Scrabster is a great name don’t you think? I did, a few years back when I started dreaming of making this trip. I was idly looking along the very top of mainland Britain, i.e. the north Scottish coast, and wondering about how very straight and empty and bleak it looked, and how there were no roads and only one or two actual places. The only place I had heard of was Thurso, and next to it what looked like a tiny village with the odd name of Scrabster.

Then I started doing my research and discovered that Scrabster is the absolute definition of a working fishing and ferry port. At the very top of the A9 it’s where to catch the ferry to Orkney and where to come if you want to load your articulated lorry with fresh fish: the pilot book explains that yachts are welcome but only if there’s room among the fishing boats.This sounded like the kind of experience I was after, and for years since my little mental test when refitting the boat was ‘how will this be to live with when I’m spending days storm-bound somewhere wet and cold like Scrabster?”. Well I am very chuffed to have spent a couple of days in Scrabster, luckily not storm-bound and not that wet either, although it absolutely lived up to expectations in its uncompromising fishiness.

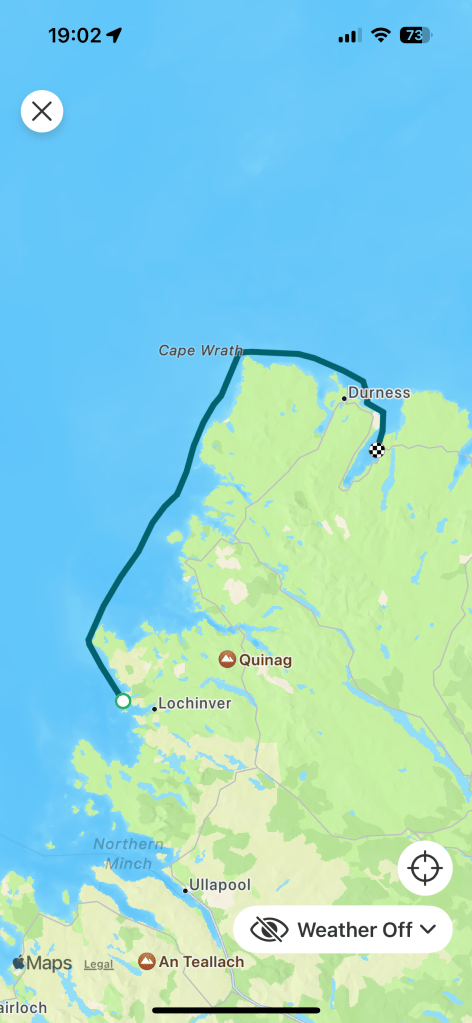

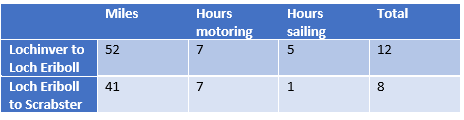

The more engaged reader also deserves a word of explanation before I go further, if you’re engaged enough to remember that the plan this year had been to head as far north as Kylescu before going back south to Oban, where I would meet assorted guests who would accompany me through the Caledonian Canal to Inverness, leaving me to explore the Moray Firth for a week or two before heading back down the canal to start wandering south to Liverpool. The north coast was to be for next year, on the way to and from Orkney and Shetland. Well, the prop seal put one of David the Engineer’s spanners in that particular works: unable to get south after the repairs in time to meet the guests, plans were remade, and even the most landlubberly guest noticed that Locvhinver is a lot nearer to the north coast than it is to Oban, and it would make sense to go to Inverness around the top of Scotland, thence one way down the canal back to Fort William and Oban. Sadly the change of date meant a change of guest as Sarah had booked herself on a much more sensible holiday involving trains, sunshine and mediterranean food, but more of that later. First, over the top it was, and with places like Cape Wrath and the Pentland Firth to negotiate, I was a touch apprenhensive.

Apprehension was not helped by a fairly stressful departure from Lochinver. I spent a whole day (precisely 12 hours this time, starting from Kidderminster not London) on trains and buses, along with half an hour in a taxi to Wolverhampton driven most improbably by a man who had spent his working life installing the mobile masts all over the West Coast of Scotland. He had fallen in love with the place, went back twice a year for holidays, and knew everywhere I’d been. I wanted to thank him for the mobile coverage but was preoccupied by having lost my wallet and booked the train for the next day by mistake.

These errors were easily rectified, unlike the range of subsequent delays: first to the two trains, who managed to connect as planned only by virtue of the second being even later than the first, but only by a few minutes. Then the bus from Inverness to Ullapool, which I had just made in spite of the delays, sat motionless for twenty minutes waiting for a passenger on a connecting bus. I’d never heard of this sort of guaranteed connection on a bus, nor had most of the passengers or the driver by the looks of it, as there was a lot of stressing on all sides about the ferries and buses that would be missed at the other end. I only describe these delays because the most extraordinarily Highland thing then happened: I mentioned that I would miss my Lochinver bus and the driver, having tried and failed to contact the bus company to ask them to wait for me, said “last chance: my friend driving the other bus is best friends with the lady driving the Lochinver bus this afternoon; I’ll message her and see what happens.” 90 minutes of heart in mouth later (it was the last bus to Lochinver) and we pulled into Ullapool to see the little bus waiting for me. I thanked the driver profusely, as a Londoner who is lucky to catch a scheduled bus let alone have it wait, and apologised to the three passengers (two of whom had been on the bus out a week ago, honest) that I had made them late. “Don’t you worry”, they all chorused, “we’ve all been there.” I mentioned this astonishing act of kindness to Linda in the harbour office next morning (I am now on first name terms with all the harbour staff). “Oh yes,,” she said, “that’s my sister-in-law, of course she’d wait.” Later in the day I saw the bus coming into the village (on time); Linda’s sister-in-law recognised me and waved enthusiastically. I can see the attraction of living here, although the journey also made me very aware of the downsides.

The second piece of stress involved re-launching the boat, and I only mention it in the hopes that by publicly confessing my sins I will in due course be forgiven. It was very windy, and they asked if I really wanted to launch. I did, as there would a gentle breeze to round Cape Wrath the next day, and I wanted to get north that afternoon when the wind dropped. I’d also spotted a nice space on the downwind (safe) end of the pontoon with loads of room to come alongside for a while to check for leaks. Launch went fine, nothing leaked (not even the impeller I had changed), and I headed for the pontoon. Annoyingly a bunch of well-intentioned people had gathered near a much smaller space and were waiting to take my lines. A huge gust sideways as I came alongside, they missed the rope I had tried to throw them, and before I could even swear I was blown sideways onto the little boat next door with a nasty crunch. So embarassing: I have hit plenty of people while racing, it’s frowned on but kind of inevitable, but I have never hit anyone cruising, and I had rather hoped never to. I felt totally ashamed, even more so when the sympathetic onlooker/helpers started wittering on about how I had so nearly made it with such skill in conditions that they wouldn’t have dreamed of coming into that space in. I bit my tongue and waited for the owner to come down and shout at me. This being Lochinver he was sweetness and light, it was only a couple of inches of rubbing strake (true, even I had to admit it was very minor, but still…), he could easily get a piece of teak to mend it and would let me know how much the teak cost. Nothing more. I felt even worse, although he assured me that he liked nothing more than a bit of boat woodwork.

Needless to say, the wind did not moderate in time and in any case after all that I needed a lie down, so it was early next morning when I set off for the even further north. There was just enough wind to sail, and for most of the morning I entertained a ridiculous notion that my dream of gybing around Cape Wrath with the spinnaker up might come true. I got particularly excited about this when I was joined by a group of three yachts coming out of Kinlochbervie at a more sensible hour, which reassured me I had got the timing right and also presented a chance to show off.

Sadly the wind died as soon as I caught them up, so it was engines on all round.

I’d read up a lot about Cape Wrath and the pilot books are full of warnings appropriate to a very sharp headland with a name like Wrath. Even experienced sailors I’ve met say things like don’t even think about it in anything over a Force 4; one even said don’t go round it after July. Sadly, like so many others, the word has nothing to do with anger, and it’s not even pronounced ‘wrath’ but ‘rath’ with a short ‘a’: it is Old Norse for a corner, which makes Cape Corner something of a tautology. Having witnessed its tides in a flat clam at slack water I would not like to be there in much more of either, but today it was so calm that I cheekily snuck inside the terrifying-even-in-a-flat-calm Duslic Rock and thereby stole a march on my competitors.

I was lucky: in such benign conditions I could relax and admire the astonishing scenery as the jagged headlands of the north west coast gave way to the vertical cliffs and sea stacks of the north north. There were sea caves with waves breaking ominously inside them in spite of the calm, and more puffins, guillemots, razorbills and what-have-you than I had seen in one place yet this year, all seemingly with nothing to do but sit on the water and wait for a yacht to come by so that they could dive or attempt to fly, both rather comically.

By early evening I had ticked another bucket off the list in the form of Loch Eriboll. Reading all about this totally deserted loch miles from anywhere again suggested it would be either terrible or horrible or perhaps both, but on a sunny late July evening with no wind to speak of it was simply stunning to be there in complete silence; or it would have been were it not for the occasional campervan out late on the NC500 which follows the loch around. Even they couldn’t spoil the moment: in the distance Ben Hope, the most northerly Munro, towered over the nearer hills while closer at hand sheep wandered around on the beach looking for grass in a way that confirmed all anti-intellectual sheep prejudices. It was all so lovely, and I was so chuffed at not wrecking myself on Cape Wrath, that I could hardly think of it as bleak in spite of all my imagining, but I suspect that in January in a big northerly gale the couple of hours of daylight would not be quite so uplifting.

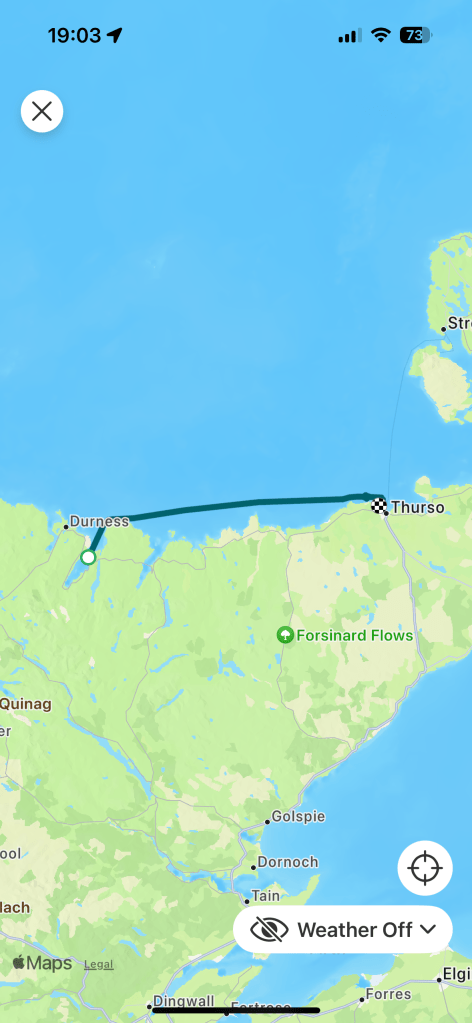

And so to Scrabster, and what a complete change. The pilot identifies a headland called Strathy Point as the place where the mountains stop and the flat lands begin and it was absolutely right: it was if someone had flicked a switch marked ‘mountains’ and they had all sunk into the ground like a Bond villain’s secret weapon. Suddenly everything felt different, and even this far north all of a sudden I felt more at home, because we were heading for the North Sea (OK, still a way off yet) and I could almost have been looking at parts of Kent, albeit with something higher than the North Downs in the background. With the flatter ground everything else became more familair too, except that it wasn’t after months on the West Coast: there were hamlets rather than single houses, with more than one road in and out. There were farms with fields and barns and tractors. There were cars and occasionally vans and lorries doing more than 20mph on roads that were oddly straight. There was even a lighthouse on every headland, rather than one every 50 miles.

Mind you, it was all still very empty and bleak-looking, even with the sun out, and with a light northerly breeze I was motor-sailing into it and getting very cold indeed. So although Scrabster was looking sunny and as pretty as it ever could (not very, but prettier than Lowestoft or Grimsby) I was wearing a woolly hat when I tied up. On the first day of August.

In spite of the very obvious emphasis on fish and ferries, Scrabster makes a point of saying that yachts are welcome, pointedly adding ‘if space is available’. So although I was sorry to miss out on the ‘picturesque’ inner harbour…

…I was very grateful to be given a nice new pontoon on the lifeboat pier, and someone came down from the harbour office to take my lines and welcome me in. Being a local fisherman as well, he turned out to be the right person to get advice from on the next leg: the Pentland Firth, probably the scariest place I’ve sailed through yet, but that comes later.

Scrabster turns out to be backed by the greenest cliffs I have ever seen, and surrounded by rugged, bleak but fascinating countryside. In every other respect it lived up to its name: the fish harbour occupies in effect a good-sized industrial estate with fish wholesalers in modern offices around fish warehouses and fish truck depots, all of which have a distinctly fishy aroma 24 hours a day.

By making yachts welcome, what they mean is that yachtsmen are welcome to use the fish truckers’ shower but after Lochinver I was prepared for this, even the cycle ride to get there across the harbour. A couple of times a day big trawlers would come in and tie up opposite and do something invariably noisy: one appeared to pressure wash something all night, or perhaps it was welding. Three times a day the Orkney ferry calls with a few hundred cars going through the village. Even the Border Force and the lifeboat came in and out in the two days I was there, so it wasn’t the most relaxing place, but after the emptiness of the north west it made a very welcome change. I cycled into Thurso to find a normal-sized Tesco, a town with a high street and lots of civic pride, and even two roundabouts, something never seen further west. Even the place names have changed – places like Scrabster and Lybster and Nybster sound pure Viking, and there was no Gaelic on the roadsigns.

A walk on the cliffs around Scrabster was a great way to get out of the fishy environs: there is a decommissioned lighthouse which looks like a fabulous family home…

…a lot of sea caves that you could easily fall down a hole into…

and my first ever experience of being attacked by seagulls for a reason other than stealing my chips. I guessed it was because they just don’t get many visitors.

Then it began to rain, and my image of the rainy day in Scrabster became a reality. And I am sorry to say I lasted less than half an hour, because outside the ferry terminal I had seen an Enterprise Car Club car and I am a member. I should have spent the afternoon snugged up down below, looking at the rain and writing a blog post before reading an improving book. Instead, I jumped into the car and drove to John O’ Groats, which is only 15 miles or so down the road. This turned out to be an excellent move for two reasons: first, miraculously the rain only went as far as Thurso and as soon as I headed East it stopped, so I spent most of the afternoon looking at clouds rather than sitting under them. Second, it gave me a chance to check out the Pentland Firth before I sailed through it next day.

In due course the second reason didn’t seem so excellent: the water didn’t look too bad but John O’ Groats is more focused on shipwrecks and the terrifying tides of the Firth than it is on being a long way from Land’s End. At every turn there was another information board explaining how all the Atlantic and all the North Sea took turns to squeeeze through the gap between Orkney and the mainland, and how that caused whirlpools and overfalls and things called ‘roosts’ which are patches of ferocious standing waves. I’d been reading about these, with ominous names like ‘The Swinkie’ and ‘The Boar of Duncansby’; even ‘The Merry Men of Mey’ was obviously ironically named as the pilot book, alongside warnings marked in red this time, bluntly said “under no circumstances should it be attempted by small craft.” Reading this information on boards intended for tourists made it all a bit more scary, illustrated as they were by details of actual shipwrecks with massive loss of life, which pilot books thankfully keep quiet about. As recently as 2015 it turns out that a largish Polish coaster was capsized in a storm in the very bit of water I was about to sail through, with all eleven sailors drowned.

It finally came on to rain quite hard where I was, so I took the obligatory selfie…

…and tried to banish all thoughts of roosts and shipwrecks in the cafe with a surprisingly nice coconut slice and a flat white. I say surprising, because I have been to Lands End and it is a perfectly ghastly hell-hole of tourist rip-offery; John O’ Groats is rather civilised, low-key and, well, Scottish: the opposite of Lands End in more ways than just geography. And of course it isn’t even that: the most northerly piece of mainland Britain is Dunnet Head to the west, and the most north-easterly is Duncansby Head to the (surprise) north-east, but John O’ Groats is refreshingly open about this, pointing out that it is the ‘most north-easterly settlement’. That doesn’t wash either: no-one talks about walking/cycling/skipping from Sennen to John O’ Groats, do they? But somewhow I liked it all the more for the honesty, and the fact that it rained less than in Scrabster, where I doubt they serve flat whites at all.

Leave a comment