I make no apologies for starting my last post of the trip with some pedantry; why alter the tone of the blog now? It has always bothered me slightly that the song should really be ‘Ferry Across The Mersey’: nobody, especially not The Pacemakers, would have criticised Gerry for not singing the A in ‘across’ as it obviously wouldn’t scan, and musically would stress an off beat, but he set a poor example to the youth of the Sixties by not recognising it in the written title. Here, in my last blog facts of the year, are two fascinating discoveries: first, that the grammatical pedants Stock, Aitken and Waterman added an apostrophe on the charity recording for Hillsborough:

Second, that Frankie Goes To Hollywood covered the song as the B side to Relax. Who’d have thought it?

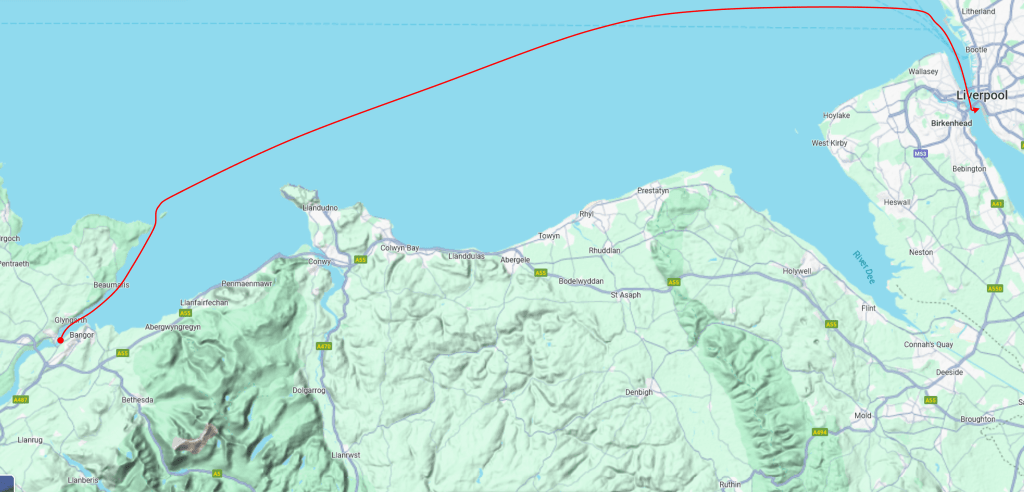

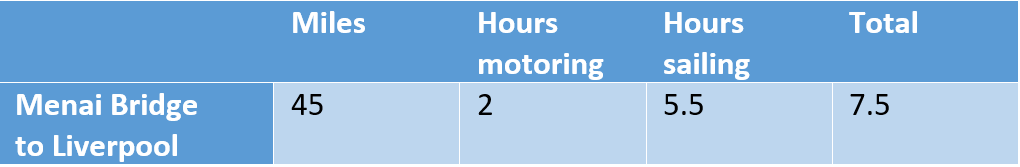

Certainly not Roger or I, and certainly not at 0530 on a wet and windy Monday morning when we woke up and reminded each other that we were on a mooring off Menai Bridge and were due in Liverpool a little over eight hours later. You may remember that I had chosen Wednesday 20th as Arrival Day because of the civilised tide; well, given that it was forecast to blow a gale from Monday afternoon to Thursday morning we had taken the thoroughly seamanlike if rather obvious decision to get to Liverpool by Monday lunchtime, but this did mean that High Water was an hour earlier, and therefore so was the alarm.

The reason arriving at High Water is recommended is because the River Mersey is quite big and has – yes, you guessed – massive tides. To get into any of the docks (and the marina is rather splendidly located two docks south of the bright lights and cultural renaissance of Albert Dock) you not only have to cross mudbanks which only cover towards High Water but also cross this fierce tide to make it into the lock. Arrive while the tide is at its peak flow (around 5 knots) and unless you can do more than six knots against it, instead of the lock you end up in Runcorn, or possibly Stockport on a bad day, and I have been there often enough for one lifetime. Yet again, the requirement is for High Water Slack, when all is calm and lovely and the cheery lock keeper waves you in while tourists and delegates at the Conference Centre cheer.

That was all in our dreams as we blearily hoisted sails only for the wind to drop and us to motor through the dark, murky drizzle past sights as allegedly interesting as Bangor Pier, Beaumaris castle and Puffin Island off the entrance to the Menai Strait, all of which were barely visible in the dark. As we rounded our final Welsh lighthouse the dawn finally broke, the weather improved from drizzle to steady rain and the wind increased to around 16 knots.

This was good as we needed to cover the 55 miles pretty smartly, but not quite enough to relax, so for once I was quite amenable to putting up the asymmetric spinnaker. This looked very glam for a quarter of an hour as we settled into a steady 8 knots surfing down the following sea. Remember that term? So did we, and as I went downstairs to write up the log I found myself lying on the keel box rather than sitting on the nav seat. We had discovered one of the several differences between a Parker 325 and an International 14: in spite of the Parker being more than twice the length its rudder is rather shorter. The breeze had only gusted up to 18 knots or so but it did so just as the rudder met a trough in the waves, rendering anything Roger did with the wheel (I’m sure it was all good) totally meaningless, while the kite flapped away merrily as if it was on one of those Beken of Cowes calendars. It had reckoned without the snuffer though which quickly spoiled its fun, and spent the rest of the morning dripping gently onto my sleeping bag.

However, this was clearly our day as this little episode turned out to be a blessing in disguise: the breeze that had promised to freshen around teatime clearly drank tea for breakfast as it was soon blowing 24 knots, in which conditions even Roger had to accept that prudence demanded white sails, one of which was also reefed so that I could do something other than ease the main all morning. This barely affected our speed and within what felt like minutes all of Wales had disappeared into the murk to be replaced by a seemingly endless row of wind farms (including Europe’s largest, don’t you know). As the tide picked up so did the wind and waves and before we could regret that it was too rough to cook a meaningful breakfast we were approaching the entrance to the Mersey and it was time to start acting like a Big Ship.

Like Belfast, Southampton, Dover and various other big ports I’ve sailed into, Liverpool has a VTS which even yachts have to obey. I’ve only just discovered that VTS stands for Vessel Traffic Service which is just plain silly: that makes it sound as if they are at your beck and call whereas in reality they boss you about. We were prepared for this, and as mentioned earlier (see And so to Belfast) I rather like being treated like a Master and Commander. What we weren’t prepared for was just how busy Liverpool still is, in spite of all its PR about its terrible decline from being the world’s biggest port and the second city of The Empire and all that. Its VTS is more like Air Traffic Control and the channel it controls begins about 12 miles out into the mudflats off the Dee right up to the Manchester Ship Canal. There were ships coming up and down the channel every few minutes, and even a holding pattern outside like Biggin Hill where they cruised around in circles waiting for their turn. What made it more entertaining was that the VTS Controller and all the pilots on the big ships and the Masters on the smaller ones were proper Scousers who all knew each other, so it made the whole thing sound like a giant but very friendly episode of Z Cars.

We called up rather apprehensively but yet again the controller treated us as if we were important: we were given a place in the procession, the ships near us were told we were there, and he even called us to invite us into the main channel when he saw that we were getting close to the bit where the buoys are literally moored on the edge of the deep water. With the tide and the following wind we had little trouble keeping up with the big boys, and even managed to follow our leader in overtaking a small coaster doing a mere five knots in the middle of the channel.

With the combination of the increasing waves and wind, the wash of so many big ships and fast pilot boats, and some truly horrid mudbanks all around, it was quite the bumpiest sail I’d had all trip, and I was very glad that we had made the effort to get there before it really started blowing. The pilot books suggest that even though the Mersey is a big river it’s dangerous for yachts in strong onshore winds, and if you miss the marina there really is nowhere else to go.

We had naively assumed that things would get calmer once we were past New Brighton and into the river proper: now we could see the sights of the city with double the cathedrals and football stadia, to say nothing of huge and very busy docks, but with all the traffic and wind and a still fast-flowing tide it was now like the proverbial washing machine and taking the sails down and rigging warps and fenders was one of the trickier manoeuvres of the trip as we were bounced about off Birkenhead. Moreover, thanks to our extraordinary racing skills (mainly the extra wind) we were over an hour early and whilst the tide was no longer doing five knots it was nearly half that, and getting into the marina lock wouldn’t be a doddle.

Hence the cheap and obvious title. Ferrygliding, for the non-sailors, is actually a thing: faced with a hosing tide, rather than pointing at your destination and being swept past it, you motor into the tide at the same speed as it’s pushing you so that you stand still over the ground, then edge sideways with enough throttle to keep you in line with your goal. I imagine it’s a bit like manoeuvring a geostationary satellite into position, although I’ve never tried. It’s what I should have done in the dark arriving at Caernarfon, which perhaps explained the look of apprehension on Roger’s face when the lock keeper asked us on the radio to wait outside while the wind farm boat ahead tied up, that and the rather embarrassing realisation that I was heading for a brick wall which looked like a lock instead of the actual lock. Hurrah for Specsavers, and for a new engine, the combination of which got us safe into the right lock and eventually the right marina.

I’d made a lot of right decisions here: it was the right marina in every sense: a properly warm welcome from Aaron the manager who not only showed us to our berth and took our lines but also timed his tour of the facilities to take just long enough for Roger to tidy up the boat again; and the right time to arrive: by the time we’d had lunch it was blowing very hard and a full gale by teatime. It’s also in the right place: five minutes’ walk from Albert Dock and fifteen on an e-scooter or bicycle from Lime Street. Liverpool is also the right city to keep your boat in for the winter: even buzzier than I remembered, full of pubs and bars and restaurants that were jammed even on a Monday night, so plenty to distract from boat work. All only about half an hour further from home than Emsworth where Blue Moon usually spends her winters, and Liverpool has even more pubs and fish and chip shops, while Emsworth barely has a single slavery museum or Tate Gallery.

Something felt odd though, and it wasn’t just being in a big city; I had after all been in a few towns and cities along the way. It only dawned on me on the way home: I was back in England, for the first time since April, having covered almost all of Wales, all of Northern Ireland and what felt like most of Scotland but astonishingly is only about half of it. People have started asking me the best bits, and the worst, and before I sign off for the winter I’ll do a little summary and get working on those maps that the public seem to demand. But I can honestly say, perhaps excepting a few moments of doubt in the Bristol Channel and off Padstow, that I have to one extent or another enjoyed every bit of the journey so far, and I can’t wait to get started again next April – especially because I’ll finally get to spend some time on the other, less explored, side of England.

Leave a reply to Karen Cancel reply