I’m walking backwards for Christmas

Across the Irish Sea

I’m walking backwards for Christmas

It’s the only thing for me

I’ve tried walking sideways, and walking to the front

But people just look at me and say it’s a publicity stunt

I’m walking backwards for Christmas

To prove that I love you

I’ve had this incredibly annoying tune on my brain all day now, because that’s what I’ve been doing. Crossing the Irish Sea, not walking backwards. It’s The Goons, of course, and we had it at home as it was on the B side of The Ying Tong song. I really liked the Ying Tong Song, aged about seven I suppose, and it made my Dad cry with laughter, but I always hated I’m walking backwards as it simply wasn’t funny, and wasn’t as silly. Now I hate it even more, and having written about it I suppose it will come back and haunt me in days and years to come. Funny how people don’t even mention The Goons these days; it’s probably just King Charles who digs out his old gramophone and puts on a 78 of one their shows.

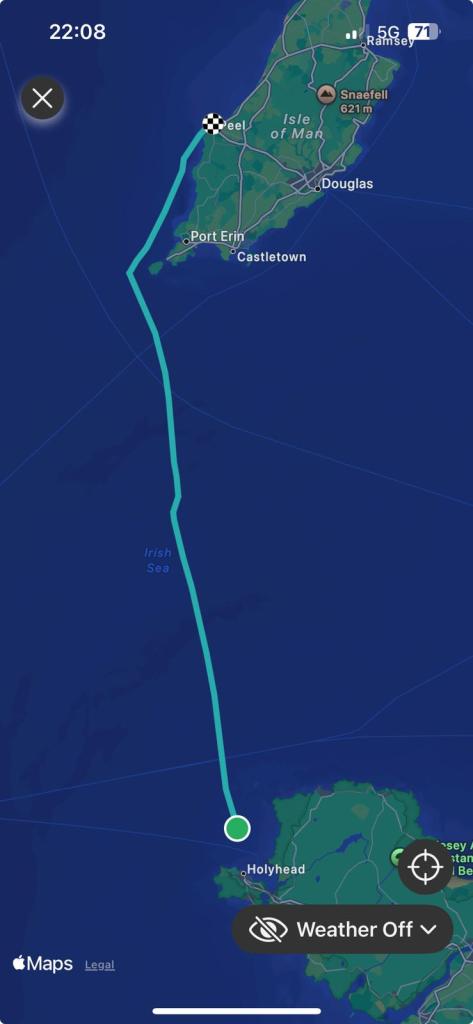

Back to the voyage in hand, and the need to get from one side of the Irish Sea to the other which, if you have been paying the least bit of attention the last two years, you will know generally involves the Isle of Man. And so it did this year, and now I have crossed the Irish Sea not only up or down each of its four sides but also across the middle both horizontally and diagonally, and now vertically too. I have one diagonal left, and since that would involve sailing from Whitehaven to Holyhead, two of my least favourite places on the whole trip, I will have to live without that particular honour.

Although Holyhead is a very sad town, it’s not all bad. The only Tesco on Anglesey for instance, and a railway station with direct trains to Euston sometimes, and a very jolly sailing club. In addition to having a jolly picnic tea on the boat we managed to find a new feather in its cap: the Pet Cemetery. This had been on Charlie’s to-do list since he moved, so we ticked two big boxes in one afternoon. The whole experience was enhanced by one of his support workers not only having been a Holyhead Coastguard but having a dog buried in the cemetery, so Charlie and I got a win each. The only downside was driving past the Coastguard station and having him say, rather mournfully, “I see my ex is on shift this afternoon, that’s her car.” Now every time I hear the Holyhead Coastguard I wonder if it’s his ex I’m listening to, and a whole load of possible romantic sadnesses pass before my eyes. Did love blossom over the thrill of the Mayday and the Navigation Information Broadcasts, but not survive the duller, harsher world of domestic life on Anglesey?

Luckily I won’t have that worry for much longer, because I am now out of her Coastguard area, having set off for the Isle of Man at an unspeakable hour the next morning. An hour made even more unspeakable by Charlie phoning me at 0430 to remind me that I needed to get up to catch the tide. Since telling him that, I had worked out that it was 0530 I needed to get up, which he found a lot funnier than I did.

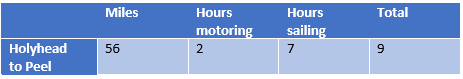

Even an early morning call has a silver lining though, and mine was getting even more favourable tide combined with a wind which miraculously had gone around to the South, meaning that so far I have had the wind behind me on every leg of the trip this year so far. Unheard of, and not to last. Spinnaker up off Holyhead breakwater, and no reason to take it down until Peel breakwater 55 miles away, I settled down to enjoy myself. The icing on this particular cake came from calling up a big cargo ship heading up the Traffic Separation Scheme and asking if it was OK to pass behind me as I had the spinnaker up and couldn’t change course much (I didn’t speak any of those last words out loud). Not only did he agree, he also thanked me for calling and wished me ‘Good Watch’, which absolutely made my day. In due course it came on to rain, and then blow sufficiently hard for me to have to take the spinnaker down hours before I had even seen the Isle of Man through the rain, but the smug satisfaction of being treated like a Master Mariner kept me ridiculously cheerful all day.

The early start and extra wind meant I got to Peel soon after lunch, and had my cunning Liverpool Locals’ plan prepared. The advice was not to lock into the marina basin but ask to stay outside on one of the moorings, or (better still, my informants assured me) lie alongside one of the fishing boats which never went out at weekends. That way I could time another early departure for part two of the crossing up to Stranraer before the marina tide gate opened.

I phoned the very cheerful Harbourmaster on the way up the coast and ran the plan up the flagpole. He didn’t salute it. The mooring buoys were on the quay being painted, and the entire Manx fishing fleet was in Peel and they were all going out on Saturday night and wouldn’t thank a yacht being in the way. I could tie up alongside one for now and wait for the marina gate to open, or I could anchor in the bay. This was a no-brainer, so he came and took my lines and arranged for me to lock in later. He’d even looked me up on his computer so he could pretend to remember my name and welcome me, which was a nice touch I thought.

However, I found myself penned in the marina with my early start to Stranraer in peril. This could be tricky but there were mitigating factors: first of all, I could tour the kipper factory that Roger had vetoed in favour of the castle two years ago, and second, I got a ringside seat for the fights outside the pub which started as early as 10pm.

Then tragedy struck: the kipper factory had not only closed, it had gone bust:

Luckily, so had the shop that rented us bikes so I had the perfect excuse not to cycle 50 miles around the island, but instead to have a swift half of Manx ale and write the post before this one in the multi-award-winning blog.

Sunday had been forecast windy for over a week (“Peel looks a bit fruity on Sunday” the Liverpool Chief Pilot had said over coffee in the chandlery on Tuesday, using most un-pilot-like language I thought), so I was grateful to be in the marina, but needed to negotiate my early start the following day. I addressed myelf to the Harbourmaster, who had good news. “I’ve been on the phone,” he said, “and it turns out they’re all here because they’ve had their quotas reduced. They’re all on four day weeks, and what with it being Sunday and this forecast no-one’ll be out tonight. Take your pick. You’ll be snug as anything in that corner.”

Foolishly, I believed him, locked out of the marina that afternoon and headed for the smallest fishing boat. It was, indeed, fruity even in the harbour, and as I motored into the corner he’d indicated I realised just how unsheltered this corner of the harbour actually was. I picked the smallest trawler, motored alongside and waited to drift down gently onto the side of it. The wind just heaved Blue Moon sideways, her shiny white fenders disappearing into the row of greasy, black tyres that line the side of every fishing boat. I was pinned in place where I landed, with the bow sticking out and no chance of moving with the wind blowing me on. To make matters worse, this fishing boat was even rustier than most, and that’s saying something, so by the time I had finished tying the mooring ropes, largely unnecessary given the sideways wind, my hands and the ropes were covered in rust.

See those waves glinting in the Spring sunshine? They were not friendly sparkling waves, they were doing their best to burst my fenders against the horrid tyres, yank the ropes through rusty fairleads and throw all my crockery onto the floor. Faced with an afternoon of being bounced and deafened, I ran away. Walked, more precisely, up the hill behind the castle which felt more like a mountain, but had spectacular views from the top…

…and further down gave a helicopter view of the nice calm marina I was no longer in:

Back on the boat I settled down for a rather miserable evening listening to the crashing of the waves, the squealing of the fenders and the howling of the wind, wondering which cunning techniques I could possibly use to motor off the trawler with the wind pushing me on. I reckoned the Harbourmaster was a stranger to small, light yachts. At least he knew about fishing boats and their schedules, I thought, as I struggled to sleep in the cacophony.

0400. It is pitch dark and I’m woken by the sound of a large, industrial diesel engine. I am out of my bunk and into the cockpit in an instant, apologies ready. Phew. It’s not my rusty hosts, it’s the boat in front I had tied onto yesterday. Must be one that missed the quota. Back to bed. Twenty minutes later, another engine, angry voices this time. Up again, no, not my hosts. But now there were more and more engines: I looked out of the hatch and lights were on all around me. I curled up in my sleeping bag and waited for the bang of rust-covered boots on my deck. It didn’t happen, but the noise carried on until 0600, when I gave up and decided to join them with an early start.

Suddenly, silence. I looked around in the early morning light and saw that every single other boat had gone, about 12 of them. The only ones left were the two I was tied outside of. Did my friendly harbourmaster know less about fishing quotas than yachts? It seemed unlikely. Perhaps he’d bribed the people inside me to stay at home. Or perhaps it was just the most extraordinary luck.

The wind had died, meaning I had no need of complicated manoevres involving springs and sprongs, I just pushed off and motored away.

Leave a reply to dreamilyimportant67224e245b Cancel reply