Coming from somewhere that competes to be one of the driest spots in the UK, I admit to finding the entire West Coast – English, Welsh, Irish or Scottish – to be a bit of a novelty in many ways. It’s not just the prevalence of rocks over mud, or the tendency of the water to be more than 10 metres deep, it’s the sheer quantity of rain. This, of course, I expected and I’m proud to say I have become quite comfortable with after two summers experiencing more rain than most Kentish sailors do in a lifetime, but what I have really enjoyed is the increased fascination with weather the further West you go, even to the extent of arguing bitterly about levels of raininess and the resignation that goes with them. Contrary to what my English education told me (The Beano, mainly), a typical Scottish greeting is not ‘och aye the noo!’ or even the more realistic ‘fair dreich today’ but ‘isn’t this terrible weather we’re having?’ as if it was not always like this.

This state of denial must be a comfort if you live here, and I particularly love the way anyone on the West Coast will proudly defend their patch as not being quite as wet as the patch next door, specifically the one slightly to the East with the higher ground where the rain gets dumped. For example, and I have personally now heard all of these: it rains on Rum not Canna, on Coll not Tiree, on Oban not Kerrera, on Antrim not Derry and my absolute favourite of all, on Manchester not Liverpool. Whilst this may occasionally be the case, I am quite sure no-one from the South East could possibly be expected to tell the difference, or find any of these places anything other than impossibly damp. My most recent experience of Liverpool illustrates the fact pefectly., but first I had to get there.

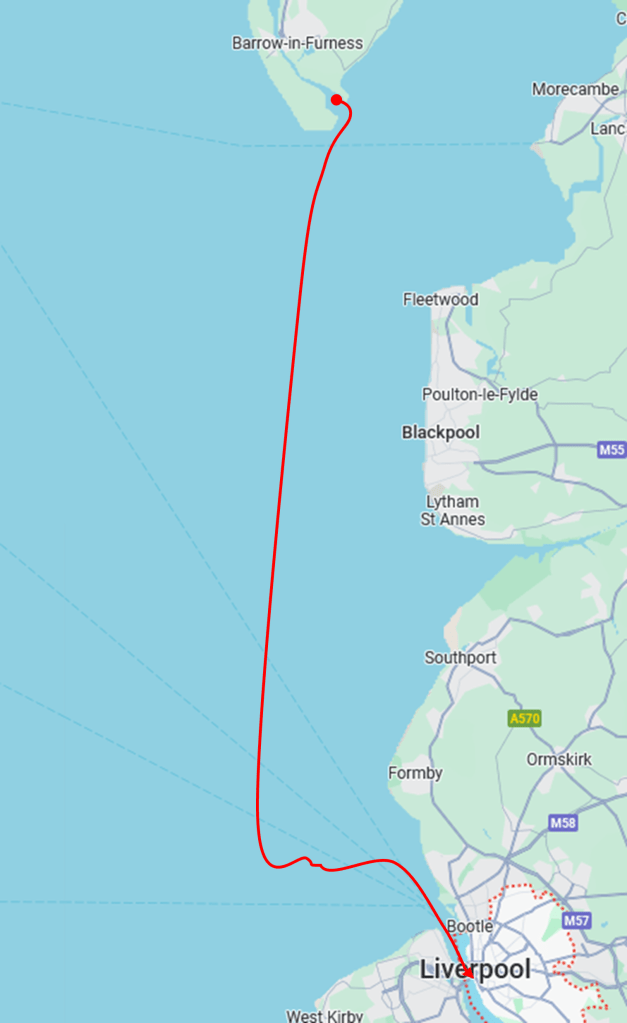

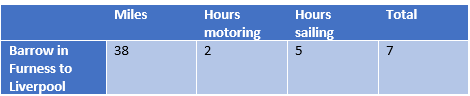

My day started in bright sunshine in the Piel anchorage, but that lasted about half an hour. This was a very early half hour too – I had worked out that to get to Liverpool at the required High Water at 1440 I should leave around 0640 – it had taken over ten hours to go the other way. I had the forecast in my favour and patted myself on the back for planning ahead and being in Piel as the northeasterly would be a perfect direction: I had got the spinnaker gear ready for a final day broad reaching in 12 knots, with my only concern being which spinnaker I would put up to get me there a comfortable half hour or so before High Water.

I was a bit surprised, then, along with the sunshine to spot the wind howling in the rigging: it was blowing 20 knots across the anchorage. Hoping this was just a local anomaly I cockily put the mainsail up on the mooring and sailed out into Morecambe Bay, equally cockily cutting the corners out of the Barrow channel and scooting along in just over three metres of water. I had taken the precaution of putting a reef in and I was glad I had – it was a steady 18 knots and we were flying along. I thought I’d postpone the spinnaker hoist until after breakfast when the breeze would have died down to the forecast levels.

It didn’t, and I was lucky to eat my breakfast on an even keel. Into the deep water off Fleetwood it all got a bit lumpy, and then the rain clouds arrived. Each one brought not just the kind of rain that would make Oban proud, but a particularly cold and sharp squall straight from the top of Scafell Pike. As it passed, the wind dropped just enough to make me head for the spinnaker, then another black cloud with gusts now of 24 knots. I reminded myself that getting to Liverpool early would cause problems as the tide would be too strong to get into the lock safely, so that I didn’t need to risk being caught in a gust with a spinnaker up, and swore myself a solemn oath to leave well alone.

This was, not for the first time, the right move. Not only did the wind stay up the whole way, it also came ahead so that we were now screaming along on a fast reach, rain periodically sweeping across the deck and into my eyes. The Blackpool tower came and went in a murky blur, then the peculiar oil fields (or are they gas? I’m not sure) and various bits of navigation software started predicting an arrival closer to 1300, or occasionally even 1230, before they would even open the lock, and when with spring tides I might have to ferryglide across five knots of tide. Reluctantly I rolled the genoa up a bit to play safe and slow down.

I needn’t have worried. As I pelted towards the Queen’s Channel it was time to call my old friend Mersey VTS and ask permission to join the procession. Yes of course, he said, just be sure not to impede any commercial shipping and head in behind the Wilson Warrior. I found the Wilson Warrior on the AIS, the definitive dirty British coaster with a salt-caked smokestack if you remember your John Masefield, and headed up to let her overtake me so I could cross over behind her.

She didn’t. She was doing seven knots, and so was I. I was now on the wrong side of the channel, keeping pace with a cargo ship, and now I could see not only on the AIS but with my own eyes an ever bigger ship coming out towards me. I remembered that last year Roger and I had actually overtaken one of these coasters, so I rolled up the genoa, put the engine on, turned almost 180 degrees and headed towards the stern of the Wretched Wilson Warrior and began following her up the channel. I would have been pleased with such a combination of good seamanship and useful time-wasting were it not that the rain had now set in as a sort of permanent drizzle which made my glasses quite opaque and all the handy iPad navigation stuff on board rather hard to read. More annoyingly, the Warrior had obviously now had some new instructions as she speeded up and started pulling away around the bend off Formby.

Looking in my metaphorical rear view mirror I saw my next playmate, the rather larger and faster Inthira Naree. She had already pulled out to overtake, so I came as close to relaxing as you can with a couple of hundred metres of Thai-registered cargo ship thundering up past you.

She carried on past, and I considered waving but thought better of it. Then, to my shock, I heard her calling me up on the radio. I fumbled around to return the call – no answer. I tried the VTS channel 12 and channel 16 – nothing. Someone else called back: “Blue Moon, you were being called on 12”. “I KNOW THAT BUT HE’S NOT REPLYING NOW!” I wanted to shout back but bit my tongue and called back again. Nothing. Using my super new cockpit radio thing I found her and made a direct call: it rang for a minute and no reply. This was odd, but it made sense to speak as we were approaching the river and it would have been nice to know where he was going so I could keep clear.

Then she slowed down and, in the absence of more information I rolled up the genoa to slow down too and see where she was going next. Then she stopped, and since stopping was less of an easy option for me with any sails up, I had to make a guess that she was headed for the main docks to port, so I headed as far as I could to starboard onto the New Brighton shore. This got me out of her way but I found myself in suddenly very shallow water but strangely even stronger tide – I was being hurled along at over five knots trying to go as slowly as possible with a reefed mainsail and an engine in tickover just in case. Then, just to add to the fun, I found myself slaloming through a whole line of moorings off Wallasey – rather closer to the shore than I had intended.

Then the radio burst into life again – it was the VTS telling the apparently no longer deaf Inthira Naree that it was safe to turn in to the docks on the Livepool shore. “There’s no outbound traffic,” he continued, “inbound is one yacht on your starboard quarter, but he’s well inside the buoy line.”

Well inside? I was virtually up the beach, and rather cross that I’d been forced there, and confused that the tide seemed stronger in the shallow bits (non sailors – the tide usually runs stronger in the deep bits). But I had no time to complain, this same tide was now hurling me straight at the Birkenhead ferry terminal, and there was a ferry just about to leave. I couldn’t head out into the river as I’d be in his way, so I had to point at the pier and pray that he’d leave in time for me to shoot through the gap he’d just left. He did, and I did, but I could actually read the adverts on the pier through the rain as I sccoted past feet away.

The upshot of all of this was that my slowing down tactics hadn’t really worked: I was almost an hour ahead of schedule and the tide was still pouring in. On the one hand, at least I now knew where the lock gate was and what to expect, on the other I was on my own this time and had to get all the warps and fenders ready while avoiding piers and ships and docks and in a bit of a rush because even with the engine in neutral I was approaching the lock at five knots. But it was very reassuring to hear a familiar voice on the lock radio, to tie up in a lock that felt like home even though I’ve only been through it twice before, and to tie up one pontoon closer to the bar than last year, to be welcomed by marina folk who knew I was coming and asked how my summer had been. Even though it was now pouring with rain I sat in the cockpit exhausted and grateful to be ‘home’ for the winter.

Then the silver lining of my early arrival presented itself. I had time to tidy up the boat, have lunch and a much-needed shower and get to the bar in time for kick-off at the main event of the day: Manchester City vs Arsenal. What better way to celebrate the end of the season’s sailing than sitting in the warm and dry, beer in hand, watching an enjoyable and largely successful football match on one side and, on the other, successive race crews coming up the pontoons exhausted and bedraggled from their Autumn Series in the now torrential rain? The answer was a very entertaining surprise: as they made their way into the bar, one group after another stopped to look at the screen and then started laughing. I’d assumed that as Liverpudlians of any colour they would be enjoying the sight of City losing at home but no, pretty much without exception someone would point at the match, where it was raining so hard that even Pep Guardiola had put on a poncho at one point, and say to the rest of the crew something along the lines of: “Could be worse, eh? At least we’re not in Manchester”.

Karen in the marina office explained to me last year, with a completely straight face, that one of the countless reasons why Liverpool is a superior city to Manchester is the relative lack of rain here. I’m writing this a few days later with the rain blocking the now-familiar view of the LIverpool skyline and thinking something that will be a great comfort all winter: it could be worse, I could be on the West Coast of Scotland.

That’s it for this year. Next year, in an attempt to come up with stories interesting enough to blog about, I am hoping to make it around Orkney and Shetland and back down the East Coast. Something is bound to come up.

Leave a reply to Margaret Cancel reply