Fosdyke is not, and never will be, one of Great Britain’s major ports. It is about 10 miles up an incredibly narrow and improbably straight river which leads, eventually, to nowhere bigger than Stamford. It has three houses, a boatyard, a low bridge that doesn’t open and a pub. At low water it is, and this is a fact rather than an insult, a ditch.

But, and this is why it is on the itinerary, it is the closest place you can sail to to the home of Parker Lift Keel Yachts: Boston is closer but you need a trawler to be allowed in. Moreover, some of the Parkers were launched at Fosdyke, others simply put on lorries and taken to where their purchasers wanted them. No-one has any records of whether Blue Moon was launched here or at Titchmarsh Marina in Essex where her first owner kept her, but I am covering both bases. And no trip to South Lincolnshire is complete without a pilgrimage to the home of lift-keel yachting, although the site requires more archaeological research than Skara Brae since Parkers sadly folded in 2009.

Peter had already made his excuses and was booked on the train home, but poor Tom could not escape: he’d been warned about this but could not have been expected to imagine a Sunday morning in the Polish bakeries of Boston, followed by a trip out to the village of Kirton where we paid our respects at the holy shrine:

…followed by a leg-stretching traipse back to the river across the flattest land either of us had seen outside the prairies:

But it was well worth the effort in my view: when we got back to the boat we were accosted by the owner of the motorboat next door. “They were built here, you know”, he said, pointing at Blue Moon. “Yes, that’s why we’re here,” I answered. He beamed from ear to ear. “I used to live next door to the factory,” he said. “Terrible shame, they were a great firm“. Then we met Tony, who had been waiting for us to get back to the boat. He used to live next door to Bill Parker and was full of memories of truckloads of lift-keel yachts being exported around the country from Kirton, and Boston having a sailing club with an active racing fleet. He’d even bought his last sailing boat from Hoo on the Medway, my home village, and became quite emotional at the connection. Finally, David, the owner of the boatyard and the pub. He’d launched Parkers at his yard and bought the moulds from the receiver. “I could build you a new one” he offered, eagerly. I rather felt that running a small boatyard and a successful gastropub was a more profitable career, but it is lovely to think that someone with more money than sense might one day read this blog, decide they need a brand new Parker 325 and commission David at Fosdyke Yacht Haven to build one.

Friendly and rewarding as our visit to Fosdyke was, it was hard to imagine how to spend a second day there, but leaving is almost as scary as arriving. This might give you an idea of what the tide does:

You can, I hope, see why leaving at slack water is recommended. So we sat and watched brown water charge past as if it was coming down a large mountain, and when it began to go at a mere walking pace we swung out into the Fenland soup and headed back down the channel.

Out in The Wash we were treated to the full unique Wash experience. First, the sight of the entire Boston fishing fleet waiting inside a sandbank for the tide to let them go home to land their catch:

Then the best part of a day anchored in the middle of nowhere, in three metres of water, behind a barely covered sandbank, waiting for the tide ourselves so that we could get into Kings Lynn on the last of the flood before it got dark. Luckily the sun shone and Tom managed to polish off half a dozen crosswords while I tried to memorise the page of instructions for getting into Kings Lynn up a twisting channel with buoys that are moved weekly. We made it, again in time for supper, this time in the only remaining Hanseatic warehouse in the UK, although its unfortunate name (Marriott’s Warehouse) meant we spent the evening expecting to be offered some ghastly room service or a dip in an over-chlorinated hotel pool.

Unlike Fosdyke, Kings Lynn was once the largest port in the UK by quite some way, so pretty much every tourist sign seemed keen to tell us, being England’s only Hanseatic Port when trade was with Northern Europe rather than the Americas – something that the Reform-voting neighbours in Lincolnshire must be permamently perplexed by, although I imagine that’s not particularly unusual. Like all good well-preserved port towns, it is preserved because when the trade moved to Liverpool and Bristol nobody built any more buildings in Kings Lynn, expect for the most hideous Sainsbury’s, so it is all very beautiful for a rather forgotten North Norfolk town. It has loads of interesting features, including, in no particular order, a range of vaguely Hanseatic-looking buildings (oh yes, I’ve been to Lubeck)…

…a Queen Anne car park…

…with a name that can only ever have made sense one day in seven…

…another excellent fishing museum, this time with model kippers…

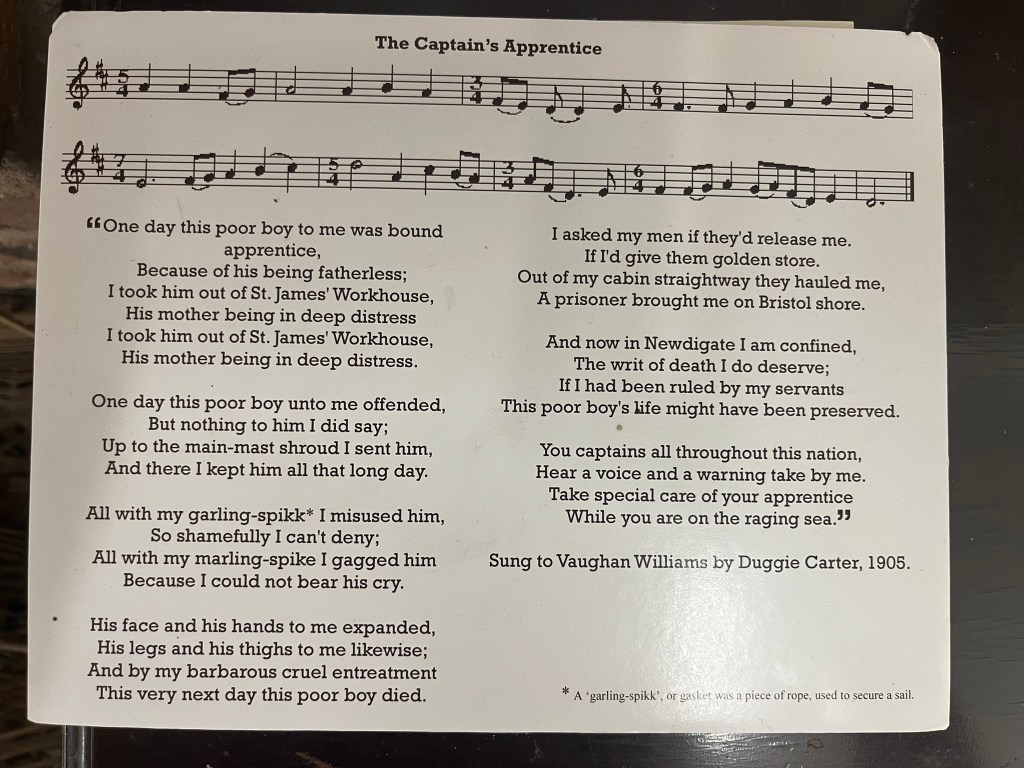

…and also a rather disturbing sea shanty supposedly sung by a local to Ralph Vaughan Williams when he came by collecting folk songs:

We were a little surprised to see this so prominently displayed in a family museum. It read like the synopsis for Peter Grimes so I can only assume VW decided to go back to Chelsea and stick to more wholesome ditties featuring orchards and rosy-cheeked maidens and left the harsher world of the East Coast to its local operatic hero to do the job a few decades later.

Kings Lynn also boasts a Minster that would impress any visiting Lubeck-burghers…

…with a rather fabulous organ…

…on which there would be a recital that very lunchtime by a visiting organist from Denver! This would be something to experience, I had a half-memory (wrong, it turns out) that Carlo Curley came from Denver, and in any case he’d have to be good to come all the way to Kings Lynn to play.

We went. We were the only members of the audience not directly related to the organist, who is still studying for his Grade 8 despite being in his mid-twenties* and does indeed come from Denver, which is a small village just down the road from Kings Lynn. The Vicar (surely if you have a Minster you get a better title than that?) introduced him as “Thomas who fills in for us on Sundays when no-one else is available” which is hardly a ringing endorsement. To give Thomas his due there was only the one wrong note I noticed, but we could have done with fewer transcriptions of film scores and ‘compositions’ based on re-writing stuff by that wretched Max Richter.

Enough sniping, Kings Lynn was lovely, but all good things must come to an end and we had planned to make our next stop the even more Norfolk-y port of Wells-next-the-Sea, which lies the other side of a monstrous sandbank but has deep water all the time, once you’re in. We could even dry out on Holkham beach where surely everybody has flown a kite at some point, and I could scrub the burgeoning weed off Blue Moon’s bottom. Funny how this has become more of an issue as we head south into water more than 12 degrees.

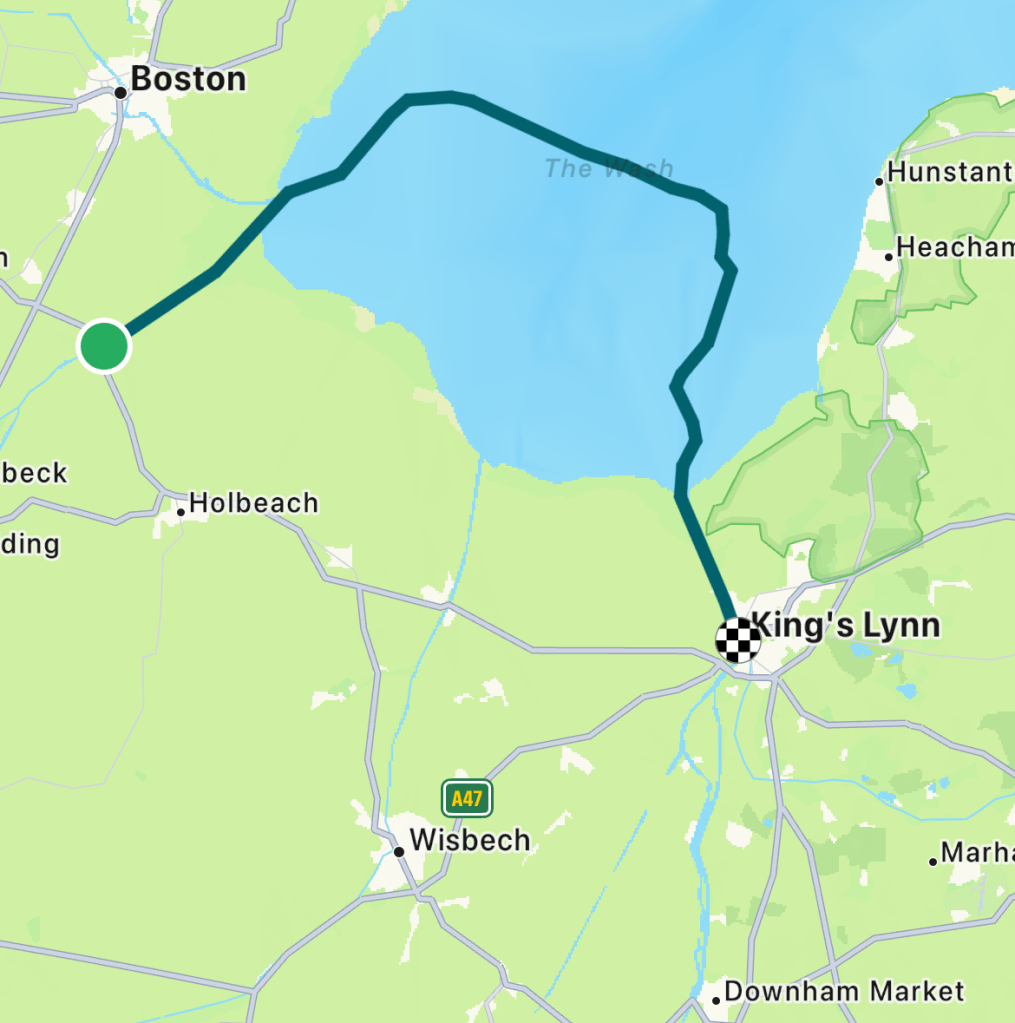

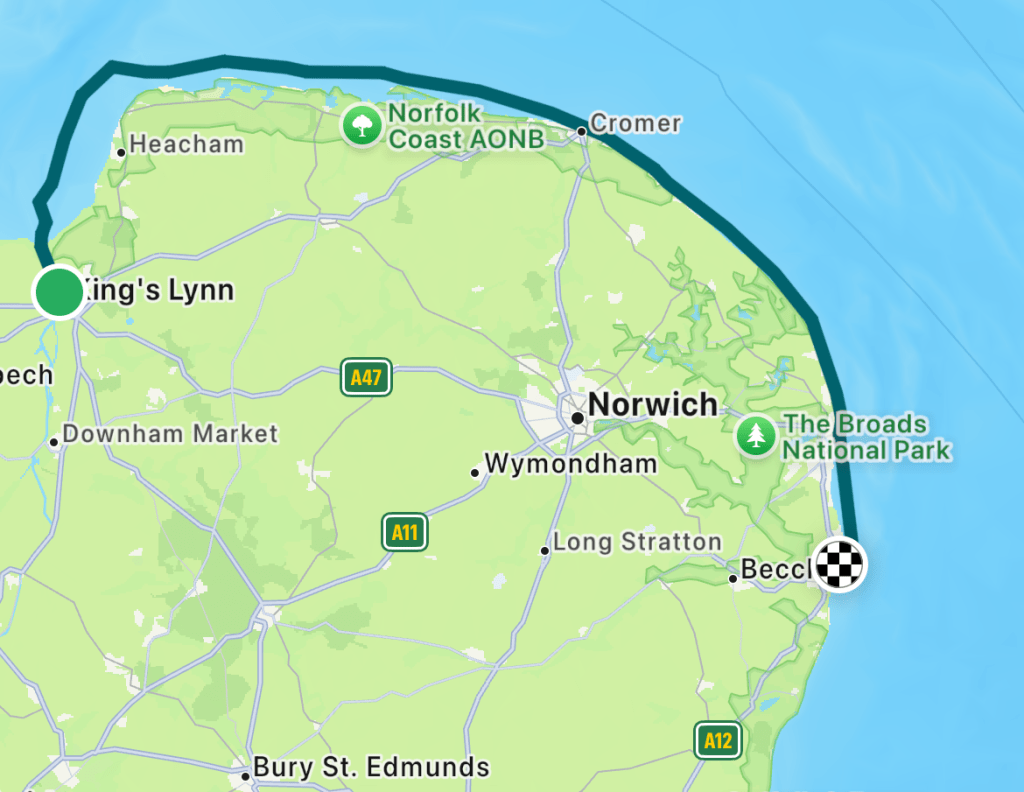

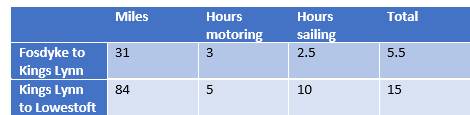

Two things put paid to this plan: first, an impending big blow which would make our final destination – Lowestoft – an even more challenging leg into 30-knot southerlies; and second, the discovery that Wells really is now next-the-sea rather than on-the-sea: recent reports suggested that, like Blakeney and various other ex-ports on the Norfolk coast, it had seriously silted up. Blakeney is barely accessible at all, and Wells now reckons on an hour or two around High Water. This was not going to help much in our ambition of getting to Lowestoft as it would now take two days out of the schedule, guaranteeing that we’d be sailing into the big wind just as we got to the famously nasty and wave-filled bit of sea off Great Yarmouth. It was a shame to miss out on the whole North Norfolk coast but the only sensible thing to do was to make one hop from Kings Lynn to Lowestoft which, at 84 miles, was going to be the longest leg of the entire trip.

Luckily the weather sort of played ball. It only rained for about an hour, and mainly the sun shone, and mainly the wind was quite helpful. We had another of those ‘green to green’ conversations with a coaster on the way out of Kings Lynn:

Hilarously, we misheard its name and thought it was called Swede Carrier. We wondered if its sister ships were called Turnip Carrier and Beet Carrier. We were in Norfolk after all.

Then it was a case of threading our way back through the buoys in the middle of nowhere for a couple of hours while making breakfast, and then we were out of The Wash and onto the rather more straightforward if less exciting coast of North Norfolk. Hunstanton, Brancaster, Burnham Overy, Wells, Blakeney, Cley, all whistled past as we tried to make things more exciting by putting a spinnaker up in 18 knots of breeze. I was grateful for Tom’s dedication to the helm: not letting things get too interesting in a lightweight cruising boat is well within the skill set of a serial Quarter-Tonner owner. All are places best visited on a smart out-of-season motoring holiday we decided, as the sand banks between us and them reared up in an endless ridge of bright yellow. Around Cromer things briefly got interesting: luckily we’d taken the spinnaker down by now as it was getting breezier, and good job too because the sea of crab pots we’d been warned about by everyone we’d spoken to for the last three days suddenly materialised. They were nothing on Arbroath, but dodging them gave us something to do for an hour, that and taking pictures of the pier.

Eager readers will also notice the presence, to the left of Cromer, of something which could perhaps be called a cliff. To my surprise these continued for a few hours, putting paid to my earlier assertion that there weren’t any between Flamborough and Ramsgate. If there are awards for geographical education, the blog is in line for a few more.

The rest of the day was spent arguing about whether you can call a chunk of crumbling sand a cliff, wondering how we’d hit some of this famous sand off Cromer when the depth gauge read three metres, putting the spinnaker up again and taking it down again ten minutes later, turning the engine on and turning it off again ten minutes later, arguing about whether you really do pronounce Happisburgh ‘Hazeborough’…

…cooking a fine curry on the move, putting the lights on and arguing about whether the brightly lit ship heading towards us not on the AIS was a dredger under 100 metres under way but not under command or a vessel engaged in seine trawling with nets on its port side. Unable to resolve that debate we headed for the safety of Great Yarmouth beach, which to my surprise is full not of fish warehouses but funfairs, all lit up to such an extent that we could barely see anything else, let alone the lights of navigation marks. Hurrah again for the chartplotter, which shortly after 2300 merrily guided us not just into Lowestoft harbour but right to the very pontoon under the very crane where the last time I had been here we had opened the sail storage boxes on our Dragon trailer to find them full of three-day-old kippers. My, how we had laughed. Such japes! Those were the days.

Today, I am sorry to say, the Royal Norfolk & Suffolk Yacht Club (non-sailors, please, keep a straight face. It’s a really nice place and very down-to-earth, honestly. They do kipper barbecues at sailing championships after all) is rather given over to huge motor boats, and one of these was moored right in the middle of the visitors’ pontoon, occupying all of the last three places left in the marina. We motored up to it and wondered in stage whispers whether one of us should get off and move it along so the other could bring Blue Moon alongside the pontoon. This strategy sort of worked: a woman’s head appeared but she appeared to be both very angry and a little detached from reality. “We’re all asleep,” she yelled at us, with the delicate tones of a troublemaker in the Queen Vic in Eastenders and in direct contradiction of the facts that our eyes and, especially, ears were presenting to us, “and we can’t move, we’ve run out of fuel. That’s why we’re on the effing fuel dock. Go over there and wait!” I’m sorry to say that in one instant she had summed up the gulf between sailors and powerboaters; I’m even sorrier to say that in the heat of the moment Tom forgot that he is, for now at least, the owner of, in addition to various race boats, a powerboat even noisier and more fuel-thirsty than our supposedly immobilised interlocutor. Even in the dark I could see him draw himself up to his haughtiest height. “I’m afraid, ” (if only he’d said ‘Madam‘!) ” it doesn’t quite work like that.” Class Warfare loomed, but was mercifully defused by the arrival on deck of Mr Powerboat, whose parents it later turned out were some sort of ex-Commodore of the RN&SYC and knew the ropes, literally. Within minutes boats had been moved, lines had been taken, hands had been shaken and pleasantries exchanged. After 15 hours sailing past all of Norfolk, we were in Suffolk, in a yacht club I knew better than most, and as I fell into that sleep that sailors fall into at the end of a proper passage, it felt very much as if the adventurous, exploratory bit of the trip was over.

As you’ll have gathered, I’m no stranger to Lowestoft, having been to countless sailing events there and even having bought our Flying Fifteen from a club member. I’m sorry to say that I had only once crossed the bridge from the yacht club to the rest of the town, so here was an opportunity to redress that omission and explore the attractions of Northeast Suffolk’s major conurbation. As I am sure you’re aware, Lowestoft is famous for only two things: it is the UK’s most Easterly town (and one of the answers to that railway station quiz I posed two years ago and have had not a single entry to: A tale of two islands); the other is that it is the birthplace of my musical East Coast hero, Benjamin Britten. Sadly, but given my acquaintance with Lowestoft, not so surpsingly, the physical manifestations of these are rather underwhelming. This is the town’s celebration of its most famous son: a ’70s shopping centre that would appall someone from Gravesend:

They had tried a little harder with Lowestoft Ness, which is the actual Easternmost point of the UK, but it was impossible to ignore the fact that the Ness itself was surrounded by the giant Bird’s Eye factory, which was belching something that looked like smoke but smelled like burnt breadcrumbs out of giant vents into the stiff breeze that we had cleverly avoided beating into.

The council had done a better job here than with the shopping centre with a bronze compass rose detailing distances to the capitals of Europe. Sadly someone had stolen the other half with the rest of the world on it.

Further disappointments were to follow. First, we had spotted the Bird’s Eye factory shop, which would be a real treat. We imagined all sorts of fish finger-based merch, and I rather fancied myself finishing the trip in a Captain Bird’s Eye sailor’s hat.

To our intense disappointment, the interior made Booker look like Harrods, and there was no sign of The Captain beyond some cut-outs. Just a small collection of chest freezers containg frozen peas and chicken nuggets, and a woman wearing a blue hair net to prove it was a factory, who, sensing potential customers, instantly hid behind a freezer.

Never mind, there were still 40 minutes left before the Lowestoft Maritime Museum closed, so off we trotted.

It was indeed open until 4pm, but in a very sensible excercise in crowd control, the last admission was 3pm. Never mind, a picture outside is as good as a whirlwind tour, and I have another ‘must return to’ destination to add to my list. You can never visit too many museums featuring kippers.

Luckily, Lowestoft still had three small aces up its sleeve. The first was the local Wetherspoon’s stepping in where the Tourist Board failed, by bring our attention to Lowestoft’s third claim to fame: it is where Joseph Conrad arrived from Poland, barely speaking a word of English, and pending the invention of Linguaphone signed on to a Lowestoft trawler to learn English.

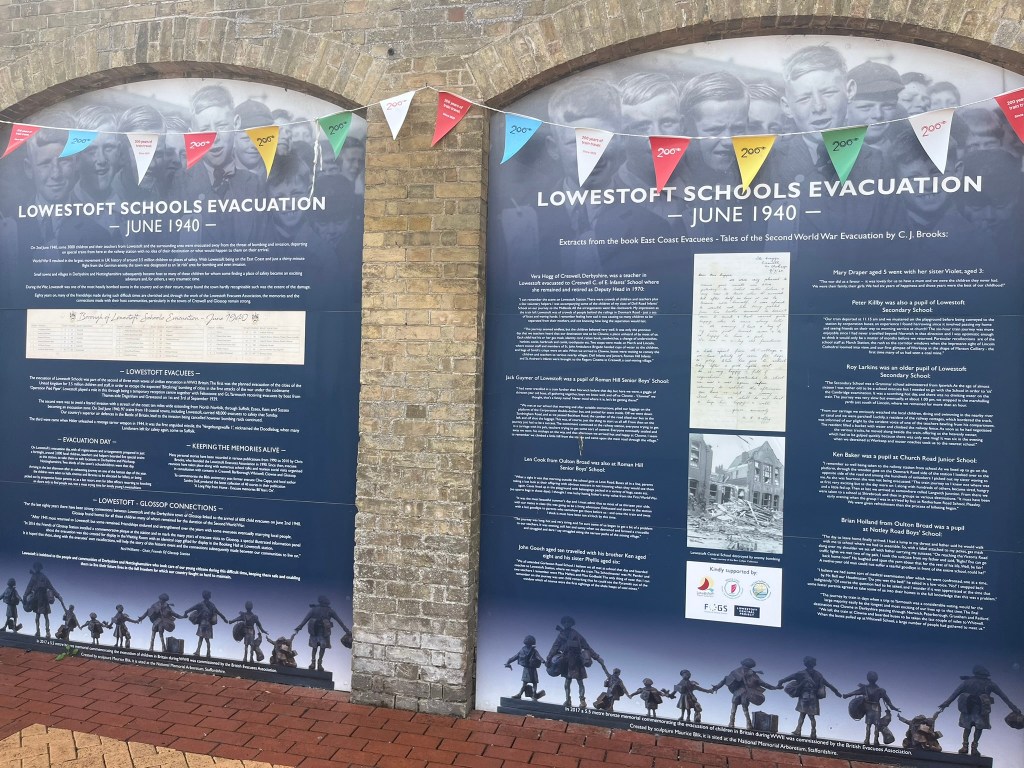

The second was the discovery of something I’d never seen on a railway station before, but could be on quite a few: a celebration first of the arrival in Lowestoft of over 500 children on a Kindertransport in 1938, when rather impressively they were met by the Mayor and this shining piece of proud local journalism:

…and then of ‘Evactuation Day’ in 1940 when all of Lowestoft’s children were loaded onto trains one summer Sunday and taken to mining villages across Derbyshire where they were less likely to be bombed or invaded.

The third was the best though. In spite of being overrun by motorboats, the Yacht Club was as welcoming as it has ever been. I knew that Russ, the legendary barman, had retired long ago but he’s been replaced by someone almost as entertaining who lectured us at length on what to do in Southwold and which puddings should be avoided, and Tom’s deconstructed fish pie more than made up for the Bird’s Eye disappointment. God was back in his heaven, and all was right with the world.

*Just to pre-empt any comments from immediate family – I acknowledge that I still don’t have Grade 8 in anything despite being in my mid-sixties. But I did get a Distinction in my Grade 5 Theory a couple of years ago, I’ll have you know, of which I am ridiculously proud.

Ah yes, the invitation of sorts. I thought it would be remiss not to mention that I hope to be in St Katharine’s Dock on Wednesday 17th, and if any landlubberly London-based readers would like to pop along to say hello, you would be most welcome from about 5pm. There is, of course, a Waitrose next door so I might have a chance to get a few beers in, and if it’s wet we can go to the dreadful-but-convenient Dickens Inn. Perhaps you could let me know if you’re planning to come so I don’t accidentally buy all of Waitrose’s beer and sink the boat. Also I can then let you know where I am, which might be in Gravesend or Southend instead if wind or weather conspire against me , and you might decide that you’d rather stay at home than go to either of those places.

Leave a comment