A delayed post this one, I’ve been racking my brain for days trying to come up with a hilarious title based on washing cycles and totally failed. There must be something in Quick Wash, surely? Answers below please, or multiple award-winning opportunities will be lost!

I’d been looking forward to The Wash with a familiar mixture of excitement and nervousness bordering on fear. Excitement because: (1) I had never been there; (2) it’s a famously odd place to sail with big tides, masses of sandbanks far out to sea, rivers like canals and places that you don’t associate with the sea at all; but most importantly (3) it’s where Blue Moon and all her stablemates were built, near Boston, along with the thousands of championship-winning dinghies that Parkers built before they turned their hands to lift-keel cruisers. I grew up reading Yachts and Yachting and drooling over Parker 505s, which won rather more World Championships than this blog has won awards (so far, at least). Fear because (1) it has terrifyingly strong tides which sweep you under bridges if you make a mistake; (2) those sandbanks far out to sea can shelter you in some directions but expose you to gales in others; (3) you can only go up these canal-rivers with the tide, but it is so strong that you’re advised only to arrive in the five minutes of slack water between the flood stopping and the ebb starting, so (4) the name of the game appears to be to leave any Wash port at High Water, take the terrifying tide down to the sandy bits, on the basis that it hasn’t swept you onto any sand banks you then anchor behind one, hope the wind doesn’t change to make it exposed and wait until the carefully-worked out time when you can leave again to go up the next canal-river to arrive at your destination at slack water so you don’t get swept into the nearest bridge.

As you can see, I had done too much research and the complexities of doing these passages had already begun to make my brain ache even before I arrived in Hull. To make matters worse, my every move and working-out would be observed at close quarters by two very experienced sailors. One – Peter – was more familiar with Parker’s previous source of fame, the Lark dinghy, than with anything with a keel on it, so he could probably be hoodwinked as long as I didn’t hit anything too obviously, but the other – Tom – has piloted a range of yachts, both his and other people’s, around all manner of tricky coastlines with a fair degree of success, so I felt under some pressure to at least appear to be in command of these situations. At least if it all got too much I could give him the pilot book and suggest he had a go.

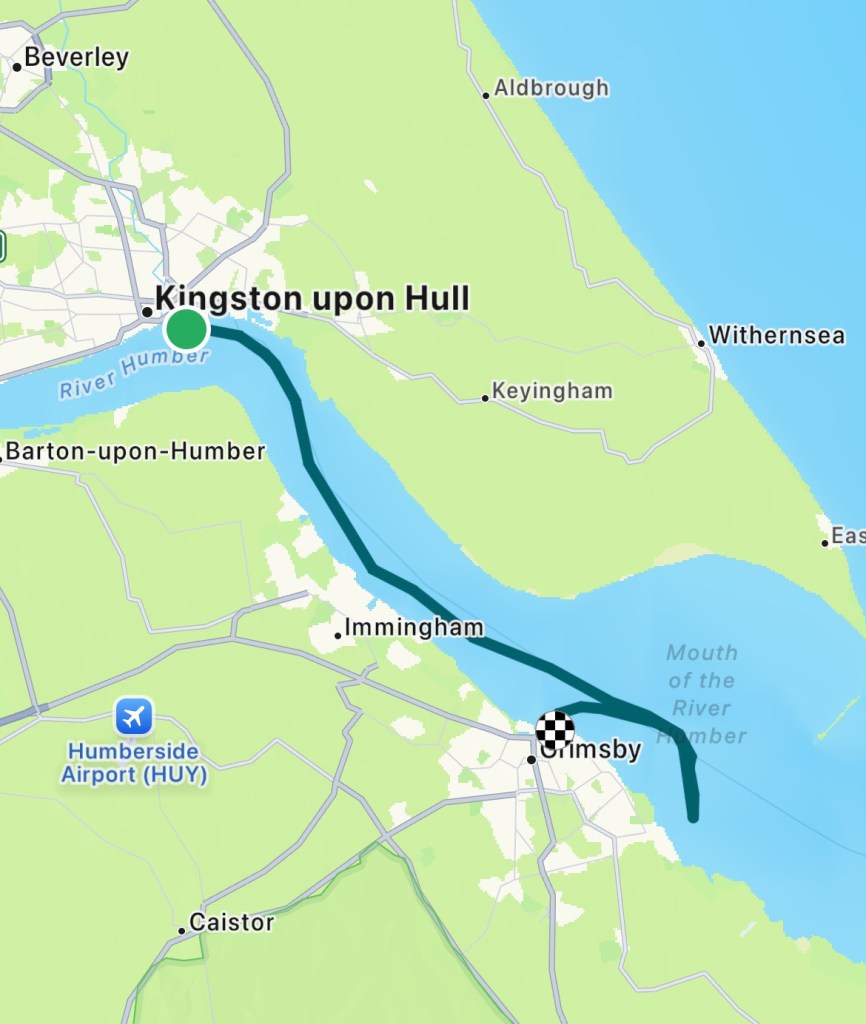

The Humber turned out to be a very good training ground for The Wash: it has almost as much tide but you only have to wait until three hours before High Water to be let into its harbours, and its banks are made of mud so more forgiving if you get your sums wrong and hit one. On the other hand, it is full of ships, as we discovered when we innocently set out from Hull Marina, as late as the lock keeper would allow us, and found a constant stream of big ships heading every which way. This did allow me to put down a seamanship marker when one of them suddenly crossed to our side of the channel to dock and called us up on the VHF, which allowed me to show off my fluent seadog ship’s captain radio technique as he thanked me for suggesting “a green to green passage”. The crew were suitably impressed, and I had a point in the bag already.

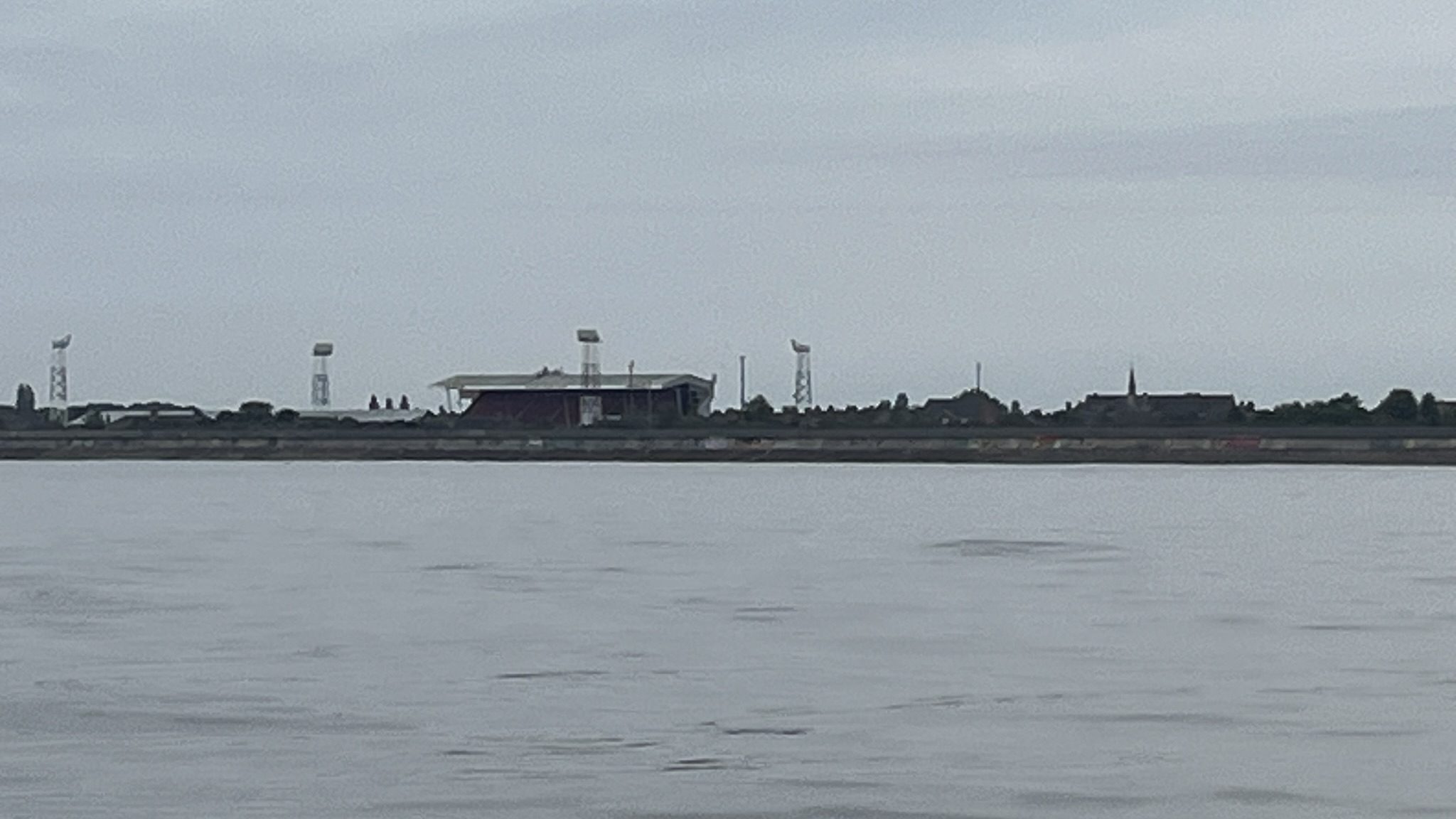

Our destination was Grimsby, and you might well ask why. I had two reasons: one, that it was the only place to leave from the next day to get to our first Wash Port at the required High Water, but more importantly a legendarily rough fish dock is exactly the kind of working port that I wanted to visit on my tour of the UK. I have managed to visit Liverpool, Kinlochbervie, Scrabster, Peterhead, Newcastle and Sunderland, and Grimsby is the last one left. Dover doesn’t count, it’s just ferries and marinas. Having visited Grimsby, I would urge any yachtsman to go as it has to be one of the most welcoming places on the trip, with minimal rough fishiness. We ‘only’ had to anchor for three hours off a bleak beach in a rising wind that we were increasingly not sheltered from before we were invited to lock in to a thoroughly authentic fish dock (no 2, since you ask), dodging ships coming out and generally feeling like we were part of the maritime business of Grimsby. Far from tolerating yachts, the lock keeper seemed delighted to see us and came out to say hello before ushering us onwards to the even friendlier Humber Cruising Association where there were pontoons, showers and a very buzzy club bar full of friendly folk waiting to sell us beer.

It being Friday, and Grimsby, fish and chips seemed in order but here we were disappointed: Google Maps promised any number of fish outlets in walking distance, but closer inspection revealed that they were of course all wholesalers and distributors. This post’s fun fact: no fish is actually landed at Grimsby these days but it is by far the UK’s leading fish processing town. Only one place looked like a retail outlet – the Grimsby Street Kitchen sounded just right for a North London yachtsman and his urbane friends – but it turned out to be an actual street soup kitchen.

Hurrah then for Cleethorpes, another unexpected sentiment that I can thank this trip for. Our new friends at the club were quite clear that if we wanted fish and chips we would have to walk the two miles to Cleethorpes, but it would be worth it if we went to Steel’s on Market Street. Sadly their local knowledge didn’t extend to the coastal path being closed off to make either a nature reserve or an extension to a fish processing warehouse, so we ended up wandering around the fish-industrial estate for an hour or so, but at least we can confirm that Grimsby is indeed the UK’s leading fish processing town.

Catching the train to Cleethorpes is something most of Nottinghamshire used to do on their summer holidays, but it was just one stop for us to be dropped into a world rather removed from Hull and Grimsby: a completely preserved seaside town (preserved, as is Whitehaven, presumably by having its best days behind it) with the most extraordinary railway station…

…which is more like a seaside pier than the pier itself…

…along with a wide range of seaside amusements, of which this is just the finest:

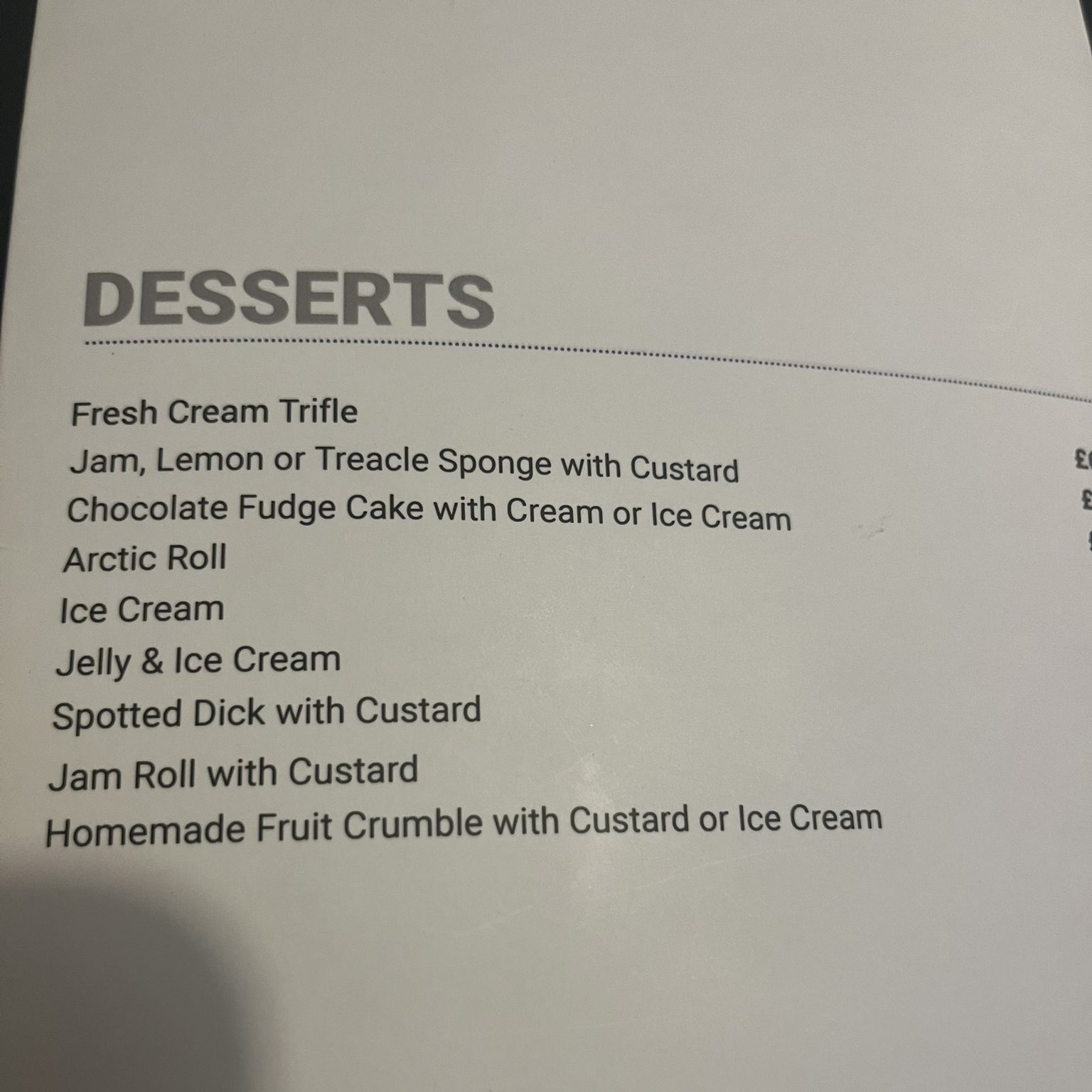

The journey was worth it. Imagine, if you will, the most traditional fish supper served amidst the most traditional decor by the most traditional waitresses. Think pots of tea, slices of buttered white bread, stern women in black uniforms with white aprons, thick carpet and velour padded chairs. You have Steel’s Corner House Restaurant, and if you are ever in Cleethorpes you must go there for an experience that I had not expected to survive into the blogging age.

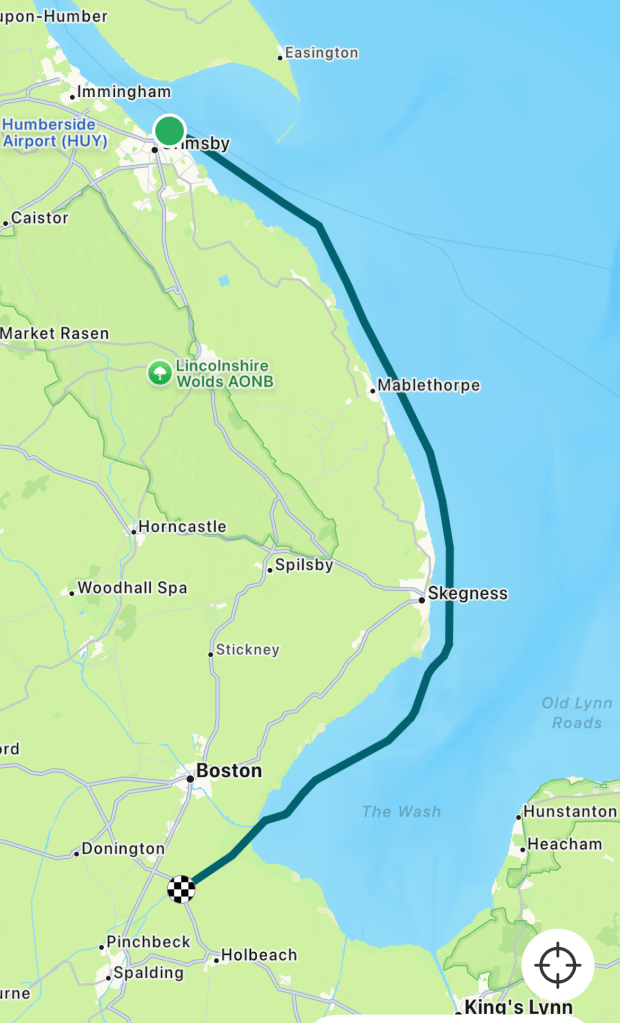

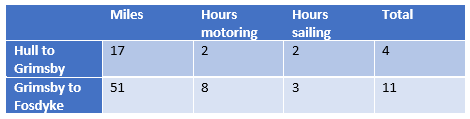

Jeeves, of course, would have approved of a fish supper the night before one of the more complex bits of pilotage yet as we put our brains in gear to head down to The Wash. High Water at our destination – Fosdyke – was at 2030, we were recommended not to arrive more than an hour before – 1930 – and just to pile the pressure on myself I had booked a table at the very popular pub for 2000. Landlubbers with GPS in their cars will not appreciate the skill involved in arriving on time in a boat somewhere 60 miles away across a whole tide with a variable weather forecast, but sailors in the readership can compliment me now, and I think Peter and Tom showed enough respect to be invited back. We locked out of Grimsby with a horde of windfarm boats at 0715…

…motored past what was soon to be the site of a piece of football folklore…

…then various sails were deployed to cruise through a bombing range full of seals (it’s the RAF’s, they don’t work weekends), past Mablethorpe and Skegness…

..and then suddenly we were faced with a wall of sandbanks, agreeing that before GPS and chartplotters were invented this would have been even more unsettling. Luckily it is 2025 so we simply followed the iPad and found ourselves weaving between two walls of sand, simply covered in hundreds of seals, with the excellent names of Old Dog’s Head and New Dog’s Head (the sandbanks, not the seals. Seals don’t have names, silly):

It was at this point that my cunning navigation skills came into play. Simply by asking the iPad what time it thought we were going to arrive, I worked out that we had to slow down, so we took down the mainsail and began rolling up the genoa until we were more or less drifting up The Wash on the tide, between sandbanks miles offshore. This was one of the more unusual, but very rewarding, legs of the trip: the tide was whisking us along ever faster, but we were creeping through the water as slowly as we could, in complete silence. After the bustle of The Humber and all the North East ports this felt very close to nature indeed – and literally was, as we glided past colonies of seals who looked comically astonished at our presence in their backwater. Very few yachts come this way, apparently, since Trinty House took the buoys away.

As the sun gradually set and turned the sandbanks an even deeper orange, we wafted up the River Welland which gradually found itself surrounded by a completely flat marshy landscape, turned ourselves around before the pontoons at Fosdyke to stem the tide and crab down and then across into the free berth. We tied up at 1920, were tidied up and off the boat at 1940, and in the bar ordering Adnams beer from someone with no discernible accent at 1945. Not only had we nailed the arrival time, and had a great day’s sail, we were no longer the least bit North at all.

Leave a comment