I’ve known this moment was coming, of course. I have no intention of emigrating to Scotland, so I was always going to cross the border back to England at some point. And, of course, I’ve done it for the last two years but that was different: for a start, I went via Ireland, Wales and the Isle of Man; for another, the Irish Sea makes an invisible sea border between all these places; and more importantly, I knew I’d be coming back. This week, however, I crossed The Border, the one that has the castles and the battles and the legends, the one that you can see and feel the history of, and I’m almost certainly not coming back, not in my own boat, anyway.

I hadn’t wanted to make much of this moment: I’ve noticed quite a few people referring to the blog, even in awards ceremonies, as narrating my sailing trip “around Scotland.” I’m not sailing around Scotland, I’m sailing around the UK, but the fact is that Scotland’s mainland alone makes up around two thirds of the coastline of the UK. If you add in the islands, and why wouldn’t you, since that’s a lot of what I’ve been sailing around, the figure goes over 90% (and also leads you onto internet discussions of the Coastline Paradox, which you may wish to avoid), so it’s inevitable and appropriate that I have spent more time in Scotland than anywhere else.

I had worried about this: the sailing is mainly in deep water, there are lots of rocks and very few facilities outside the main yachting centres, but it has been simply the best cruising I have ever done and a quite special way to see some extraordinary scenery and visit some totally remote and largely inaccessible places. I had worried that the locals would not be totally welcoming to an English yachtsman leading a life of leisure in their hardworking communities, but I have been actively welcomed into every little harbour where fishermen have been friendly, harbourmasters have been helpful and in shops, pubs and cafes people have stopped to chat and ask about the boat and my trip. I’d even worried (and been warned by True Scots) about the state of the Scottish diet once out of the metropolitan gastro-lands of Glasgow and Edinburgh, but even in small village shops there has been a selection of fabulous local produce alongside pubs and food trucks selling seafood fresh off the boat and beer that a Scotsman of the ’70s and ’80s would not recognise.

In short, and with undisguised schmaltz, I have simply loved the place and still can’t quite believe my good fortune in that I have sailed around its entire coastline, more or less, in my own boat, without hitting any of those rocks. The East Coast of England may be my sailing home, but it doesn’t have quite the same allure.

I had assumed that this final parting would create a degree of melancholy in my last few days, and indeed on the train I did catch myself wanting not to get off at Edinburgh but stay on until Stonehaven (it was that train, the one that used to be called The Aberdonian in the not-so-long-ago good old days), but I’m pleased to say that passed within a day, aided by the welcoming, attractive ports I’ve stopped in on the way south, so this is a surprisingly upbeat blog post, which as a result is unlikely to contribute to next year’s awards haul. (Yes, I am beginning to struggle with shoe-horning that topic into every post, but I’ll carry on manfully, you’ll be pleased to hear).

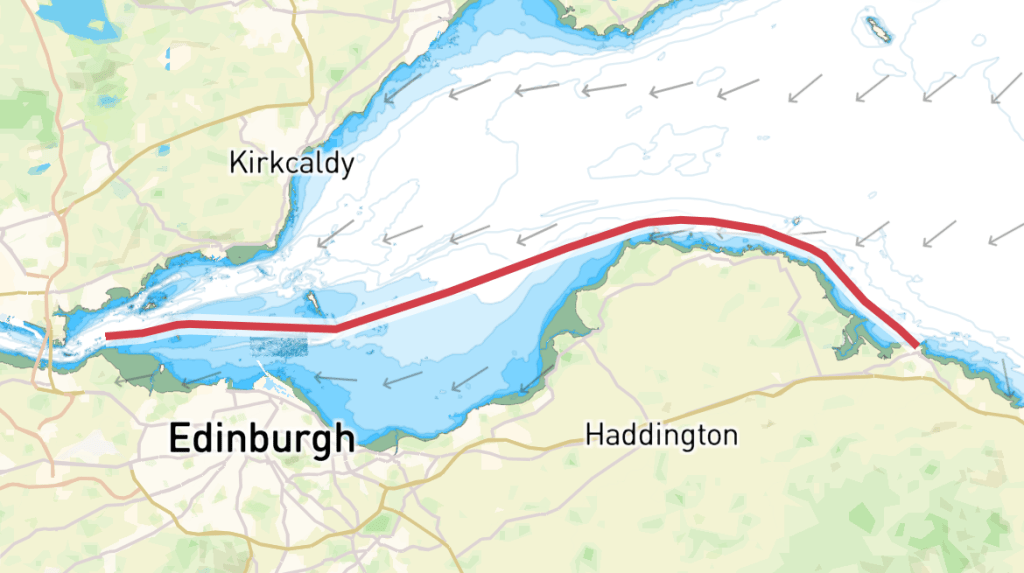

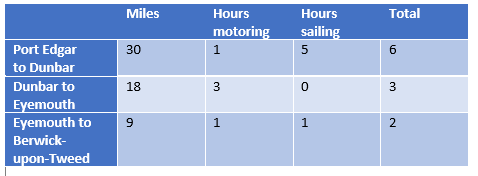

I’ve always found it odd that Edinburgh is so close to England and I probably have a glimmer more appreciation now of how distant London seems from most of the UK, being closer to France than it is to most of its own country. Strangely this closeness seemed more tangible in a boat than the more familiar trip on a speeding train: when you can sail from the capital to the border in a day then you know it’s not far. In an attempt to prolong the experience I had no intention of doing the whole thing in a day though, and I was looking forward to giving my last few Scottish ports a fair hearing, especially since I had spent most of my work journeys with my nose pressed to the train window from Newcastle to Edinburgh rather than tapping away on the laptop, so I wanted to see what this stunning coastline is like when you’re doing less than 100mph.

Dunbar has piqued my interest for a few years: you go through it on the train for starters, and inspection of the pilot book revealed a tiny harbour with a famously tricky entrance between a load of rocks. Suspecting this might be my last chance of rocky bravado before I found myself in muddy England, I’d phoned the harbourmaster who’d said I’d be very welcome as long as I didn’t mind some French people tying up outside me. He said this without a hint of Francophobia, by the way, more as a full description of the welcome on offer.

A very pleasant sail involving famous bridges, spinnakers and views of Edinburgh brought me down to North Berwick, where we had once done the calmest International 14 championship ever and spent most of the week staring at a glassy Firth of Forth and the peculiar Bass Rock, a great lump five miles offshore covered in gannets and their guano. Luckily the wind was also offshore today as the pilot guide genuinely states that in fog you can navigate your way around it by smell.

Another peculiar feature of this coast is that by default the waves seem to come from the north regardless of what the wind is doing. Dunbar harbour entrance faces west, and the wind was from the south, so I’d assumed all would be well and didn’t need to worry about the same pilot warning that the entrance would be dangerous in northerlies. Today it wasn’t dangerous per se but it was certainly enough to push the heart rate to levels that would have exposed any underlying health conditions. The northerly swell got bigger and bigger as I headed through the rocks towards the beach, in spite of the wind blowing all of five knots the other way. On the one hand I wanted to slow down to play safe, on the other I quickly realised that unless I floored the throttle I would miss the tiny gap in the rocky cliffs that passes for a harbour entrance.

The presence of half a dozen lads with fishing rods who were clearly looking forward to a spectacle they’d seen a few times before did nothing to calm the nerves. A litre of diesel in about ten seconds and I was through into the relative calm of the tiny harbour, with the simple task of spinning on a sixpence to come alongside a rough wall under the watchful gaze of the harbourmaster, his assistant and their dog seeming an absolute doddle in comparison.

Dunbar Harbour ticks the picture postcard boxes but for a restful night’s sleep I won’t be hasting back: in spite of the harbourmaster’s guarantee that the southerly wind would stop the swell within a few hours, it surged through that tiny gap all night, and all the boats in the harboured surged up and down with it, except for the two visitors and the lifeboat, who being side on rolled from side to side.

The chatty French couple who tied up outside me were planning on catching the train to Edinburgh next day for some sightseeing and I could hear them debating the wisdom of leaving the boat here all day. Or I think that’s what they were saying, they could have been comparing Baudelaire with Burns, my French has on occasion let me down when not in a restaurant or bakery. To top it all, the walls of the ruined castle are now home to a protected colony of kittiwakes, who look and sound to all intents and purposes like large gulls, who squawked all night and smelled much as I imagine Bass Rock to smell.

I was quite pleased to come up with the excuse of leaving early next morning purely so that my neighbours could let me out and catch a train, and the swell had not reduced one bit as I floored the throttle again in a departure that felt like Hawaii Five Oh with rocks. Younger readers make need to Google that reference, while readers of any age may enjoy this clip of my exploits here; it is even better with the sound on.

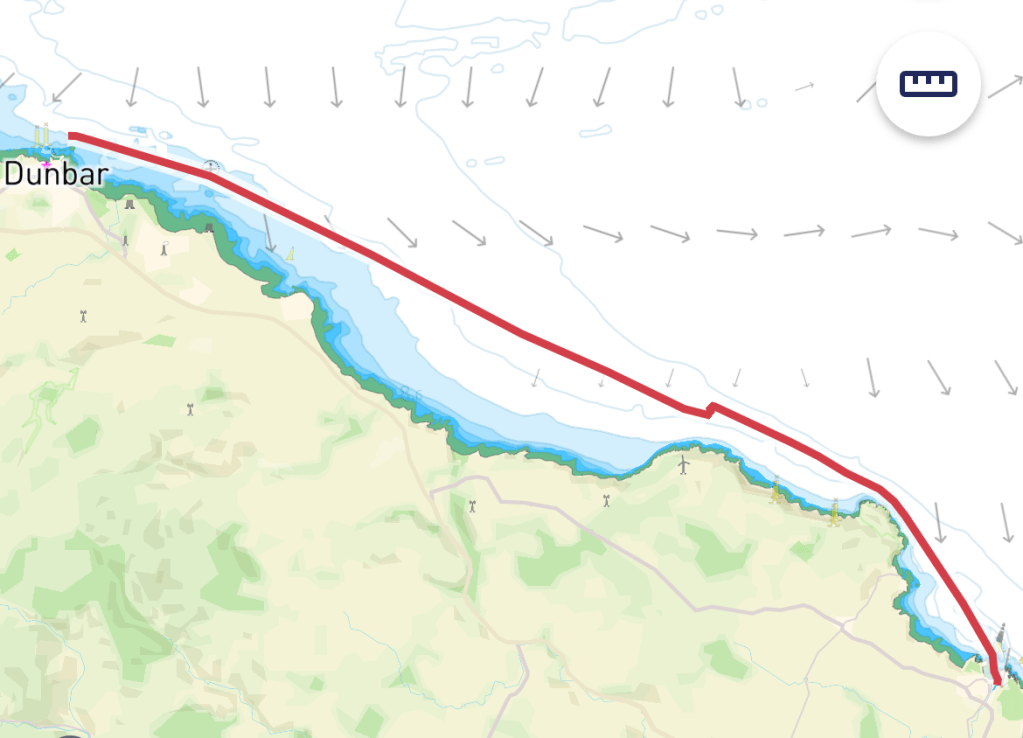

The early start made for a couple of hours leisurely motoring in a flat calm which took me past St Abb’s Head, which should really be the border as it’s where the coast of the Firth of Forth turns south and heads down to England. But it isn’t, and a few miles further south is the most Scottish fishing town in the shape of Eyemouth, which I’d barely heard of, it not being visible through the train window. The whole area was full of stunning cliffs with seabirds wheeling around, and in the calm I managed to motor close enough to decide that since Storm Floris was booked to spoil my sailing in a couple of a days time, these cliffs would do for the full land-based storm experience.

Eyemouth is well up on my pleasant surprise list: it had mixed reviews from passing yachts but I did notice that the more recent the review the more positive it was, and it was clear from the moment that I phoned the harbourmaster that there’d been a strategic decision to be nice to visiting sailors. I got clear advice on how to negotiate their almost-as-narrow-but-not-the-least-bit-tricky entrance, an exact spot to tie up on their very new and very sheltered pontoon, and a personal welcome which included the offer of a tour of the harbour. Best of all, I was told, learning that it was my last night in Scotland, they had laid on the fireworks for me and the harbour would be closed from 2230 to host the rockets.

This wasn’t entirely true: the fireworks were the culmination of a week of celebrations for the crowning of the Eyemouth Herring Queen. This is a surprisingly modern tradition, apparently cooked up between the World Wars to reinvigorate the herring industry decimated in WW1. It wasn’t entirely successful as a bargaining chip in the fish quota wars, and the harbour now has as many wind farm boats and yachts as it does working fishing boats, but it certainly seems to have given the town something to pin a community spirit on: there was a whole week of events with three or four different things happening each day.

This wasn’t some ghastly May-Queen-meets-beauty-pageant, everyone clearly took it very seriously: the candidates have to submit CVs and essays and a shortlist are interviewed by a panel of local worthies about their aspirations for the town. Once the week of festivities is over the ‘lucky’ winner spends the rest of the year going to civic events, charity dos, fundraisers and representing Eyemouth at trade shows and the like – all while still studying for their Highers (I think – Scottish education is still a mystery). But their reward is that for years to come their teenage picture will be hung on lamposts all over town once a year…

…and they even get to put up a plaque on their house celebrating their big day all those years ago:

Pubs, cafes, shops and even just houses had windows plastered with signs wishing Grace, this year’s Queen, good luck. I couldn’t help thinking how much she was going to need it.

The fireworks were excellent, coming at the end of a sunny day in which the entire town and most of their visitors crammed onto the tiny beach and into the tinier funfair which was itself crammed into the even tinier car park outside the Co-op. In the absence of herring, Eyemouth seems to have discovered the value in offering chalets to holidaying Geordies, judging by the accents around the harbour and in the queue for the ice cream. Eyemouth delivered here as well, laying on for my last night my favourite Scottish beer (Fyne Ales’ Jarl, since you ask), my favourite Scottish supper (a real contender for the UK’s top fish and chips) and my favourite Scottish treat (the Giacopazzi family brought the ice cream recipes with them from Italy but cottoned on to fish and chips pretty quickly too in a piece of multi-skilling that seems to be repeated all down the Scottish East Coast). As a last day north of the border, it couldn’t really have been improved on.

I would have loved to stay in Eyemouth, but the unseasonable Storm Floris was due in a day and I needed to start heading south. As if to tempt the melancholy, the weather had arranged for it to be wet and fairly windy the following morning, which at least meant that the short trip to Berwick-upon-Tweed passed quickly in a blur of rain and pot buoys. I’d been told that the Scottish Government had really clamped down on marking pot buoys, and it was true that all over Scotland they were impressively large and well-flagged, unlike the milk cartons around the South West Coast of England. It sounds improbable but it seemed that the moment we crossed the border the flags disappeared, and within minutes I had hooked a buoy lurking under the surface. I furled the genoa and managed to get the boat back enough to release the buoy, but this was harder work than last week with three of us and not much wind. I set off again, keeping even more of a lookout, and was within sight of Berwick pier heads when we suddenly stopped dead.

To my horror, a pair of buoys which were easily 20 metres away were heading towards us, with a huge bight of floating rope now wrapped around the keel. This required all the sails down and a degree of effort not to panic: it was windy but at least the wind was offshore. I heaved and pulled and tried to move the buoys one way and then another but nothing doing: it was time for the safety knife. It cut the rope instantly and to my relief the heavy end with the creels attached disappeared immediately leaving me holding the floating buoys. I felt bad about cutting away someone’s valuable equipment but furious that they’d set it with such slack rope, in every sense of the word – it was high tide so no excuse for any slack at all, let alone 20+ metres of it. To my horror, though, the rope bounced back to the surface with a huge coil loosely tied, and dozens more metres lying on the water. I couldn’t leave that for someone else to get wrapped up in so I motored back, picked it up with the boathook and tied the buoys back on. Having spent a good twenty minutes doing all of this, I am still regretting not acting on my instinct to spend twenty seconds running downstairs to fetch a marker pen with which to write a choice four-letter word on the buoy.

After this effort Berwick seemed a very welcome place, even in the rain, and unlike Eyemouth almost devoid of marine action. The equally friendly but not so present Harbourmaster had texted me (in his defence, it was the weekend) to say I’d be welcome to stay as long as I didn’t mind rafting up onto their pilot boat. He assured me they wouldn’t need it that week, which gives you an indication of how busy the Port of Berwick isn’t, and I was the only boat I saw moving until I left three days later.

The pilot boat was clean and easy to come alongside, and better still it was only two minutes walk from the cafe reputed by the internet to serve the best breakfast in the North East. This sounded like quite a high bar from what I know of the North East, and I very rarely eat breakfast out, but after the pot buoys I felt I’d earned it. It was a brilliant example of the Borders: everyone in the cafe was English, they were reading English Sunday papers and the radio was playing Radio One, but the breakfast was called The Big Yin; it had hash browns, tomatoes and baked beans which, being vegetables, I’d barely seen in Scotland, alongside haggis and black pudding and tattie scones. Like Berwick itself, it was English but only just.

It was a Sunday and most of the quirky shops that apparently make Berwick such an attraction were closed, so I tried to do some very English things: I wandered around the largely intact fortified walls built by Elizabeth I but which turned out to be a sort of Tudor HS2 in that the Act of Union was signed ten years after they were finished at vast expense; I marvelled at the bridges but the old one was built by James I (VI of Scotland, don’t forget)…

…and the extraordinary Victorian railway viaduct was built by – you know who – one of the Scottish Lighthouse Stephensons.

I walked out to the end of the pier and everyone on it was Scottish.

Finally, an entirely English opportunity presented itself: Evensong. A sunny summer’s evening, long shadows in the churchyard, a congregation of ten of whom I was the youngest, a choir who insisted on singing an anthem clearly out of their comfort zone, and a properly posh Vicar who stood outside afterwards and enquired, apparently in all sincerity, whether I was one of his regulars. This was no Calvinist kirk, this was the good old Church of England, and I really was home.

Then I went and spoiled it all: I went back to Scotland. On the bus.

I’d spent a day stormbound – literally, as Storm Floris had Blue Moon pinned to the side of the pilot boat, and even in the sheltered Tweed Dock we recorded gusts of 46 knots. The harbour guys kindly came down to check I was OK and lent me their biggest fender, so I thought it was unseamanlike just to push off and go sightseeing. So when the following day turned out to be just plain very windy rather than an actual storm, I got on the bus to St Abbs (the village doesn’t have an apostrophe) and hiked around the lighthouse and the headland (which does), back along the coast path through Eyemouth to the picture postcard village of Burnmouth which is, reassuringly, at the mouth of a burn but one that looks more like a canyon as the train hurtles over the top.

All of this was lovely, and had some excellent views: of St Abbs, a fishing village that most of Cornwall would kill to look like (and I suspect a few Edinburghers have holiday homes in)…

…of the lighthouse I’d motored around on a much calmer day…

…of glorious beaches in rocky coves…

…of Eyemouth harbour from a different angle…

…

…of Burnmouth at the bottom of its canyon…

…and, best of all, of what the Berwick harbourmaster assures me is the world’s largest mobile surveying platform which had been held up on its voyage by Storm Floris and forced to take shelter just off the Berwickshire coast:

So I caught the bus back to Berwick footsore, sunburned and happy, but also feeling like a tourist who had popped over the border for the day.

I will be back, perhaps not in haste because I could do with going somewhere warmer next year, but after three summers I like Scotland even more than I did three years ago, which was already quite a lot, but now I will always be an English tourist and I’ll have the same predictable encounters with the country and its people that every tourist has. I’m sure the country will be as beautiful and the people will be as welcoming, but it can’t possibly be as interesting or as much fun as sailing around it has been.

Appendix

It doesn’t really fit the narrative but members of the Parker & Seal Sailing Association are understandably tickled by antics involving actual seals, so they would be mortified if I missed out the discovery that Eyemouth has three tame seals that never leave the harbour because all their wants are provided by tourists who can buy bits of fish at extortionate prices from the fish van, then feed them to the seals by hand:

Leave a comment