You’ll be pleased to hear that I am now out of the Land that Thomas Telford Built and back on the West Coast where nature did his job for him by creating sheltering islands and safe natural harbours wherever you look. However, to get there we had one final piece of Telfordery to negotiate and it’s probably his finest: the Caledonian Canal. Finer even than the Birmingham New Main Line or Smethwick Galton Bridge, and with rather more impressive scenery.

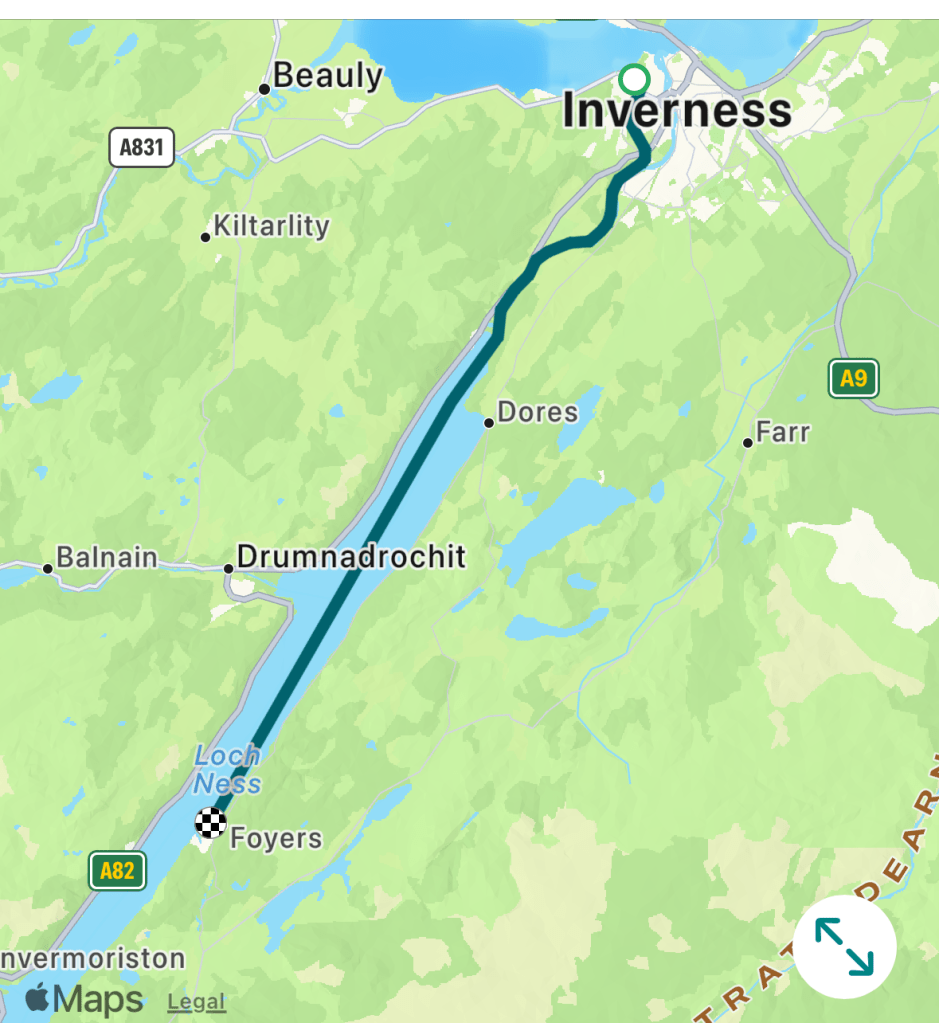

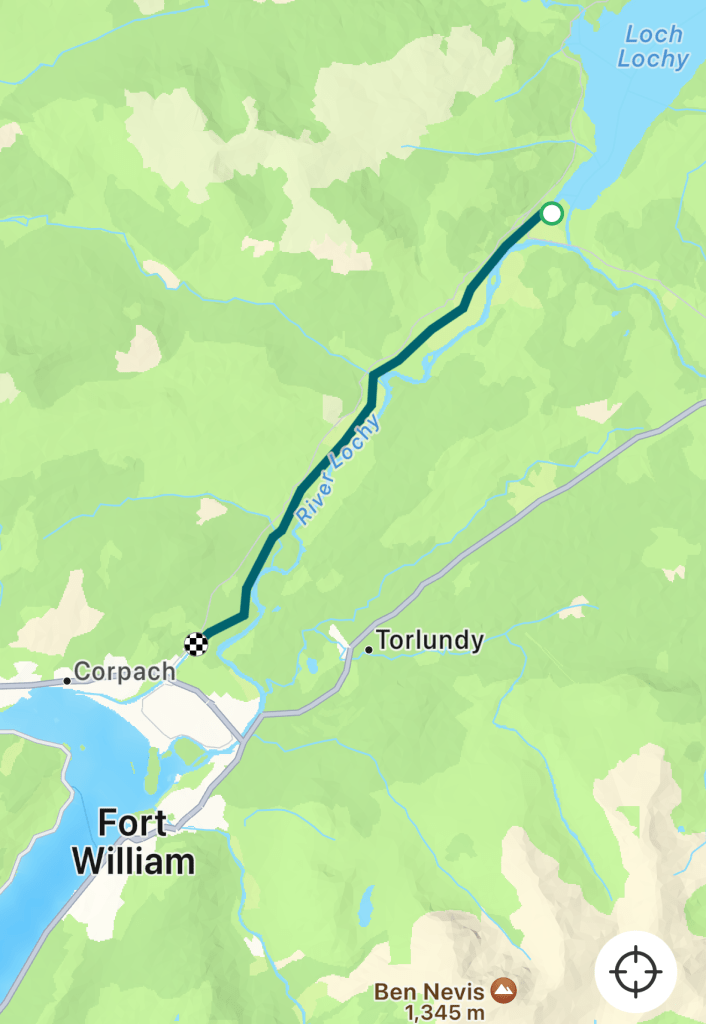

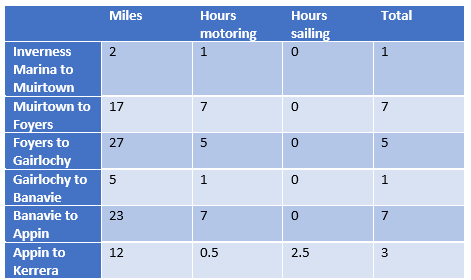

The canal had been on my to-do list for decades, ever since Sarah and I had gone on a hike up its towpath in the middle of nowhere and came round a corner to find a gaggle of large sailing yachts with their masts up motoring through the mountains. Not that it has many corners: it follows the Great Glen in a more or less straight line from Inverness down to Fort William, 60 miles in total of which only 20 is man-made because he cunningly joined up various lochs along the way, most notably Loch Ness and the brilliantly-named Lochs Lochy and Oich. Why is there not a Lake Lakey in the Lake District?

Sailing in your own boat down Loch Ness just feels like a must-do, and with the added enjoyment of being on the other end of the tourist camera lens it was probably the biggest win of adding a year to the journey. Many circumnavigations of the UK go through the canal, thereby annoying Scots who understandably feel that missing out a quarter of their land mass is cheating, so I am very lucky to be able to sail around the top and back through the Caledonian Canal one year and around Orkney and Shetland the next.

It’s not impossible to go through single-handed (we saw one very competent example, but it involved a lot of complicated ropework and some help from the lock keepers) but it’s a lot easier and more fun with friends, so I was pleased to be joined by Marnie (who was going to come with Sarah until the prop seal incident changed the dates) and Andrew (who benefitted from the changed dates to squeeze the trip into his hectic regatta schedule), and we duly convened on Tuesday afternoon at Muirtown Basin on the edge of Inverness in time to walk down and survey the sea lock at Clachnaharry which I’d come through the day before, sticking out into the mudflats of the Beuly Firth like one of those dams we used to build on the beach when the boys were little. (Actually the real reason was to go to the cosy Clachnaharry Inn, but it was nice for everyone to begin at the beginning, as it were).

It’s all run very well with a good combination of efficiency and friendliness. All the lock-keepers had seen boats even less experienced than us, and all were clearly there to ensure their customers enjoyed their holiday, which I am afraid to say (see previous post) is very much what it felt like. At 0920 next morning all the boats booked in for the 0930 flight of locks were called on the radio and invited to present themselves at the swing bridge in five minutes time. We did, were met by a team of lock keepers who took lines and gave us a briefing on what to do in staircases and single locks, and we were off.

The Skipper’s Guide warns you not to rush but we did have a bit of a schedule: Marnie had to catch Saturday morning’s train (thank you Scotrail for yet again cutting off the West Coast on a Sunday) and Andrew and I had a date with Ben Nevis. But from the moment you lock in you are at the mercy of the lock-keepers who are efficient and courteous but take their lunch breaks very seriously. They also have an eye for the so-called rush hours, which gave us an excuse for a leisurely breakfast more than once, including Day One with our 0930 departure. Most of the locks are grouped into flights which can take over an hour to go up or down, and the locks are huge with room for six or more boats at a time, so you tend to spend quite a lot of time chatting to the people next to you, making it all very jolly and unstressful once you’re in.

There are downsides, and around the first corner after the Muirtown flight we met the first in the form of Caley Cruisers and LeBoat, Scotland’s answer to Hoseasons and the hire boats of the Norfolk Broads. Even the lock-keepers warned us about these, and tried to keep private yachts and hire boats apart for good reason: the hire companies appeared to encourage their customers to treat the boats like dodgems, evidenced by the huge gashes down the sides of each one. We quickly developed sympathy for them, however, as far from the hooligans their boat-driving suggested they were mainly polite, well-heeled Europeans on holiday who had not been briefed on anything other than full speed ahead. We initially worried about helping take their lines, or even giving patronising advice such as ‘it’s often better to put your fenders out before you hit the pontoon’ , in case they were offended, but even this masterpiece of ironic humour was taken gratefully as a piece of wisdom worth treasuring. Honest. We did actually see people arrive in the lock with their mooring lines still tightly tied onto the rail, and others approaching any pontoon at speed, 90 degrees to it, in the sure expectation of the bow thruster rotating the boat in under its own length. Surely ten minutes spent on briefing the basics would save quite a lot of damage to both boat and customer ego? Or perhaps it’s a way of generating employment opportunities for the glassfibre technicians of the Highlands.

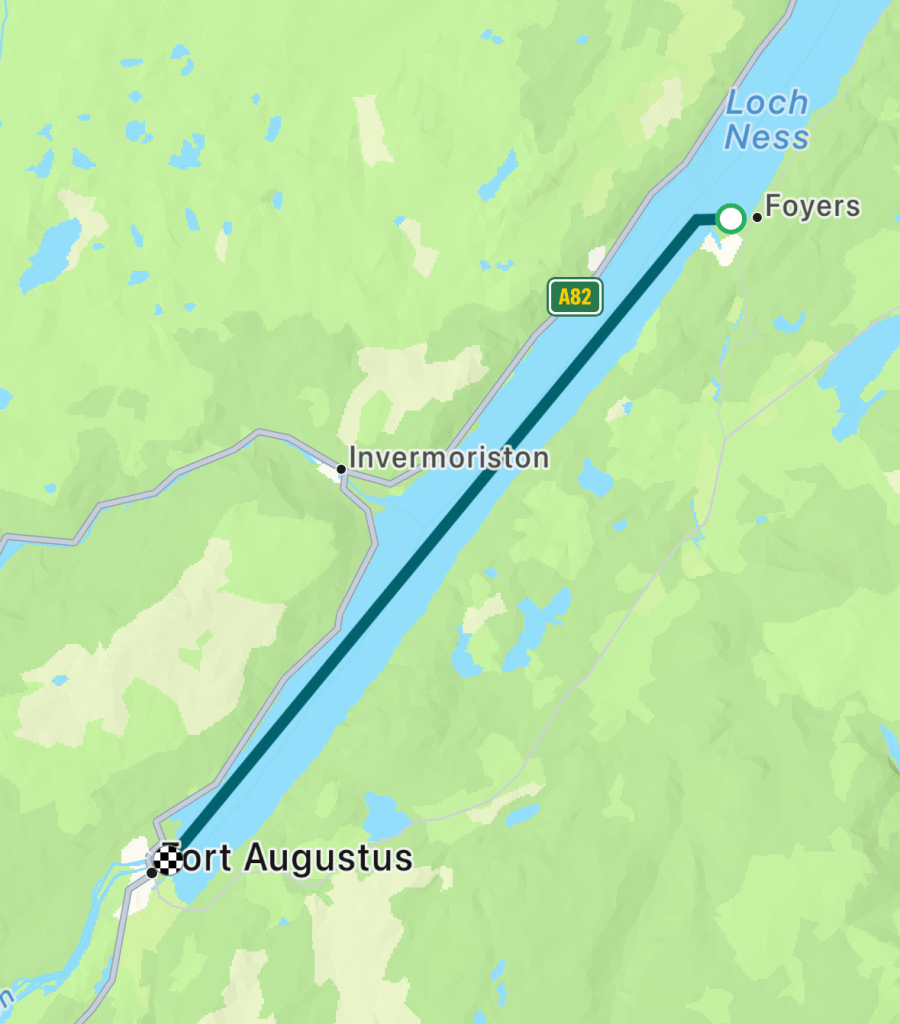

The other main downside is the very real risk of spending time in Fort Augustus, where the large flight of locks is surrounded by a tourist village selling Nessie souvenirs, nasty burgers and over-priced shortbread. It seems to be on every coach tour itinerary, just long enough for the contents of each coach to don a plastic poncho, take pictures of the boats in the locks, ask questions like ‘does your boat go on the sea?’ and complain about the midges (there weren’t any). I had a cunning plan to avoid this horror, which was to have a lazy lunch at anchor before heading out into the rather windy Loch Ness, where we had identified the only place on the whole loch where you could treat it like proper cruising by anchoring off a beach and going ashore for dinner.

This was a very strange experience: most of Loch Ness is well over 100 metres deep right up to the shoreline, but Foyers Bay is a little promontory on the south side opposite the main road where two rivers have deposited a small bank of shingle you can anchor on, so we did, and enjoyed the chance to get further away from the boat than the towpath for the only time in the whole canal by walking up the almost deserted hillside to a very remote hotel with amazing views over the loch. Sadly not of the boat: although we had anchored metres from the beach under a very effective shelter of pine woods, it was blowing over 20 knots and I was very pleased to get back to the beach to find Blue Moon still there, not making her own way back to Inverness. The only mishap came the following morning when in my eagerness to pull up the anchor I managed to pull us onto the shingle bank, but at least I can now say that not only have I sailed down Loch Ness, I have run aground in it, which might just be unique.

I say ‘sailed’ but it was more or less inevitable that we would motor the whole way, as the Great Glen is cleverly aligned South West so that the prevailing wind can blow straight up it without repetition, hesitation or deviation. We glared jealously at the one or two yachts passing us going north, relaxing with sails out while we bashed into quite substantial waves under engine – most of the time the lochs are less than a mile wide, so beating would have been very slow and rather painful.

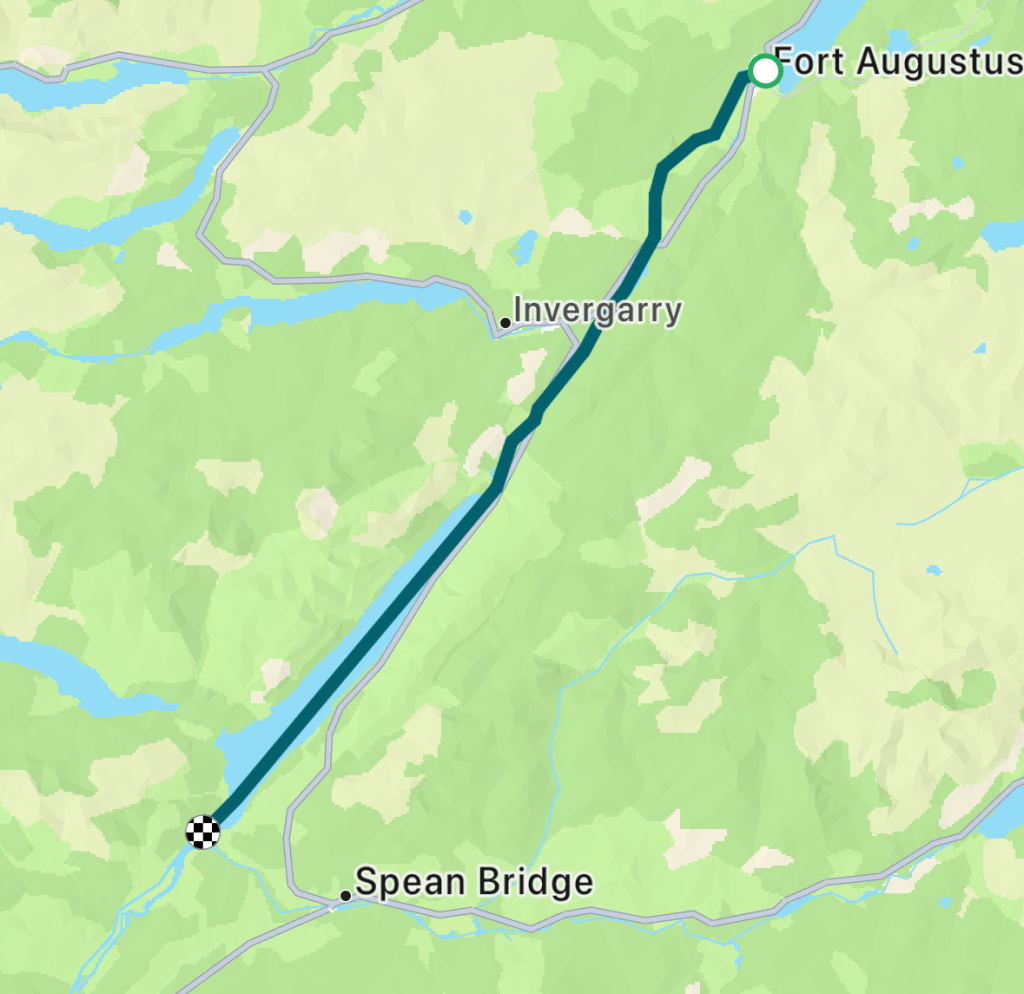

The need for speed was caused by a weather forecast which promised actual full-blooded gales the next day. We didn’t fancy motoring across Loch Lochy in a gale: in spite of its silly name it’s over ten miles long so perfectly capable of kicking up some nasty waves that would make for noisy, slow and wet progress. Our plan was to get across it that evening, leaving us with just a short bit of canal to motor down in the big wind the following day. Arriving at Fort Augustus this plan looked iffy: there was a queue of boats who’d foregone the pleasures of anchoring and spent the night there eating pancakes and candy floss so as to get a head start in the morning. This hold-up required some careful in-person pleading from me and Andrew as we tried to get the word ‘gale’ into our begging as many times as possible. In the middle of the Highlands, 30 miles from the nearest salt water, this seemed very peculiar but the boss keeper relented and laid on an extra flight for us and five hire boats.

Miraculously we survived, and even made friends with the German family in the boat behind who had seen the forecast and asked if it made sense to get across Loch Lochy this evening. Wearing designer raincoats under their hire boat lifejackets they were impeccably dressed for a slightly drizzly shopping trip in Hamburg, so I confirmed it was a good idea and awarded them many Sensible Skipper points. They too had a schedule: the day after next they were booked on the Jacobite steam train that played the part of the Hogwart’s Express; their son had just finished reading The Philosopher’s Stone and was beyond excited. He looked very precocious, and I suspect he had read it in English.

Then our one canal hiccup: the lock keepers are all in contact with each other and we heard the news ripple down the flight of locks: “Barry’s pontoons are full”. Barry, it was explained, was the keeper of the next lock, he was off on his lunch break and the waiting pontoons now had this morning’s queue of boats from Fort Augustus tied onto them, would we mind waiting here? This would kybosh our plans: if we couldn’t get to the locks into Loch Lochy before they closed for the night we would be stuck until the gale arrived. We and the Germans independently formulated the cunning plan of motoring very slowly to arrive at Barry’s lock just as he finished lunch, only to find no boats waiting and Barry himself cheerily heading off for his lunch break. He’d cleared the queue but created an hour’s delay for us.

This put the pressure on: we couldn’t afford a single further delay now and we still had three locks and two swing bridges to go. All good until we found ourselves behind a large cruiser whose occupants were not the least bit fussed about the gale as their boat was massive enough to shoulder it aside. They told us they were enjoying taking it easy in the canal and so it proved – they were going so slowly that one of the bridge keepers called them up on the radio to tell them to hurry up as they were delaying the road traffic. Eventually we made it out into Loch Oich and there was room to behave like Oichs: we floored the throttle and pulled out to overtake. The Germans did the same on the other side, rather more quickly in a dedicated motor boat. It took us at least five minutes to overhaul the yacht, blushing deep red at such un-seamanlike, un-sportsmanlike and un-canal-like behaviour, but it did mean that we were now in front and could radio ahead to the remaining bridge and locks. Places booked, we were through and squeaked out into Loch Lochy luckily just before the lock-keepers clocked off. Enough alliteration?

On the one hand, we had motored full tilt through some of the most spectacular scenery…

…and Georgian engineering…

…that we should have been relaxing enjoying; on the other, we were tied up on a very sheltered pontoon long before the gale started howling up the glen. There were no facilities at all up here in the mountains, but we came prepared and ate haggis and neeps in the cockpit in sight of Ben Nevis. Or at least the clouds on it.

The friendly Germans came past. “There is no pub”, they called, mournfully. “No”, we replied, having been reassured they did have some food, “but there is a view”.

It was hard not to feel smug next morning when we heard tales from the bedraggled arrivals of motoring into big waves across Loch Lochy. We could now relax, enjoy a late breakfast on an even keel, and motor the two hours to the top of Neptune’s Staircase outside Fort William in time for lunch.

Marnie was due home the next morning but Andrew and I had planned to spend a day climbing Ben Nevis next door before tackling the legendary Neptune’s Staircase. Sadly we both agreed that this would be a pointless exercise with 100% low cloud cover, savage rain squalls and 50 knot gusts on the top, so we decided to head down the staircase and out to sea where it was only forecast to blow 25 knots. Fortified by an excellent evening in a surprisingly hospitable pub in the middle of a housing estate we headed down the eight lock flight in the company of a huge catamaran, a very fancy Danish yacht and a motorsailer belonging to a young couple from Suffolk and Inverness with a small baby and the cutest dog ever seen on a yacht (we didn’t see the baby so can’t vouch for its cuteness). She had grown up sailing her parents’ Parker on the Orwell so we ended up having two hours of East Coast conversations covering mud, barges and Ipswich Town’s chances in the Premier League as we descended the longest lock flight in Britain.

We just managed to get to the bottom as the baby woke up, then it was through the West Highland Railway line (an unusual experience)…

…one more lock and then the sea lock. This was oddly unsettling: after five days of sheltered fresh water it felt very peculiar to be looking at seaweed and listening to the sound of the wind howling in the rigging.

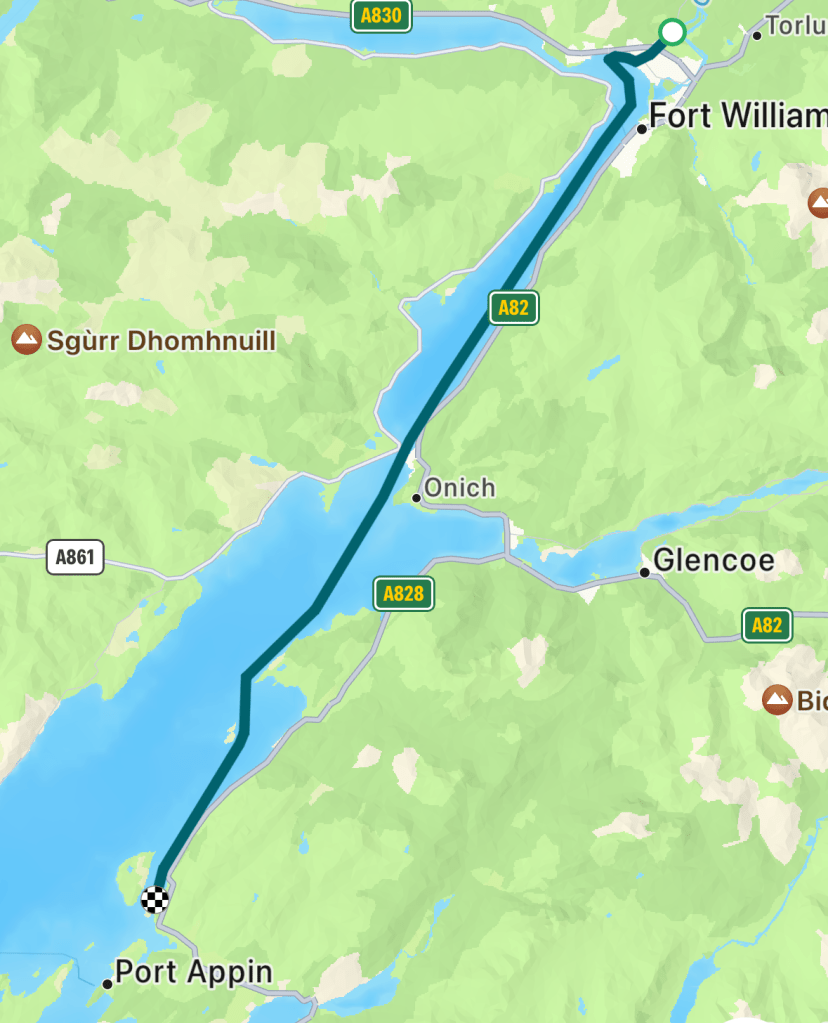

Too soon we were spat out into the grey salty murk, and since Loch Linnhe really is just a continuation of the Great Glen and we hoped to persuade the pub in Appin to give us steak and chips it was more heavy motoring – this time into bigger waves and an adverse tide.

We failed with the pub – the reason they weren’t answering the phone was that it was the day of the Appin Show, and at 1800 when we walked into the totally packed bar we were already the only sober people so we had to make do with beer in the pub garden and emergency sausages on board.

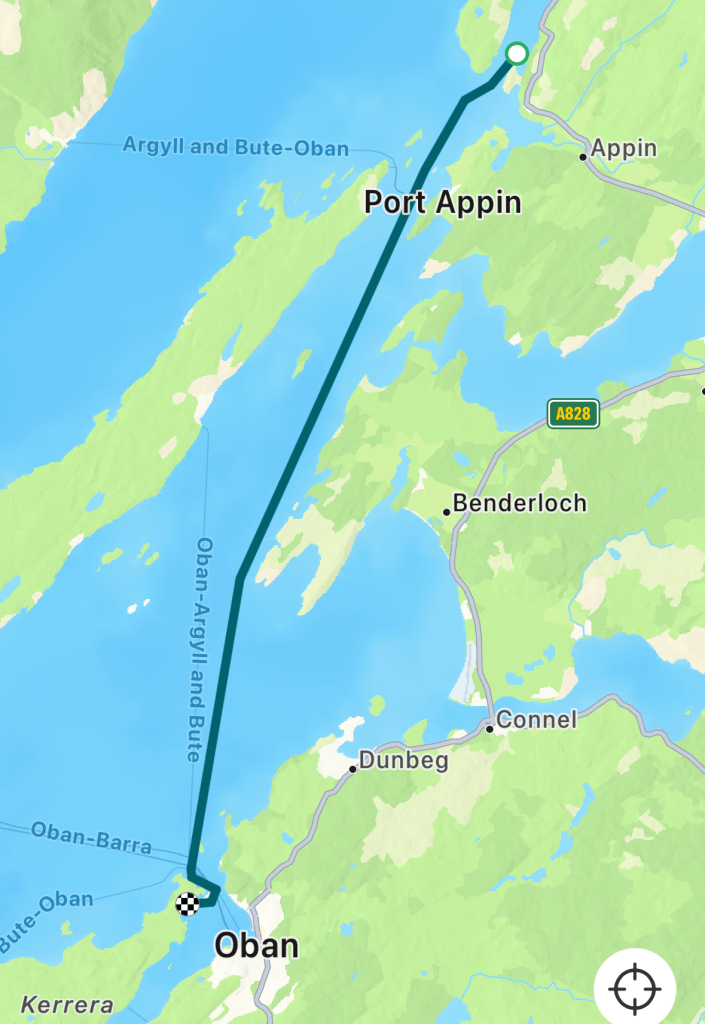

It was worth the motoring though for a grand if short sail next morning down to Kerrera Marina near Oban where we were booked in to have the leaky window finally fixed, the unreliable outboard fettled and the overworked main engine serviced. After ten weeks out in the Far Northwest, North and Northeast this felt like coming home, especially when we went to the bar to find that they had put up the burgee I’d given them:

Oban was the main site for the flying boats that covered WW2 Atlantic convoys and the marina is on the site of the base. They’d been interested to hear that the Short Sunderland – a model of which hangs in the bar – was originally built in Rochester just up the river from where the MYC clubhouse then was. Or at least they’d been kind enough to pretend they were, and hang the flag up. It’s next to the Sinister Legs of Man YC though, and that’s where I’ll be in a few weeks on the way back to Liverpool. But after this Tour of the North…

… I think I’ve earned a week or two pottering around the softer bits of the West Coast with some new guests before heading South. If only the weather would play ball: needless to say as soon as I jumped on the train in Oban the sun came out, and as soon as I got off in London Storm Lilian arrived to dump a ridiculous amount of rain and wind on me, while Northwest Scotland enjoyed its first sustained sunshine for a month.

Leave a comment