I had expected such great things from a short week in Northumberland, and should hastily point out, just in case there are any brothers-in-law reading this post, that it was not the county that let me down but that pesky old weather. I have had a very pleasant week visiting the coastal sites of the far North East, but few of them by boat.

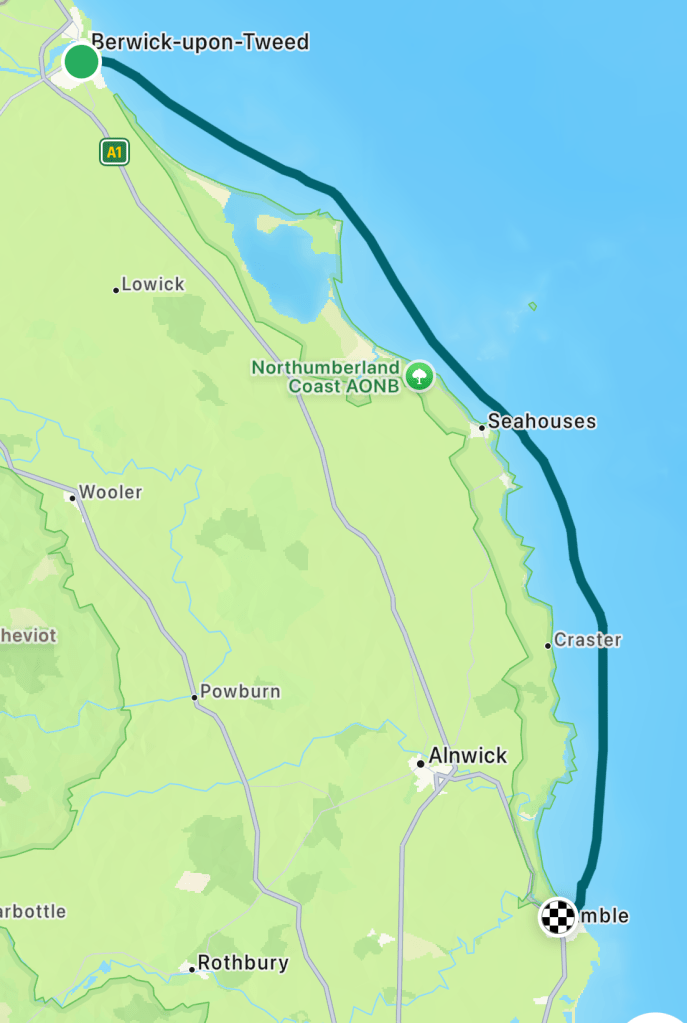

It was all looking so good as Storm Floris howled around my ears in Berwick: he/she was going to blow him/herself out in a day, giving way to very calm westerlies. Ideal! I had pencilled in Lindisfarne, Craster, Amble and Blyth as likely destinations, with the option of replacing the predictable marina at Amble with a more adventurous but supposedly stunning anchorage at Newton Haven instead, and with a nice light offshore wind all of these places were on the cards. Then the next weather forecast arrived – Westerly or South Westerly, quiet for the morning but then Force 4-6. This needed more thought: I had noticed a couple of mentions that the Lindisfarne anchorage was unpleasantly bumpy in a Westerly as the wind comes across the bay when the sands cover at High Water. I was looking forward to playing my lifting keel trump card and hiding in the sheltered bit that dries out, but even this would be exposed if the wind did go into the South West. My caution was confirmed by the friendly harbour staff at Berwick, who sucked their teeth quite demonstrably. “Oh no,” they chorused, “Holy Island can be quite nasty in anything from the West”.

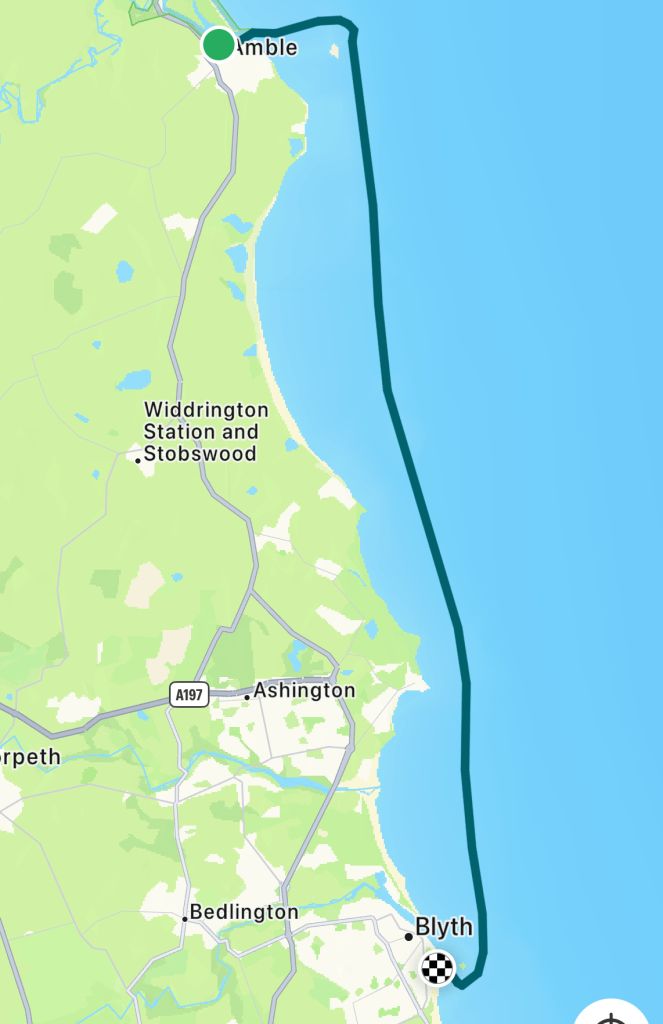

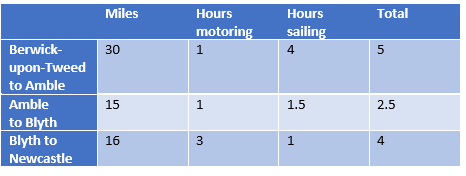

Tough choices lay ahead. Lindisfarne (or Holy Island, as you prefer, but I prefer Lindisfarne as there are lots of Holy Islands) had been in my top ten destinations for years. I’d been before, but like all the others had to leave before the causeway covered, and I was really looking forward to being there on my own boat, regardless of the state of tide. I’d heard tell of the villagers welcoming you rather more authentically, and even of lock-ins in the pub when the tide was high, something I’m sure the famously sociable St Cuthbert would have approved of. That’s a theological in-joke, by the way, he jacked in the relatively mainstream role of Bishop of Lindisfarne after a few years to go and live on one of the smaller Farne Islands as a hermit. But each time I looked at the forecast it looked even more dodgy – the earliest day when it was blowing less than F6 was Friday, which would mean two more days in Berwick, and none at all exploring the rest of the coast, as I had to be in Newcastle on Sunday which meant more or less having to be in in Blyth on Saturday to catch the tide. The tough choice was made. I did not want to be sitting in any of these anchorages in a Force 6, nor much wanting to do any sailing in it, so it was a heavy-hearted skipper that said farewell to Berwick and set a course past all of Lindisfarne, Newton and Craster straight for the softies’ marina in Amble.

Luckily it was a spectacularly excellent sail, or I would have been in tears to get this close to Lindisfarne and not go ashore:

.The sun shone, the spinnaker was up, and I had to admit that there’s no feeling in cruising like worrying a lot about something, taking the tough decision to be a softy, and then not worrying about anything other than what to have for lunch. I made the most of this feeling, with a fine lunch and some even finer views of the sights zooming past.

And zoom they did – having left Berwick mid-morning when the tide was high enough, I was tied up in Amble by mid-afternoon. The sailing was so good I could have carried on all the way to Newcastle, or even Whitby if there’d been time and daylight, but I had my eye on the forecast and also on the ice cream for which, according to my more locally-experienced-by-marriage sister, Amble is famous.

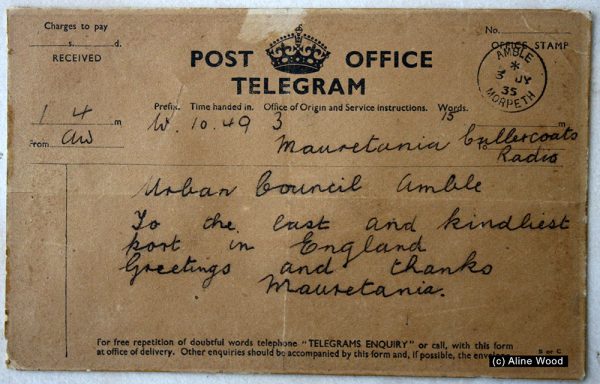

Amble is only famous for two things as far as I know: ice cream is certainly one, it is talked about in hushed tones in both Berwick and Blyth, but more widely as ‘the last and friendliest port in England’. This story I did vaguely know, but it is spelled out on the harbour wall: the Mauretania was sailing past on her way to be broken up in Rosyth, when for some reason the clerk of Amble Council, not even the Harbourmaster, decided to send them a telegram saying “Amble to Mauretania. Greetings from Amble, last port in England, to still the finest ship on the seas”. To which the Captain replied:

This is a lovely story but I have two big beefs with it. First, and most obviously, Amble is by no means the last port in England. As previously discussed, Berwick-upon-Tweed has been in England for about 500 years now, and is most definitely a port rather bigger than Amble was even when it was still a coal loading harbour. Second, notice that the Captain of the Mauretania wrote “the last and kindliest port in England.” This is much more accurate linguistically if not geographically: I’d say Amble Council were being more than friendly, as if they had just waved at a passing ship, they were being kind and sympathetic to the iconic liner on her last voyage, and more importantly their telegram was rather poetic, as was the Captain’s reply. He could have cabled back “you’re not” but chose poetry over pedanty. How sad then, that what passes for a marketing depatment in Amble Town Hall decided that ‘kindliest’ wasn’t going to pull in the ice-cream consuming holiday punters the way ‘friendliest’ would, and blithely (and quite publicly, it was on the information board) went ahead and changed history. Or at least tried to: they had reckoned without the multi-award-winning blog which can now add setting Northumberland history straight to its list of awards.

Moving on before my readership figures dwindle even further, I found Amble both kind and friendly. Someone came to take my lines, and before they’d even finished tying up they’d briefed me on the best pub for food and the best for beer, the best cafe for a greasy breakfast or one where “they do modern things with eggs”, the totally false assertion that the Tesco Express next door was the last place to stock up before Essex, and where to get my hair cut. This last I did actually act on, which gave me an hour in a queue with which I wrote much of the previous blog post. These things take more than an hour, you know, I just did the outline and phoned my agent once or twice.

Not only does Amble indeed house the contender for England’s best ice cream, if not the UK’s (teaser – the real awards will come when I get home), it is pretty well situated for more traditional sight-seeing, which is perhaps why it seems be doing a better job than most of replacing loading coal onto ships by luring well-heeled holidaymakers: hence the rather multi-faceted high street which in an ostensibly Northumbrian coal port setting manages to provide shakshuka alongside greasy spoons and £95 shellfish platters alongside fish and chips. I took advantage of the sight-seeing and the ice cream but not the over-priced fish, knowing that a week of gastronomy lay ahead, and in order to justify the indulgence of two scoops (how can you choose between Sea Buckthorn and Red Crumble Panna Cotta?) walked and cycled to most of the places I’d hoped to sail to.

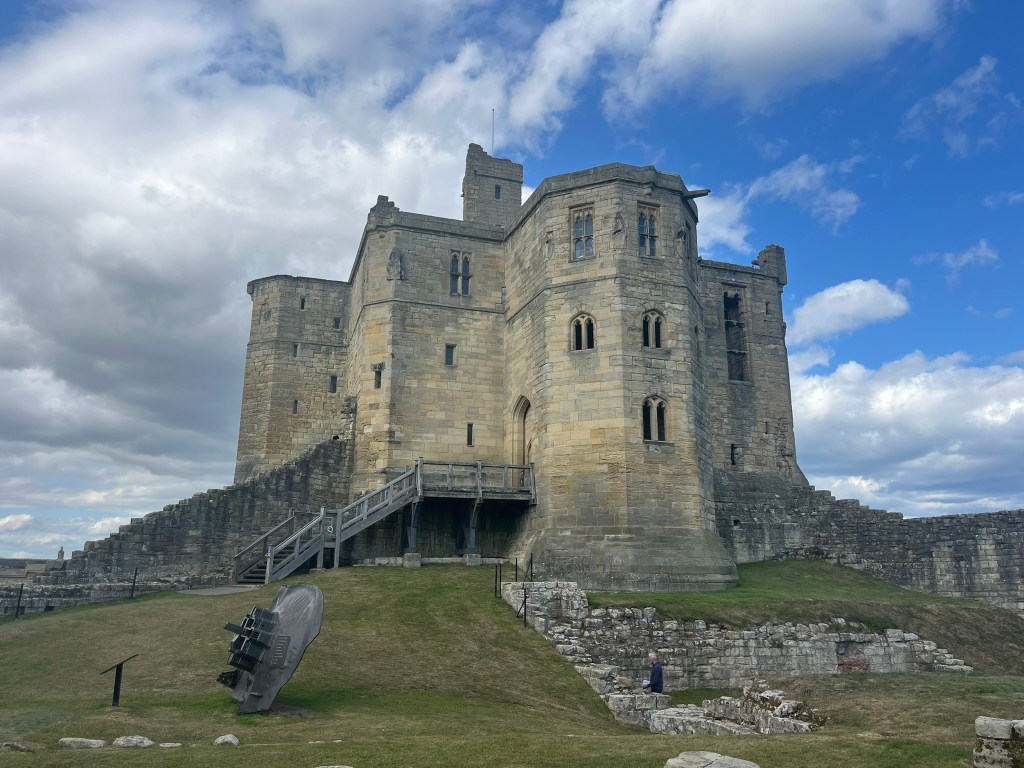

Warkworth Castle isn’t really sailable to unless you have a Topper and don’t mind pulling it over a weir, but it is a pleasant walk up the River Coquet from Amble, and the village is lovely. Incidentally, the man we met in St Andrews, who keep his boat here, turns out not to be as nice as he pretended, having assured three such obviously southern sailors that the river is pronounced ‘Cock-eh’ with a French accent. It isn’t. Thank goodness someone else said it first, or Amble may have turned less kindly.

This was followed by an epic (by my standards) cycle ride to tick two big boxes: the first was Dunstanburgh Castle, which I forgot to photograph zooming past, so here it is up close and even more ruined:

I’d hoped to walk there from the boat moored in Craster harbour, but I’m glad I didn’t try: it turned out to be even tinier and shallower than the pilot had warned…

and anchoring off it among the rocks would have been scary as the wind blew a full Force 6 all day. On the one hand, this cheered me up as I had clearly made the right call to be soft and stay in harbour; on the other, it reminded me that I could work on my fitness before embarking on many more long-ish bike rides. Such physical demands were well worth it, though, if the destination happens to be one of the UK’s most significant temples of gastronomy:

Suitably weighed down with a rucksack of smoked herring, I was grateful for the Force 6 keeping the whiff downwind of me on the way home. Not only did next morning’s breakfast somehow taste better than a Craster Kipper does bought from the fishmonger in Tufnell Park, I also made the valuable discovery, lost on the fishmonger in Tufnell Park, that the ‘a’ in Craster is short, to rhyme with pasta not taster. Chastened by my Coquet experience, I can now also pronounce Cambois and Cowpen as well as Alnwick and Alnmouth. Well, sort of.

The bike ride was stunning though, and let me explore a few more harbours that would have been a bit too exciting in a boat: Boulmer (which is not much more than a beach, a pub and a lifeboat) and Alnmouth which is so far up a beach that it makes Blakeney look like Milford Haven.

The Northumberland Coast is somewhere I’ll have to come back to do justice to. Probably in a car though.

Blyth is less frequented by the Northumberland holidaymaker, but it was high on my must-visit list for two quite different reasons. The first was that my friend Nick, or I should say ‘our friend’ as he is well known to many of the readership, served his curacy here and we visited a few times – most notably for Sarah and I to have a weekend of ‘instruction’ prior to Nick marrying us. I am ashamed to say that I have forgetten the instruction but I do remember the beer, the curry and the organist: she had been made redundant from the pier in Whitley Bay and in spite of being a fabulous player couldn’t read a note of music. Nick had to sing the hymn tunes to her, after which she could reproduce them note for note, albeit with more than a touch of the Wurlitzer about the whole thing. Anyone who has heard Nick sing will be as impressed as I was.

The less niche reason for wanting to visit Blyth again was to be a guest of the Royal Northumberland Yacht Club, which sounds frightfully exclusive and snooty but is famous (even in pilot books) for being even friendlier than all of Amble put together. More importantly, its headquarters are in a lightship so old it’s made of wood, which puts it a cut above the other two yacht clubs in lightships I’ve visited, both of which are metal. Nick had pointed this out to us years ago, when the lightship was surrounded by the skeletons of the coal industry dying before our eyes; now it is surrounded by a wasteland, which is an aesthetic if not economic improvement, and it has its own little marina.

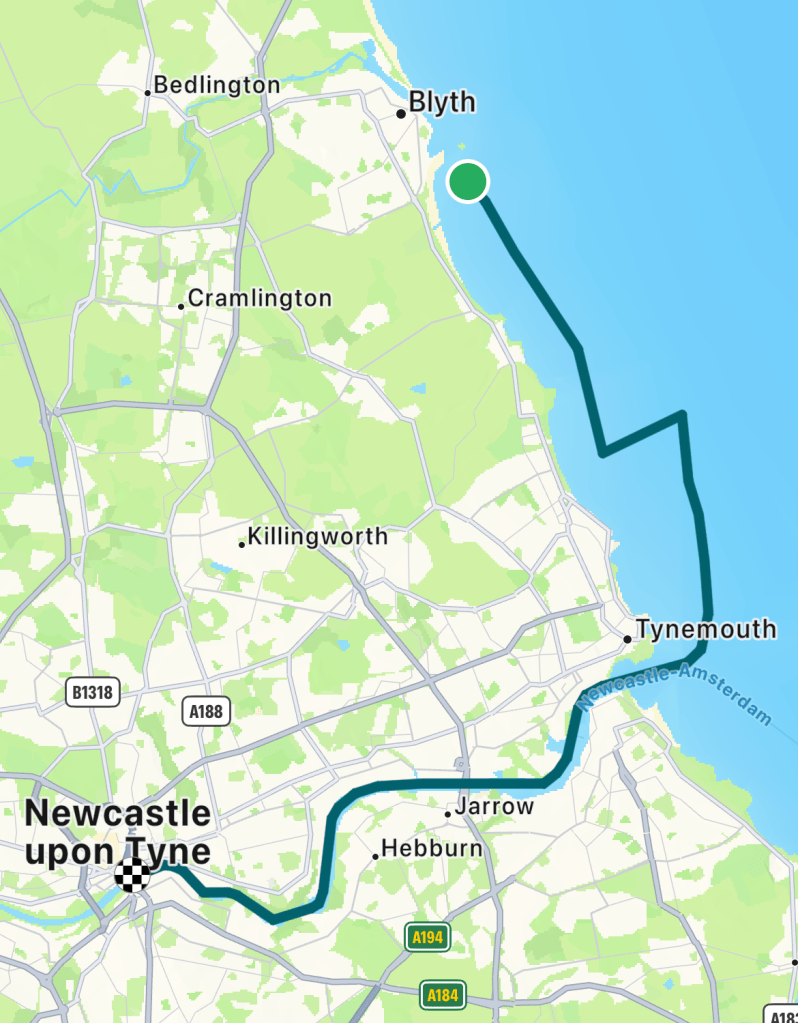

Getting there threatened to be more of a challenge than the night Steve and I drove all the way from Kentish Town starting after work, stopping only for a lock-in in Masham, which is definitely another blog. This time the threat was a weather forecast that was still adding another 15 knots to the forecast each day. This time I had to force myself to be a bit less soft – it was going to gust to 25 knots but being a Westerly it would be flat water. This is why a bought a boat with a tonne of lead at the bottom of its keel. I put on the little jib, took a deep breath and went for it.

Again it was a good thing the sun was shining or I would have turned back. There was a gust of 32 knots just on the way out of the harbour, and aside from one fishing boat on his way back in, the only boats I saw were lifeboats. I separately heard Amble, Craster, Blyth and Cullercoats lifeboats talking to the coastguard, but luckily they didn’t seem to be talking about me. Blue Moon, of course, is made of sterner stuff than her owner, and with three reefs and the skinny jib laughed in the face of 28 knots on the beam, and made it to Blyth pierheads without once going below seven knots. On the one hand, I had to spend half an hour washing all the salt off, but on the other, I could hold my head high as I walked into the lightship to be greeted by some proper sailors who said things like “two hours from Amble? Not bad going. You must need a shower and a beer.” My kind of yacht club, confirmed by meeting someone who was beyond excited to meet someone from the Medway because he had sailed his friend’s boat all the way back from there decades before. The propellor had fallen off at Sheerness but they kept going, taking them even longer to get to Blyth than me and Steve.

My exit from Blyth could not have been more different from my entry: the lifeboats had been replaced by over 20 race boats of every description heading out for the RNYC’s Sunday morning race. The pontoons were teeming, and most people who came by seemed to expect I would be joining them when they saw me changing headsails. They had clearly missed the wind turbine and the dinghy strapped on the deck. I was sorry not to be, as it was one of those perfect racing Sundays, but I had a date with a bridge.

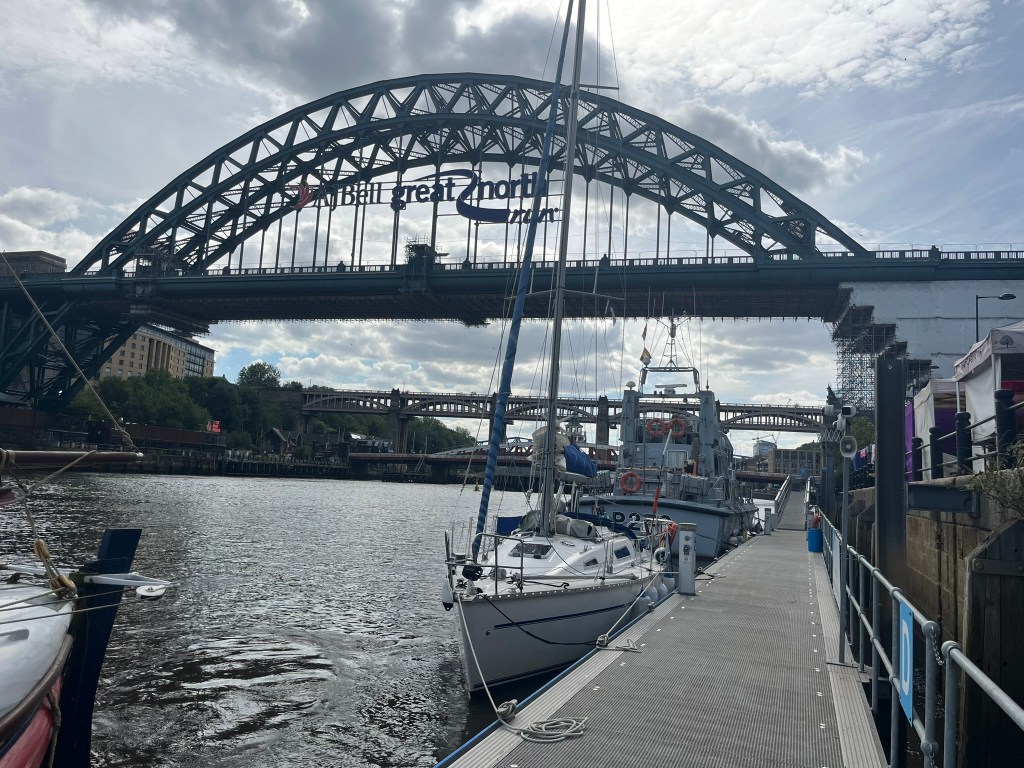

This was the most definite point of the trip so far: I had read about a pontoon in the heart of Newcastle where you could tie up under the Tyne Bridge, and that they would tilt the tilting Millenium Bridge just for one yacht. This was also a must-do, but it was a bit unnerving that you had to book your precise slot weeks in advance, so I was rather focused on being off Gateshead at precisely 1500. My new friends in Blyth had confirmed that you couldn’t miss your slot – one had, and spent the night tied onto a buoy downstream waiting for someone else’s slot so they could go through. I had taken so much trouble to be early that of course I was far too early, which with the kind of fierce flood tide that rivers such as the Tyne tend to have, could be a problem. First I tried slowing down by sailing to windward in five knots of breeze instead of motoring, but this failed when the wind picked up and I had the kind of windshift that would have allowed me to show off to the RNYC fleet behind, so I arrived off Tynemouth half an hour early.

Then I tried waiting to enter the river but when I called the VTS operator and told her my schedule she asked me to follow a big ship which first of all went too fast, then did a handbrake turn in the middle of the river and made me speed up even more so I could steer around it, so I was even earlier.

So it was that I ended up actually drifting up the Tyne, engine in neutral, watching the chartplotter slowly work its projected arrival time out towards 1500. I had assumed that arriving early would be better than late but no, the bridge operator actually called me half an hour before to check I was on time. When I said I was ten minutes early he wasn’t impressed: “just wait ten minutes and we’ll be ready for you at three” he said, clearly an employee of Gateshead Council not the Harbour authority.

I didn’t mind the drifting as I was less likely to hit a tree trunk or a dead dog, and in due course I was swept around the corner just as the bridge began to tilt.

Unfortunately the tilting was accompanied by a very loud blast on the horn, which not only alerted me to the fact that I could now go through, but also approximately a thousand people who were lining both banks of the river to some incoming entertainment. It was a very sunny Sunday afternoon, and the quayside turned out to be the venue for a Sunday market. Just where I was expected to park Blue Moon, in a two knot tide, on my own, in between the beautifully restored wooden Tynemouth Lifeboat and a presumably quite expensive Royal Navy cutter, was a row of stalls selling everything the urban weekend street market crowd expects: fudge, traybakes, hand roasted single origin coffee, prints of Newcastle, bratwurst, Gateshead Gin, T shirts, churros: you get the drift. They all stopped buying the above items to stare at me as I squeezed into the gap. To my intense disappointment, there was no cheering when I tied up comfortably without hitting either the maritime heritage or the defenders of the realm. Perhaps they had got bored watching me ferry-glide sideways at a snail’s pace, terrified of the consequences of one wrong move.

It was 28 degrees, and I forgave myself for sweating a bit. Finally, one stallholder did lean over the rail. “Nice parking” he said, in a tone that suggested he’d seen otherwise on previous Sundays. My day was made, and so was this leg of the tour.

Leave a comment