Enough alliteration I think, it is becoming a burden.

Dear, devoted readers (and students of blog-writing who have been sent here by their professors of bloggery to see how to win awards at this game) might peel back the months of subsequent entertainment to remember that last year I spent a whole week in the Moray Firth (An excess of leisure) failing to get to a mystical place called Findhorn, which has occupied a place in my imagination for many years at the absolute opposite end of the spectrum from Kinlochbervie and Grimsby, being as it is (or rather, in my case until last week, was rumoured to be) not an industrial fishing port with smelly showers but a rather chi-chi village close enough to Inverness to support a thriving yacht club famous for its association with the National 18 dinghy class, which is what my parents competed in and I learned to sail in. The good news is that you can now stop feeling sorry for me because I have ticked that box too, along with a couple of others, and whilst Findhorn may no longer smell of fish it seems to have locals every bit as friendly as fisherfolk but rather easier to understand.

Another box ticked was getting two of my very oldest friends to come sailing with me (by which I mean of course friends who, whilst indeed are even older than I am, I have known longer than all but one of my other friends. Keep up.). Sadly, these friends are so old and important and so in demand that they could only spare a long weekend, which made their commitment even more commendable as it involved spending an entire day travelling to get here and another one getting home, turning a long weekend into a week with no extra sailing. As a result I felt the need to deliver, and when your boat is in Wick and it is forecast to rain quite a bit and blow from the south, that seemed as if it could be a challenge too far, especially since they had got up at 0500 to get to Inverness by breakfast time only to wait until mid-morning for me, then until early afternoon for the train which took until early evening to get to Wick. It is an extraordinary journey: the line was built by the infamous Duke of Sutherland largely to service his shooting estates on the way to the herring ports so it wanders inland through barren moorland and mountains which, whilst spectacular, are not anywhere near the rhumb line to either Thurso or Wick. The harbourmaster tells me you can drive it in two hours on a good day but the train takes nearly five. Hats off to David and Philip for agreeing to such a trip, or perhaps you hadn’t realised what you had agreed to.

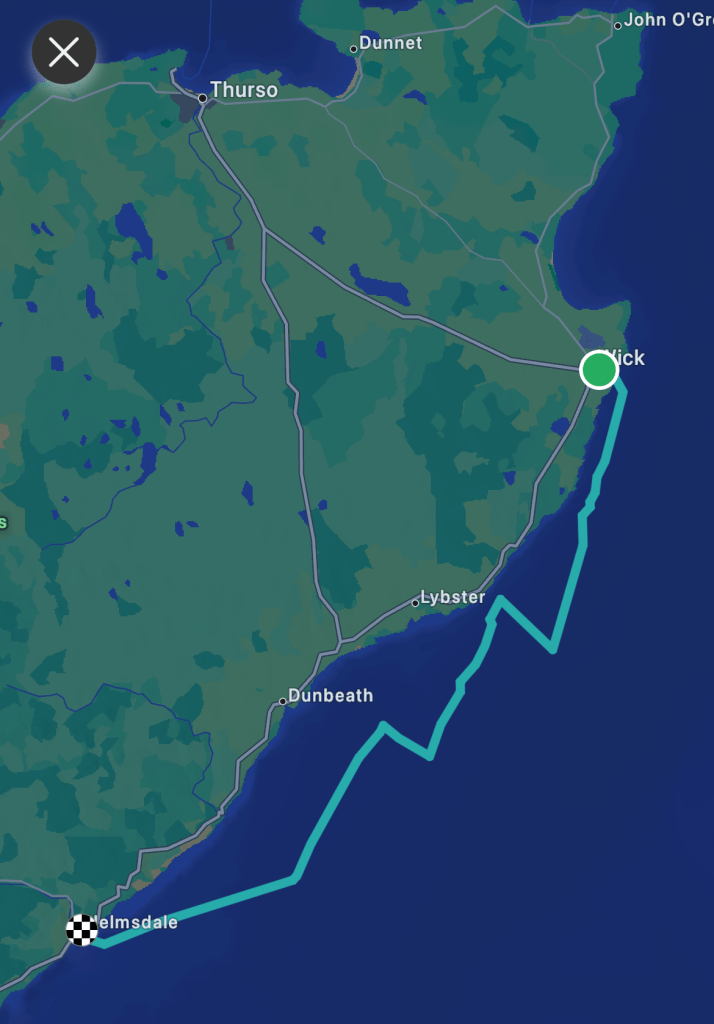

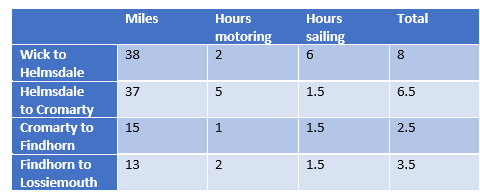

A damp evening in Wick followed by a damp walk to a Co-op being rebuilt under scaffolding and the most disappointingly awful bakery somehow managed not to dampen the spirits, and by mid-morning we were on our way south to Helmsdale, the three of us in the same boat for possibly the first time in about 50 years.

Sensing an opportunity to catch three old codgers out, the weather had not only arranged for it to be moderately windy, it also thought it would be quite fun to intersperse these quite spicy gusts with periods of near-calm, meaning that while David and Philip took turns to steer, I literally showed them the ropes as I put in a range of reefs and took them all out again several times an hour for the rest of the day. In the interests of fairness, the tide then joined in by spoiling their day too and running against the wind to create the nastiest sloppy waves any of us had ever seen. At least that was our excuse for the exceedingly slow progress, and the planned afternoon of herring-based sightseeing followed by a sharpener or two in a nice pub and then fish and chips from “The North’s Premier Restaurant”‘s takeaway hatch was turning into the very real prospect of the chip shop shutting, so I shocked them both by turning on the engine and motoring hard directly upwind for an hour.

This scandalous behavior did at least mean an arrival during opening hours, and Helmsdale was exactly as I remembered it, (Silver Darlings and a Royal fish supper) although rather less remarkable without King Charles in town. My guests hid their disappointment well even though it was sufficiently damp to require our beer to be drunk in a bar quite unlike the Royal Yacht Squadron or even the Medway Yacht Club: no-one was wearing a blazer, and the only other customer entertained us not with yachting stories but jokes involving the name of the beer (Sheepshaggers Gold) and supporters of Aberdeen Football Club. Apparently the two are connected, although we only understood around a third of what he said on the subject on account of not only his accent but also his lack of teeth. Things took a turn for the better when we decided to eat our fish supper indoors out of the rain, and found that not only had the proprietor framed the picture on my blog of him shaking hands with the King (disclosure – I nicked it from his Facebook page), he was even wearing the same checked shirt.

Things improved the following morning: Donald the friendly harbourmaster came to say hello even though it was his day off, and the wind decided to be as friendly by turning 180° and dropping. David excelled in his new fraternising-with-fishing-folk skills by negotiating the loan of their water supply in return for a mere ten minutes humping crates of live shellfish, and as soon as he’d finished we were off south once more. My rope demonstration was restricted to the spinnaker halyard, the toffee crisp slices from the dreadful bakery were not quite as bad as they looked, a passage of over 20 miles gave me an excuse for a fried breakfast and all was set fair.

Then the wind dropped, and stayed dropped. The spinnaker dropped too, and so did the mood. We were resigned to a day of motoring in a glassy calm, past some really rather weird features. First (I say first, it was after lunch, that’s how dull the day of motoring was), the peculiarity that is Tarbat Ness, the strangely thin spike of land that separates the lovely but shallow Dornoch Firth from the lovely and very deep Cromarty Firth, making the sinister-sounding but rather lovely Black Isle.

The second was the weirdness that is the entrance to Cromarty Firth, which felt a bit like the gates of a maritime Mordor: two huge and almost perfectly symmetrical cliffs framing a narrow channel into a huge but low-lying firth beyond.

The firth is beautiful and surrounded by woods and fields, but anchored all the way down it are oil rigs and cruise ships, queuing up to be repaired it would seem.

All of which is in the most stark contrast to the town of Cromarty itself. I’d wanted to visit it probably just because it gives its name to an area in the shipping forecast (“Cromarty, Forth, Tyne, Dogger: Easterly seven backing North-easterly gale eight, showers later, good”) but comments on various pilot guides suggested it was a nice enough wee town, so we picked up a visitors mooring and dinghied in to the improbably small harbour with no great expectation.

Wrong. Cromarty is a strong contender for the most pleasant surprise of the trip. I’ve been to plenty of places that are as nice or even nicer than described, and a fair few that are less so, but to none that are barely mentioned in pilot books but turn to be extraordinarily attractive. Cromarty makes Aldeburgh look like Gravesend, being made up of several streets of beautifully-maintained Georgian merchant houses and fishermen’s cottages. A short-ish drive from Inverness it has clearly been discovered by the well-heeled of that city, so it has all manner of city-dwellers’ ideas of what a country town should have: an artisan bakery, an organic greengrocers, not one but two arts centres, several galleries, gastropubs and the smallest cinema I have ever seen that wasn’t on wheels:

I’m afraid I am an incurable property pornographer, and wandered around drooling. No matter that I don’t have any possible reason or wherewithal ever to live here, I want them all.

Fortunately the estate agents were closed and I was dragged away from the RightMove app by my sensible friends who already have nice houses in the country, and was forced to eat a very nice pie and drink some very nice beer in the very nice pub where everyone seemed to know and like everyone else and were probably discussing the latest community arts project or coastal rowing regatta or family picnic and litter-pick.

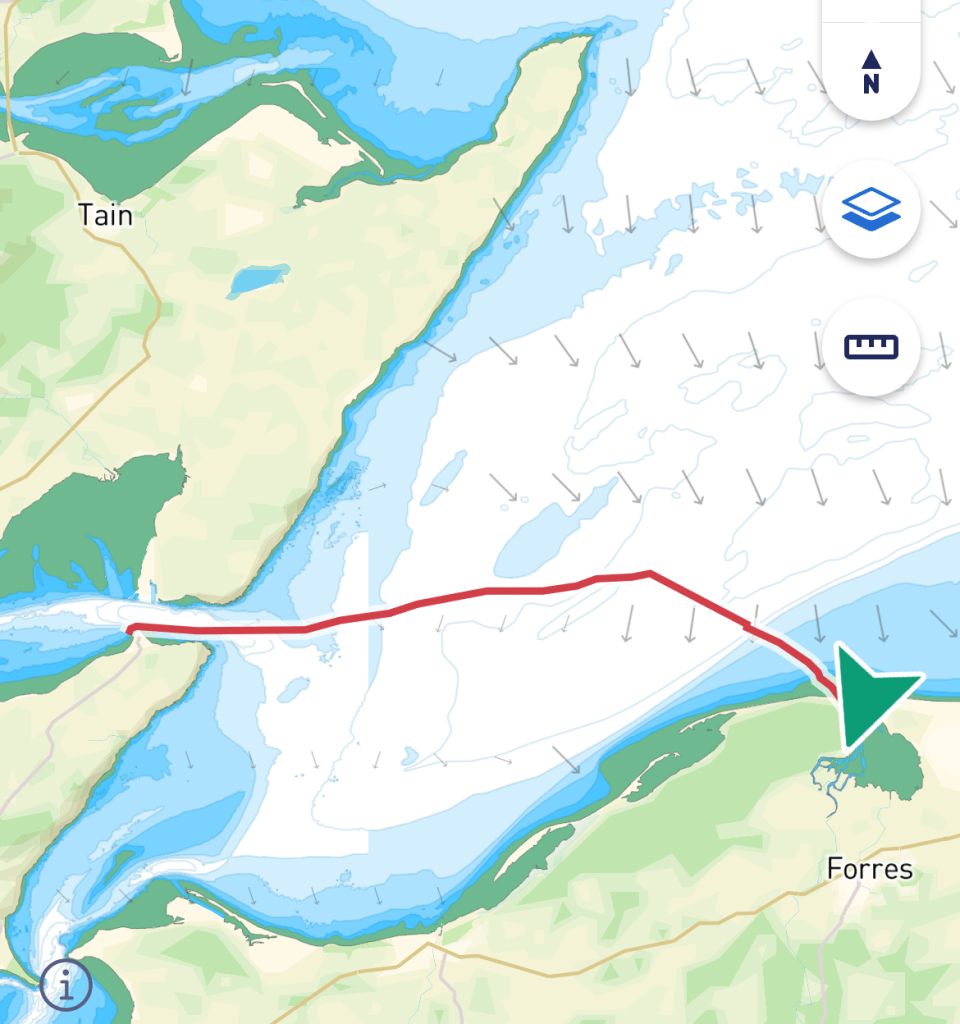

Cromarty proved to be a an excellent staging post en route to Findhorn, not just geographically but demographically: after the rugged deep-water wilds of the West and North I was about to enter a proper river estuary with a Royal yacht club in it for the first time since Birkenhead, and that’s a sentence I never expected to write. The difference is that the River Findhorn is on the East Coast, and like so many other East Coast rivers has a sand bar at the entrance.

I am fine with sand bars, although I’m more familiar with ones on the rather cushier part of the East Coast, but Findhorn’s is particularly tricky: it has all sorts of warnings in the pilot books and a four-page instruction booklet you can download from the Royal Findhorn YC website which, whilst quite explicit about the very shallow sand banks and how to avoid them, was strangely quiet on the subject of how deep the entrance actually was, containing just the mystifying phrase “2Hrs before HW all the sand will be covered and there will be at least 5ft of water even on a neap tide”. We decimal types had worked out that our 1.88m boat would need over six feet – what about us? We had decided to err on the side of caution and wait until one hour before High Water, which still meant leaving Cromarty at 0630 to get there on time, and we didn’t want to be early.

Since there wasn’t much wind we put the spinnaker up to make sure we weren’t late, but of course as soon as the wind saw us do this it called our bluff by going up to 15 knots, then 18. David was determined to show off his downwind helming skills and we were roaring along at 7 to 8 knots.

Unfortunately this did have the effect of getting us there a bit early, just in time for the wind finally to go above 20 knots, so the sails came down and we found ourselves motoring for a red buoy as instructed, surrounded by waves breaking on sandbanks left and right. David steered us in as the depth dropped and my finger got very nervous on the keel up button. 2.5, 2.4, 2.3… surely it couldn’t be this shallow? 2.2… past the buoy and we were in, with an indulgent 3.5 metres all the way up to the sand dunes in the distance, but only if we kept close enough to the waves breaking on the sandbank to windward that we could have jumped out and built a few sandcastles.

We slowly got our breath back, negotiated the last few bends and the tide that was still running at over two knots, picked up a visitors mooring off the yacht club, patted ourselves on the back, cooked a massive celebratory breakfast and began to drink in our surroundings. We were in the most extraordinary place to sail: sandy shoreline and woods all around on one side, dunes and broad flat beaches on the other, and in the middle a sheltered but very shallow river estuary. We could hear the waves roaring from behind the dunes but here the water was flat and there were rows of moorings containing, amongst other things, a Dragon and a National 18, which really did make us feel at home. It was Cadet Week at the RFYC and there were dinghies being prepared for racing and RIBs pottering about. It all felt very familiar, but looked as different as could be from any of the East Coast Rivers we grew up sailing on.

We dinghied ashore and made our way to the club where we were welcomed by a rather surprised Commodore; it felt as if visitors weren’t that common and after our experience earlier we could see why. She was suitably impressed that we were from the Medway and even more so that we had brought our own Vice-Commodore with us, and within minutes she and Philip were deep in conversation comparing notes on subscriptions and building maintenance, such is the glamorous job of being a yacht club commodore, while slowly the club filled with kids getting ready for their racing.

Findhorn village was the opposite of Cromarty in that it was exactly as expected: small, charming, and obviously full of holiday homes. The cars were large and new, the cafes were full and sold only organic cola from Dalston, the beach huts were freshly built and for sale to those who felt a second home in the village wasn’t enough, and a steady stream of 4x4s announced the arrival of Findhorn families for their sailing week. We walked on the beach which would shortly again have those scary waves racing across it…

…and ate a very nice meal in a pub which wouldn’t have disgraced Dartmouth or Woodbridge, crowded with a suspiciously high proportion of English voices which would have sounded at home in both of those places.

It was all very lovely and we were very happy to be there: I was particularly pleased to have ticked that mystical Findhorn box. But most things mystical become less so when you’re standing in them and that was the case with Findhorn: after the wilds of the North and West I felt I had stepped over that sand bar back into a completely familiar world.

Now I am off to places like Peterhead, Fraserburgh and Stonehaven: hard-working East Coast fishing ports on a harsh coast. I suspect I may be about to step back out of the familiar for a bit and into a world that is different again.

Leave a comment