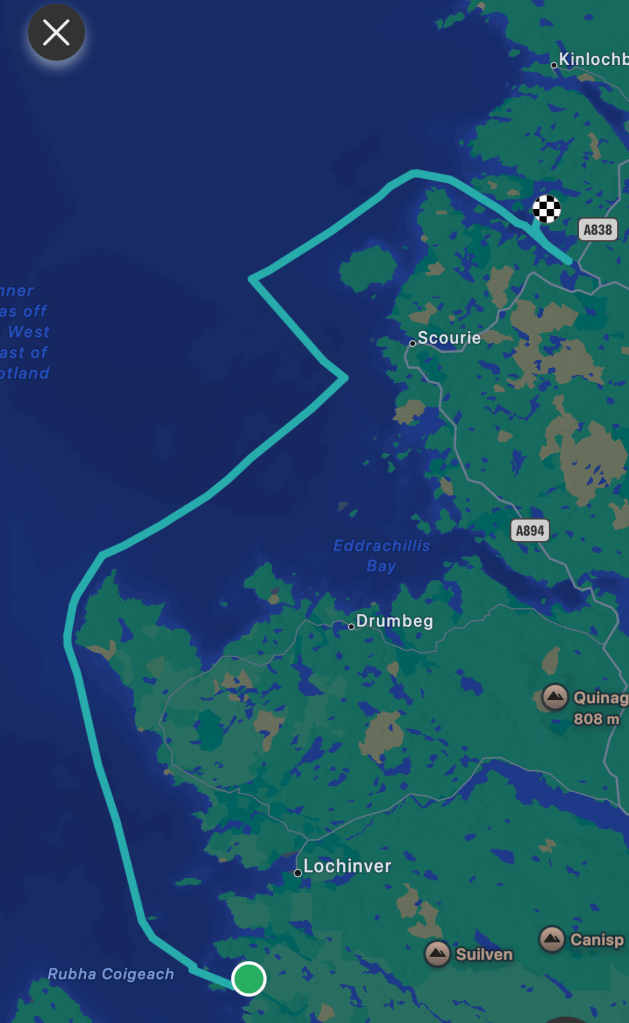

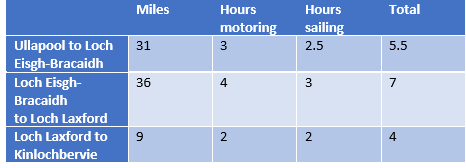

First I had to get there, and whilst it’s only a long day’s sail from Ullapool I didn’t want to hurry as I had deliberately left some lochs unexplored in my otherwise intensive touristing around the Sutherland coast last year. There was also the possibility of climbing one more mountain from Ullapool before I left, which I was really looking forward to. Sadly, yet again the weather intervened: the forecast for the weekend was beginning to look rather nasty with the end of the balmy weather and more typically Scottish conditions: up to 40 knot gales, 10 degrees and driving rain for days on end. If I was going to see any lochs and get to Kinlochbervie without being dashed to bits on some rocks I had better leave now, even though the same weather forecast promised I would be motoring into a flat calm for two days.

Isn’t it funny how weather forecasts are strangely accurate when forecasting bad weather, but always get it wrong when promising something good? No sooner had I poked my nose out of Ullapool harbour than the wind piped up so that I found myself motoring into 20 knots.

I pressed on, thinking that once I got to the corner I would be able to hoist sails and bear away for a fun sail, Not a bit: as soon as I got to any turning point the wind followed me around as it always does. I was bored with motoring now so put the sails up anyway and spent the whole afternoon beating into a steady 20 knots: with the tide under me it was creating some nasty waves and the foredeck was regularly wet. I was reminded how much more fun beating is when there are two or three of you, and after a few hours I was quite tired of steering, winching, reefing, tacking and tacking again. Finally I was round the remarkable Old Man of Stoer…

…and could bear away onto a fast reach to my chosen deserted loch. Cheerful at last I went below to put the kettle on and my cheerfulness evaporated instantly: I had forgotten to close the forehatch completely and all the bunk cushions I usually sleep on were soaking wet. It was at least still very warm so I threaded my way through the rocks to the excellently-named Loch An Eisg-Bracaidh (I had chosen it for the name) and instead of relaxing looking at the wonderful scenery spent the evening hanging cushions and bedding out in the sunshine, now grateful for the strong breeze that was still blowing.

I made a few tweaks to my strategy the next day and it was considerably better as a result. First, I left early so that I was sailing into 12 knots rather than 20; second, I put up with a bit of tide against me for the sake of smaller waves and third, I remembered to shut all the hatches quite firmly. Having taken steps one and two this wasn’t so necessary, but it made me feel better and I had a rather more enjoyable day as a result. Still warm and sunny, beating into any kind of northerly feels a bit chillier than you’d hope, but this time I arrived at an even more deserted loch in the early afternoon so I could enjoy the last day of sunshine and finish drying the cushions.

Loch Laxford doesn’t sound particularly Scottish but it is brilliant to look at and totally deserted except for a couple of fish farms whose workboats went home in the afternoon and left me as the only person for miles around, or so I thought. I had found a small bay to anchor in which sheltered me perfectly from the building wind, and went ashore to explore. Over the hill was an outpost of the adventure school started by John Ridgway, the guy who rowed the Atlantic with Chay Blyth, and now run by his daughter, also in the middle of nowhere, but a different nowhere I suppose. I wonder what he thinks of the hundreds of people who now set off each year to row the Atlantic the way people run marathons for charity. I could hear the squeaking of excited children in the far distance (or perhaps they were screaming at the cold water they’d been dunked into) but back down on my side of the hill it was just me, the boat and what sounded like a lot of cuckoos. Luckily they went to bed early and left me to enjoy the silence.

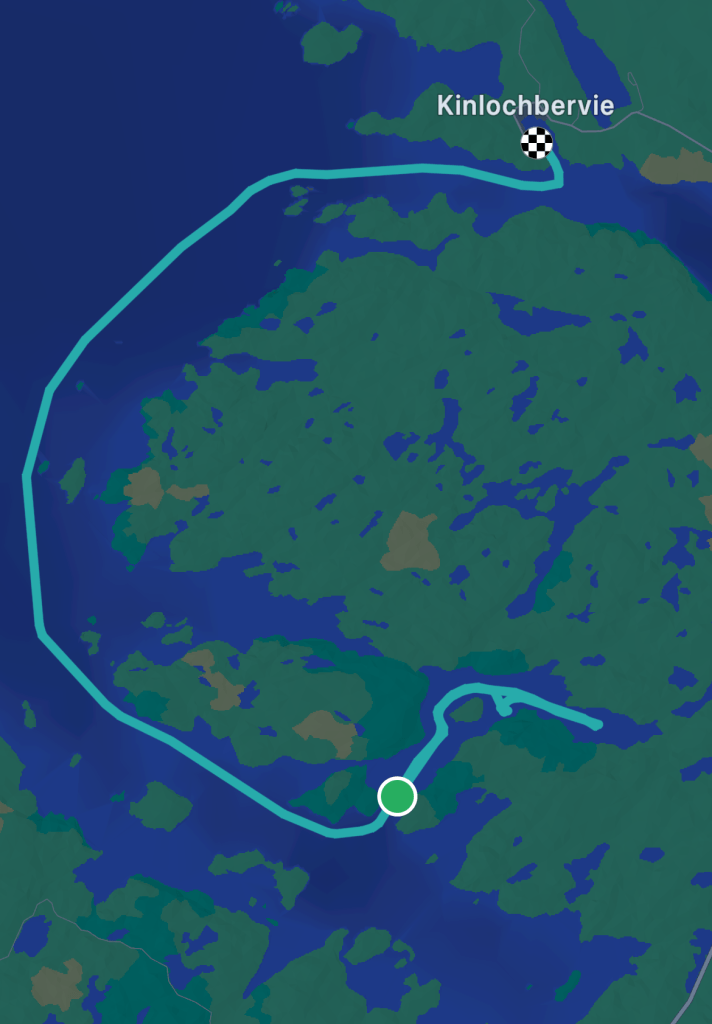

My plan had been to embrace this wilderness by spending a couple of nights in one of the lovely lochs enjoying the balmy weather, but the weekend was now looking even more dire than ever with a promise of freezing cold and pouring rain the next evening followed swiftly by at least three days of gales. Loch Laxford looked perfectly sheltered but the prospect of sitting in the boat watching the rain and the wind didn’t sound as good as sitting in the boat watching the rain and the wind while plugged into the mains and only yards from a shower and a cafe, so the next morning I called the harbourmaster at Kinlochbervie and wondered if I might tie up on his pontoon a few days earlier than planned. It’s very small and fills up quickly in bad weather according to the pilot books, and my concern was confirmed when he said “yes of course but I’ve had three yachts call already this morning, it’s always like this in bad weather.” I really didn’t want to miss out, so instead of spending the evening in the spendidly-named and rather beautiful Loch A’ Chadh-Fi, I motored into it past the Adventure School, anchored, drank a cup of coffee and motored out again.

I’d checked on the AIS that there weren’t hordes of yachts already heading for Kinlochbervie and allowed myself the luxury of a last sail in the sunshine: already there were clouds on the horizon for the first time in weeks.

Quite a lot has changed in Kinlochbervie since the Purves-Heiney family visited in 1989. They finished building the fish warehouse and the new road and then, just in time, got the EU to cough up for a pontoon for a few visiting yachts and a wide range of local creel boats to keep them out of the way of the big boys at the fishy end of the harbour. This is where I was headed, heart in mouth as I rounded the corner in case all the spaces were taken. Completely empty. “Park where you like” said the harbourmaster when I called on the radio, so I did. Rather to my surprise, the fisherman who was clearly very busy unloading his creels stopped what he was doing and came over to take my lines. This is simply unheard of: fishermen invariably ignore yachts except for when they’re trying to run them down, although I have already experienced how much friendlier Scottish fishermen are than their English equivalents. “You’re just in time,” he said, indicating the grey clouds now appearing over the even greyer fish warehouse and ice plant, the smelly staple of every decent West Coast fish harbour. He was right there as well: I had time to have a shower, introduce myself to the harbourmaster and put up my Scottish Summer cockpit tent before the heavens opened and it began to blow. I felt especially smug as a group of very cheerful Americans tied up behind me on a big yacht just in time to get soaked as they tidied everything away.

The good news was that I was now tucked up away from the wind and rain that was going to howl across this part of the world for the next few days; the bad news was that I was in a village devoted almost entirely to fishing. It was even clear that the Seamen’s Mission that had entertained Libby Purves was long gone, to be replaced by two cafes with peculiar opening hours and a Spar shop. I was determined not to bother Jamie’s mum by announcing my early arrival, so settled down to a long weekend of writing the blog, cleaning the boat, doing some maintenance and getting around some serious organ practice.

This was a week ago, and you can tell from the timing of this post that I failed miserably: I managed the cleaning, the mending and the practice but not the blog because there simply seemed to be quite a lot going on.

First, it didn’t actually rain all the time so I got a chance to explore the village a bit and see huge waves crashing onto rocks all around, which always makes you feel better when you are tied onto a sheltered pontoon.

Then it turned out that the Americans, who were on a sort of training/adventure course, were very good at coming up with things to do – just as well as they were paying good money to be stuck in Kinlochbervie for four days in the rain. This included coming round for chats just when I was about to do something interesting, but also blagging a tour of a fishing boat, on which they were given boxes of live crustaceans, including – most improbably – more lobsters than they could eat. They insisted on giving me one and I had the fun of plucking up the courage to improve my crustacean-murdering skills to the extent that I now feel quite heartless having sliced a lobster’s brain in half in the cockpit. Well worth it to have £40-worth of supper for free.

They also dragged me along to an evening singing sea shanties in their saloon. This is the kind of activity I would usually run a mile to avoid, but it was quite hard to hide when moored next door. To make matters worse most of the so-called shanties were either Country or Western numbers with nothing to do with the sea, and there was not a scrap of alcohol on board, it being ‘a training trip’, the skipper explained. I was pressed into performing some properly English numbers, so I found myself singing Spanish Ladies sober for the first and hopefully last time in my life.

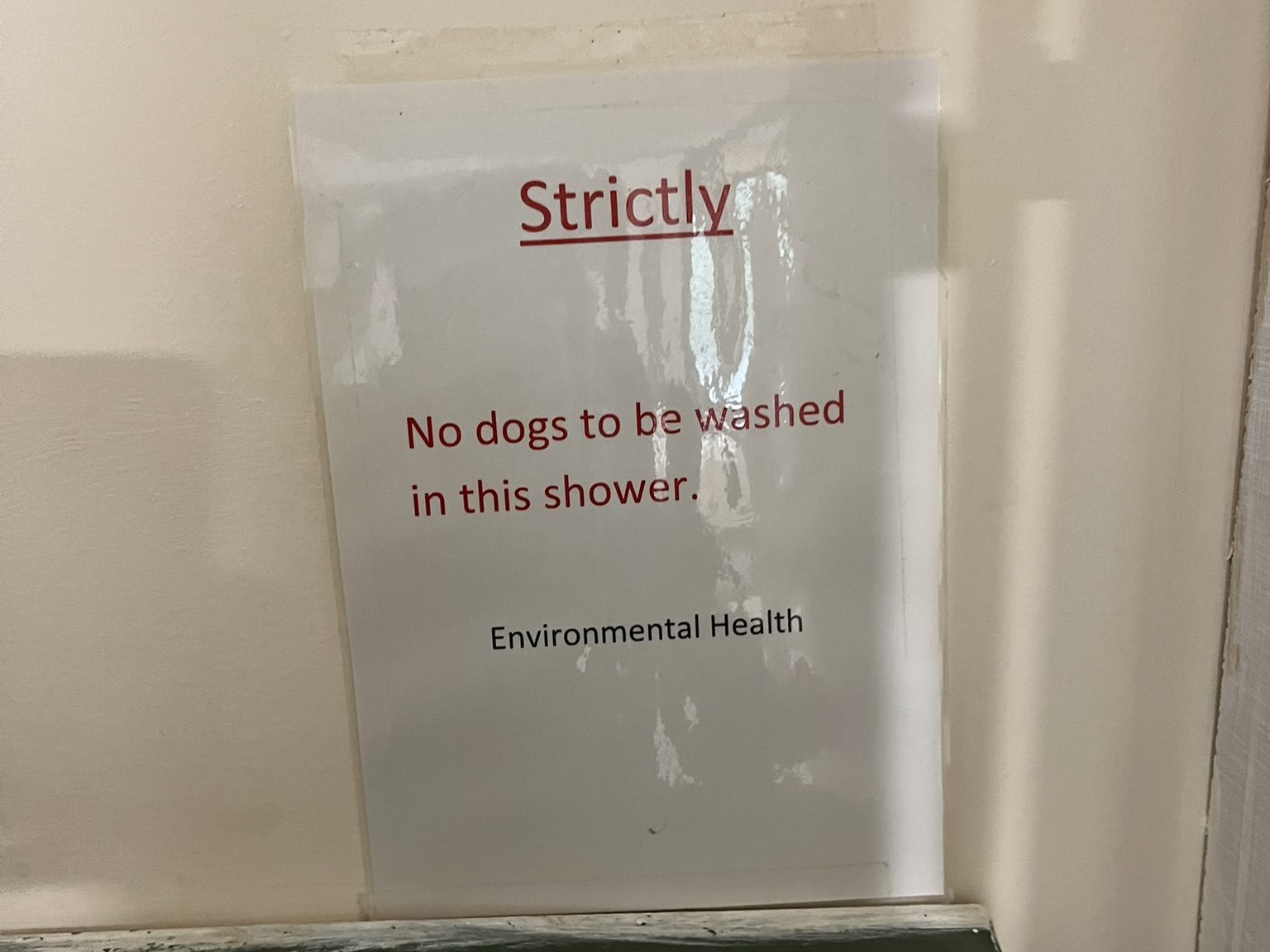

I also made frequent trips to the shower that visiting yachts share with the fishermen in the hope of finding someone in the act of washing their dog in it. Sadly to no avail.

There were still two days left to catch up on blogging when Jamie let the cat out of the bag. He’d seen the forecast and wondered where I was, and I couldn’t very well lie since everyone else in the village knew I was there. So his mum (whose name is Rosalind so I shall stop referring to her as Jamie’s mum from now on because we are no longer students) was alerted, and I was advised that an inspection of the boat was in order.

This turned into an even more fun couple of days than the first two. First, Rosalind drove me to meet her friend Jenny who has started a food truck where we were served fabulous fresh langoustines, with chips that would make The Wolseley jealous, which we ate not in a chilly lay-by but in her nice warm house with views sweeping across the mountains and down to the Point of Stoer.

Then we were joined by her friend Margaret who (amongst, it would appear, many other things) owns a creel boat in the harbour and wanted to see what the inside of a yacht looked like. Tea was served, and in due course the two began a conversation about me. “I think Ben Stack would suit Peter best,” opined Margaret, and Rosalind agreed. “I’ll pick you up at 9.30 then,” she suggested, “on my way to Inverness to pick up Jamie. You can hitch a lift back”. I gathered that I was expected to bring walking boots, and felt that to say anything other than thank you would come across as ungrateful, in spite of the forecast for it to be blowing a near-gale still, with heavy showers all day and a wind chill of 1 degree.

I didn’t die on Ben Stack, although for a little while I did consider that a possible outcome. It was a relatively short but hugely rewarding walk, except for the near-death bit when I lost the path and found myself climbing a vertical wall of moss while freezing rain and a howling gale reduced visibility to a couple of yards and blew away my rucksack cover. But that was soon over and the sun came out for the rest of the walk with another series of stunning views across all the lochs I had sailed past and into since Ullapool, up to Cape Wrath itself.

Back to the main road and I put my thumb out to hitch a lift for the first time in about 45 years. To my astonishment, the first van stopped. I climbed in and to my further astonishment it instantly began to rain incredibly hard. My hosts introduced themselves, clearly excited to have picked up a genuine walker in the actual middle of nowhere. Then, even more astonishingly, it turned out that they came from Chatham and Sheerness respectively. I don’t know who was more disappointed when I told them I was from Hoo.

They dropped me at a crossroads where they turned off, but the sun came out and it was a lovely spot. Less luck hitching this time, as for a quarter of an hour campervans and sports cars on the NC500 passed by ignoring me. Black clouds gathered again as I desperately thumbed at one more campervan. Oops! It was an ambulance, and my arm came quickly down, but too late: it had pulled over. I apologised profusely. “Don’t you worry,” said the incredibly cheerful woman in what you probably don’t call the passenger seat in an emergency vehicle, “we’ve got nothing on. Hop in the back, just don’t lie down on our bed though!”. The final piece of astonishment: the instant I shut the door the heavens opened again and unleashed a rainstom so violent I couldn’t hear the sound of the engine over it. The moment they pulled up at the harbour (they were going to the cafe to get a coffee) the rain stopped.

By now I was exhausted, and reckoned I had pushed my rain-dodging luck to extremes. I collapsed onto a sofa in the boat in the hope of getting a quick forty winks before Rosalind and Jamie were back from the airport.

“Ahoy, Blue Moon!” came a cheery call from the dockside. My rest was going to have to wait – a few more days, as it turns out, but that’s the next post. But I had fulfilled my ambition of casting myself on the mercy of the Kinlochbervie locals and found them even more hospitable than the Purves-Heineys had.

Leave a reply to peterdann11 Cancel reply