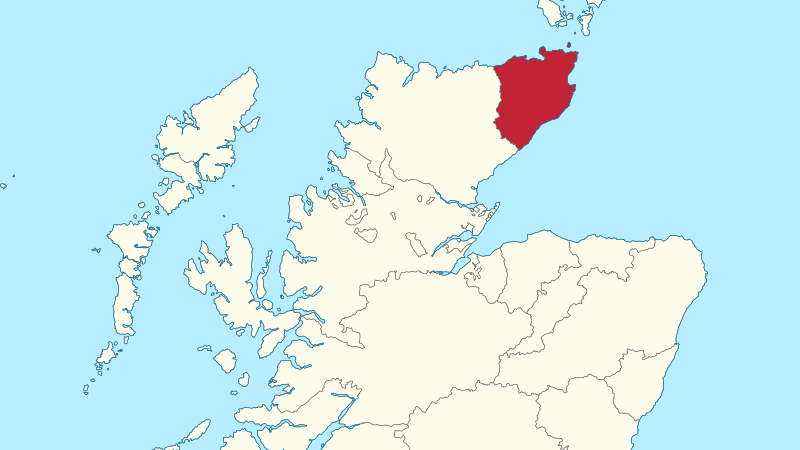

Caithness is one of those place names that I have been aware of for years and years without having the foggiest idea where it is. A bit like Ashby-de-la-Zouch for instance: a leading contender to be the most central town in England but it could be more or less anywhere, England being such an odd shape. Well now I have sailed the entire Caithness coastline and I know exactly where it is: not the centre of anything. It’s the top right hand corner of Scotland, with Thurso and John O’Groats and Wick and all those places with names like Scrabster and Lybster and Ubster and Thrumster. I promise I haven’t made any of them up. Here it is:

Rather like Cornwall is stuck on the end of Devon so Caithness is stuck on the end of Sutherland, and rather like Cornwall it seems ridiculously proud of being where it is and what it is, perhaps especially now all these old counties have been swallowed up to be simply ‘Highland’. Everywhere you look you see the Caithness flag: in shop windows, on cars, on civic signs, on flagpoles in gardens in the middle of nowhere:

Pretty much every tourist information board has something to say about how special it is, every product imaginable is described as ‘Caithness this’ and ‘Caithness that’. Famous local residents (both of them) are invariably described as proud sons of Caithness. Only in Yorkshire have I seen a county so prominent in its identity, and that’s about six times the size (with 78 times the population – true facts).

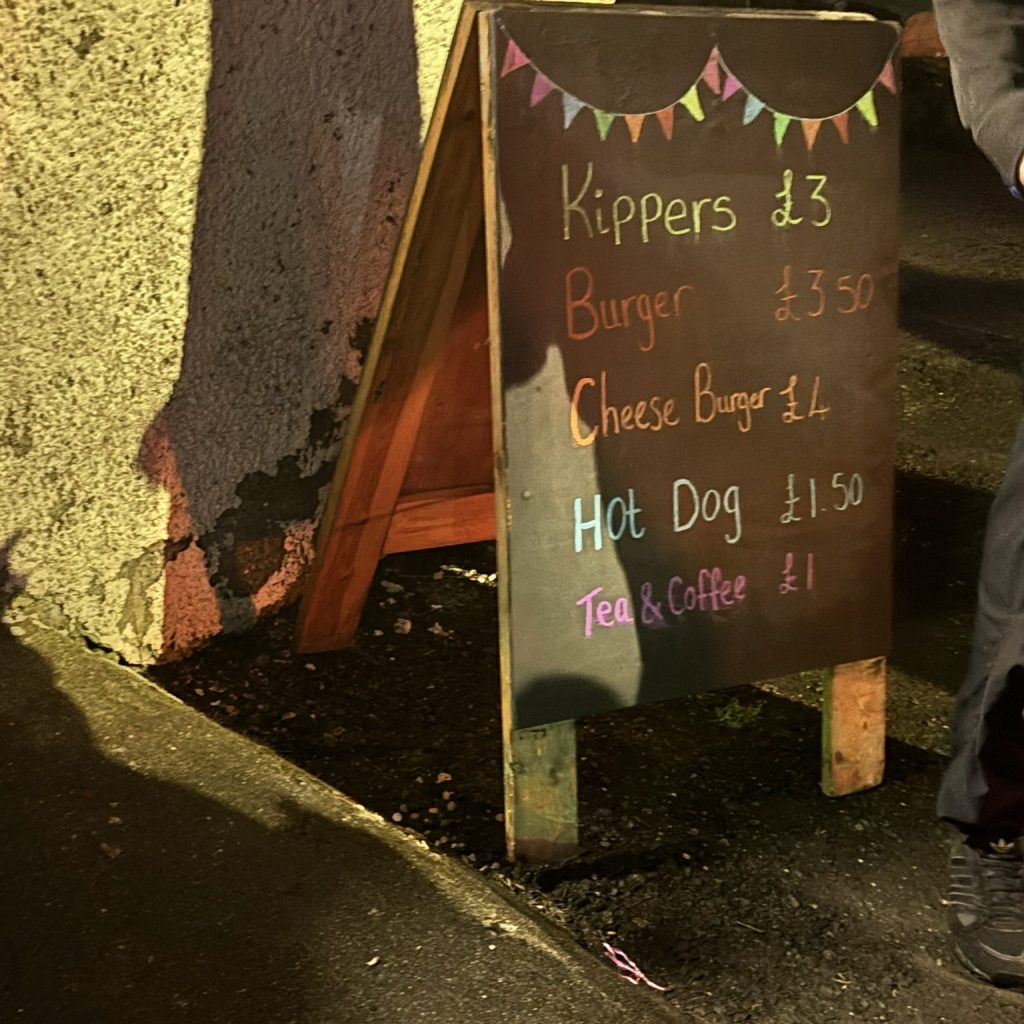

But unless you’re into flagstones (apparently Caithness’ ones are highly prized) it really has only one real claim to fame: they invented herrings here. Well, perhaps not the fish themselves, even Yorkshire wouldn’t try and claim ownership of creation (yes they would – ed), but Caithness invented salting them, curing them and/or turning them into kippers, and that makes Caithness a pretty special place in my view. Sadly, and many things about Caithness are sad, I have been unable to find a retail fishmonger that would sell me my favourite breakfast. Indeed, the only kippers I have seen other than boil-in-a-bag in Tesco are these: proudly top of the bill at the Wick Gala Fireworks food stall. Desperately sadly I had already eaten well, and even I couldn’t face a kipper at 11pm.

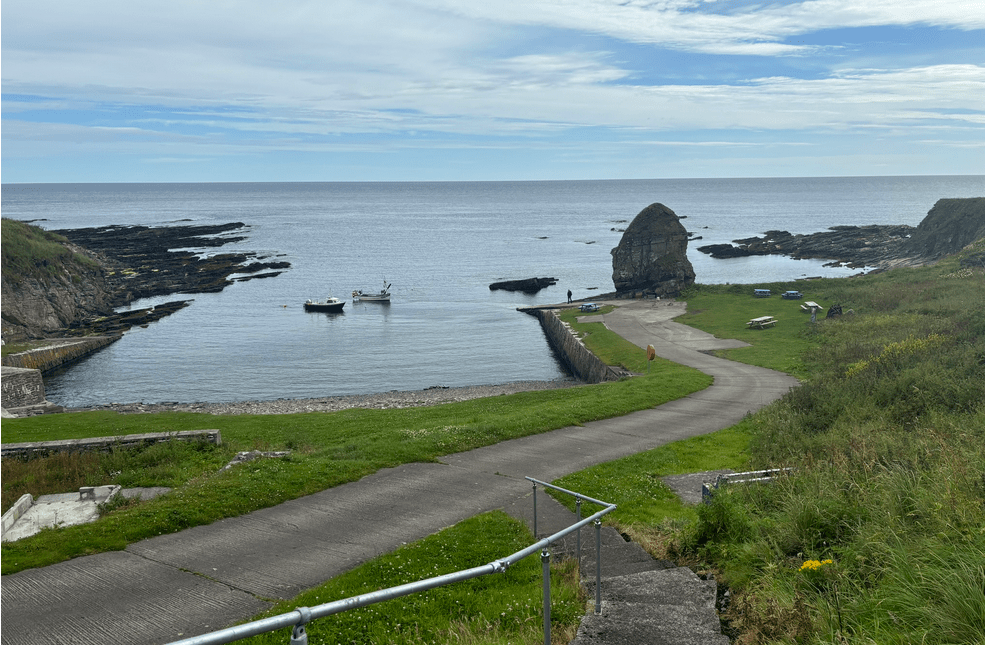

I did, however, come across the harbour where it all started, a place called, believe it or not, Staxigoe (there is also Papigoe and Whaligoe, but I don’t think they salted whales).

I also now know the rather depressing history of the herring and its cousins (not just kippers: I’m not averse to a smokie, a rollmop or even a bloater if you could ever find one these days). If you’re not up for a bit of fish history, do skip this next bit.

Apparently no-one really bothered catching herring in any quantity until the Highland Clearances at the beginning of the 19th century, when landowners had the bright if unscrupulous idea of turning crofters off the land in place of more profitable sheep, and building fishing ports and telling them to ‘go fish’. Apparently, being farmers not fishermen, they weren’t very good at it, but luckily it coincided with a boom in herring migration so they more or less only had to throw a net over the side to come up with a ton of herring which the existing fishermen didn’t bother with much as they weren’t particularly tasty or meaty. But if you’re starving because you’ve got no croft, you make do, and when they discovered that if you salted or cured or smoked these oily fish and packed them into barrels they would keep for months, the herring industry was born.

Amazingly the real boom came from exporting barrels of herring to the West Indies where they fed slaves with them; when Abolition began to dry that market up they exported to the Baltic states, which feels like a definitive coals to Newcastle enterprise, but apparently it worked well until the beginning of the 20th century when at the same time the herring stocks suddenly dwindled (over-fishing or changing migration patterns) and The Great War took most of the fishermen away to discover – like their cousins on the Hebrides – that there was a modern metropolitan life to be had away from these remote shores. Those that stayed fished for white fish until – almost every information board bluntly explains – the then-EEC fishing quotas and the Icelandic fish wars of the ’70s largely killed that off, leaving most of the local ports now supplying shellfish, and the ‘Silver Darlings’ as the focus of every town museum and village heritage centre.

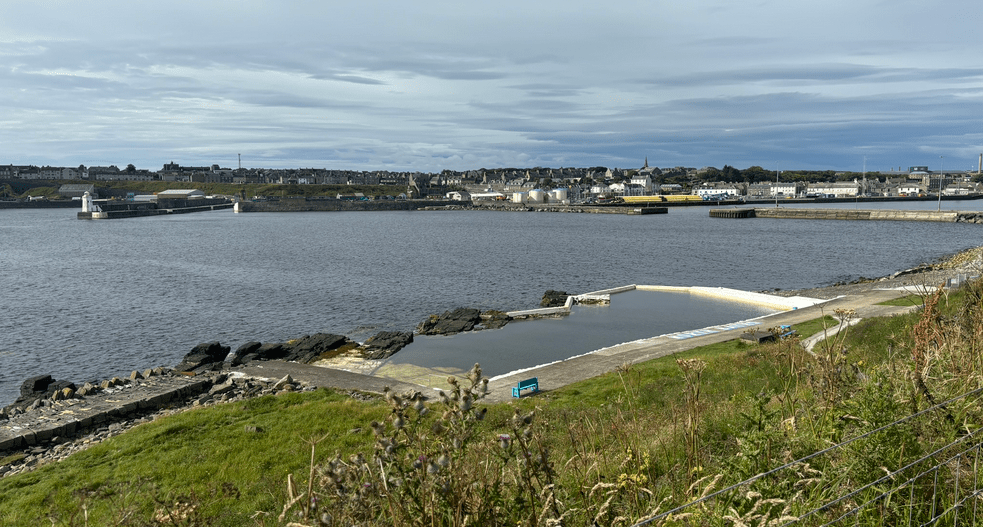

I began my journey of herring discovery in Wick, where I spent a day more than planned because it was windy, and whose museums and information boards explain that it was built by the Duke of Sutherland, the most notorious of the land-clearers and owner of both Sutherland and Caithness, who commisioned Thomas Telford (who else?) to build a town with a harbour pretty much from scratch on this ridiculously inhospitable coast. The result is massive harbour walls that even now get breached in winter storms, and a very down-to-earth, almost industrial version of the ‘planned villages’ like Tobermory and Portree on the West Coast. More recently the silver darlings have been replaced by wind farms who bring in at least some local employment, and part of the large fish dock has been repurposed as a proper marina with cheerful people who keep their boats there and chat to passers-through. In fact, the first real marina I’ve been in since the beginning of June.

I liked Wick rather more than I expected to: everyone was as friendly as the marina staff, it only rained around half the time, and it seemed to be making the best of things for a town whose prosperous past was so clearly far behind it.

Ian the Harbourmaster showed me these pictures in his office: at its heyday there were 1,000 boats based in Wick processing 1.6 billion herrings a year. Yes, 1.6 billion. On one day in 1863 they packed 24 million into barrels and carted them all off – literally, as the railway didn’t arrive until 11 years later (you’ll see how I know that in a minute).

Wick’s tourist information joined in the general theme of danger and misery on the coast, and there were constant references to shipwreck and loss of life. One of the town’s local heroes made a name for himself first by making Telford’s walls even stronger as he was born here and knew how wild the winters were, but also by developing a wreck-rescuing business so successful that he was the only one who managed to refloat Brunel’s giant SS Great Britain when she ran aground.

This rather fine new memorial to the drowned seamen of Caithness was erected last year. The sea is giving with one hand and taking away with the other

In spite of all this Wick has a sense of humour: these people could have called their cafe The Harbour Lights like everyone else, but didn’t:

Mind you, they’ll have to change it at some point as everyone who gets the joke will be dead.

It being a windy Sunday, having learned enough to gain a PhD in herring history I took myself off for a monster hike around the coastline I had just sailed past, and decided that in future I would always do this afterwards not before as it was less scary. It revealed that you could stay in the elegant Noss Head lighthouse and watch sailors racing past once in a blue moon (geddit?)…

…although noticing that the very few houses round here have slits instead of windows on the north side might give you a clue as to when to book:

The walk also took me to the two castles I’d tacked past the day before, which offered pretty dramatic contrasts. The first, sacked by an opposing clan and left to ruin:

The second, restored as an upmarket hotel but now sold to an American billionaire as a private house, to the dismay of the local community…

…and of Philip Schofield, apparently, who got married there.

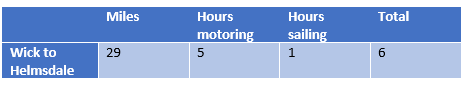

Finally the wind moderated enough to head south, to a vilage called Helmsdale which is just over the border into Sutherland, and has made something of a tourist attraction out of its role in the Clearances: it’s another planned fishing village, and it has a large memorial to those who were evicted and emigrated…

…and a combined museum and art gallery on the subject, which took all of fifteen minutes to visit even though I read every word and watched the multimedia thing twice. Helmsdale has two other great claims to fame: first, its castle hosted a very typical clan poisoning which went wrong when Lady Something accidentally poisoned her own son as well as the aunt and uncle she wanted the boy to inherit from: apparently this story was the inspiration for Hamlet; second, it is the birthplace of Scotland’s first (only?) astronaut. I would have thought either of these subjects would have made a better museum.

The harbour is having a tough year because storms last winter were so bad they flung a load of mud and stones over the wall and silted the harbour up. There are notices all over northern Scotland warning visitors to keep out unless they have shallow or lifting keels. Hurrah! A spot for me then, and a call to Donald the long-suffering but very friendly harbourmaster confirmed I’d be fine. In the absence of the majority of his passing yachting trade, Donald was happy to while away the afternoon telling me all about how during the storms you could watch the stones from the beach being flung over the harbour wall for days on end, and then about how they got the local digger down early one morning and had just begun dredging them out when the area marine inspector happened to drive by over the bridge on his way to work, saw what was going on and demanded various bits of paperwork and seabed samples. Oops.

The upshot was that I was a rare visitor. Me and King Charles III, as Donald explained within moments of taking my lines and welcoming me in, although he and absolutely everyone else in the village referred to the monarch as ‘Charlie’. Apparently young Charlie learned to fish here, it having one of the most famous salmon rivers in the world (just repeating what I read in the museum), and he likes to come down from Castle Mey on his holidays and do those watercolours. Tomorrow he was coming to unveil a plaque celebrating 150 years of the railway (built for the herring trade of course), although rather inappropriately he was coming by helicopter.

Faced with another day of strong winds I had decided that I would take this train south a few miles to a place called Golspie where you can climb up a large hill to see not only a momument to the infamous Duke of Sutherland but also a spectaular view, so I was worried that I would have to force my way through a crowd of flag-waving monarchists to get to the station or – worse still – not be allowed to catch the train at all, but be forced to wave a flag instead. I needn’t have worried: there were many police cars but the police were just sitting in them (I couldn’t help imagining them eating Haribos) not doing any actual policing, apart from the one officer on the platform who was embarassed when her friends waved at her from the train. I did wonder if I should stay just to keep Helmsdale’s end up: the welcoming committee appeared to be three people who’d put what looked like a tartan blanket over what I supposed to be the plaque.

Getting out onto the slopes of Ben Bhragghie was much better than waving a flag at a king: there were fabulous waterfalls:

..and amazing views from the top: from Rattray Head to the Cairngorms round to Inverness, the Highlands and down over Cromarty and Dornoch. I sat and ate my picnic and mapped out the rest of my week’s leisurely pottering around the Moray Firth.

The monument claims to have been erected with donations from the Duke’s ‘friends and tenantry’. From what I’d learned in the last few days I rather doubt that he had many friends among the tenantry, and apparently there are still campaigns today either to have it replaced or simply to take out chunks of stone until it collapses like a giant Jenga.

The monument looms over the village like a giant Victorian Antony Gormley

Tiring of history, I was delighted to find that Golspie was home to the first proper ice cream parlour I’d seen since Tobermory, made in Brora, the village next door, which turned out not to have an over-priced cashmere factory at all but a decent ice cream producer and a distillery that makes a good proportion of Johnnie Walker. And just to tick all the seaside boxes, back in Helmsdale Donald had recommended the chip shop which promisingly if immodestly described itself as ‘The North’s Premier Restaurant’. The fish supper was indeed excellent, but what gave it the seal of approval was that it was handed to me by a hand that only that morning had shaken the hand of the King.

He was still wearing that check shirt, and grinning from ear to ear.

Leave a comment