“Hang on a minute” I hear the whisky geeks cry, “you claim to have walked, cycled, or sailed past every distillery on Islay, but you have only mentioned Port Ellen, Laphroaig, Lagavulin, Kilchoman, Bruichladdich, Port Charlotte, Bowmore, Ardbeg and the one that’s still being built, which the internet tells me is to be called Portintruan. What about Caol Ila, Bunnhabhain and that brand new one, Ardnahoe?” Calm down, readers, we did them too, but by water. Read on.

You’ll remember no doubt that the we’d spent two days mainly on land because it was blowing very hard. It carried on blowing fairly hard for another couple of days, but we had a schedule – not just to Ardbeg, but on to Jura to tick another box, this one slightly healthier. We all wanted to climb the Paps of Jura, three very distinctive mountains which I had spent large parts of last year looking at, as on a clear day they are visible from Kintyre, Antrim, Oban and beyond. Their distinctive shape also gives them their name, about which I will not comment further but direct you to Google, but we were more interested in the fact that the view from the top is described as one of the best in Scotland. You’ll notice that I am not offering a personal opinion there, in spite of having climbed one, for reasons that you can probably already guess at.

The wind, for once, has been kind to us this week. Or sort of, it could have been kinder but I have learned not to complain. On the one hand, as soon as Andrew and Roger arrived for a journey that was predominantly heading North West, the wind went into that direction, stayed there, and blew all week, sometimes very hard indeed. On the other, we never actually had to tack, and once it even blew from behind us for a little bit. Admittedly we had cheated on the no-tacking thing by motoring out of Ballycastle, but we all agreed that beating through a notorious tide race with the tide against a 28-knot breeze was frankly bonkers, whereas motoring into it was simply the act of three desperate whisky lovers.

So it was that we dropped the mooring at Ardbeg, cockily threaded our way through the absurdly rocky shortcut and headed up past the corner of Islay to its underpopulated neighbour, Jura. My previous visits last year had included sunbathing and swimming around the boat, both in June and September, so it was a bit of a surprise to find it absurdly cold as well as windy and occasionally very wet. However, contrary to expectations and belief, we made it the whole way on the wind without tacking, so we didn’t complain, and I was very proud of my new cruising skills when we arrived at our intended anchorage at the north of Loch na Mile, found the wind howling down the valley, and cunningly anchored instead behind a small plantation. My smugness only lasted until dark, when the wind noticed we’d gone to bed, changed direction and blew around the trees right at us. This is not fair if, like me, your bed is at the front of the boat as the anchor strops (stretchy bits of rope that act like shock absorbers on the anchor chain) creak and groan all night next to your ears, while the wind howls in the rigging above.

So I was the bleariest of the three when we dinghied ashore in the middle of the famous wilderness of Jura to be greeted by two cheerful gentlemen from Glasgow who had spent the night rather more comfortably in a tent on the beach, which wasn’t being blown through 90 degrees every 30 seconds. Suitably impressed by our intention to climb the Paps, they did remark that we had chosen a good day for it as there wasn’t a cloud in the sky, and buoyed by expectation we headed off, up a road, up a path, over a bridge and into a bog. Jura is largely made of bog, except for the bits that are made of rock, but the sort-of path avoided most of the wettest bits, and we settled down to a long but lovely trek up past an inland loch with the Paps smiling down at us from a blue sky.

Uh-oh. See those little fluffy clouds? So did we, but it’s not the kind of terrain where you can suddenly sprint for the summit. Sure enough, the closer we got the steeper it got, the cloudier it got, the slower it got and so on. A stag appeared on the horizon to remind us we were in Scotland and laugh at our presumption that we would see a view. And indeed, after a whole morning of blue sky, we duly climbed up a steep rocky face into a cold, damp cloud. T shirts to fleeces and hats in under five minutes. A rocky scramble and we were at the top, where that pesky wind was now hurling clouds at us at 25 knots. Visibility around six yards.

That’s the beautiful views stretching up to Ben Nevis behind us. Apparently.

Rather optimistically, we decided to have lunch to give the clouds time to disappear. Yes, laugh if you will at the thought of three daft sailors hunkered down inside a ring of stones some helpful mountaineers had built around the trig point, presumably so that daft sailors could sit there out of the wind and eat their picnics. They had also installed a 4G mobile mast somewhere nearby (as is the case on most Scottish islands) so we could consult various weather apps promising a sunny, cloud-free day.

In a rare moment of sense we decided to head down before we got hypothermia, and this brought its own challenges. The first was one of those narrow ridges with steep sides that mountaineers tend to fall off…

…followed shortly by a series of extraordinarily steep and slippery screes, which you could only really negotiate by surfing down. Not being a skier (unlike Roger and Andrew) perhaps meant I was less aware of the potential downsides of such a manoeuvre and was considered reckless, but we each managed not to break any bones.

But the greatest challenge was the way the cloud began to thin as soon as we left the summit, tempting us with glimpses of far-off peaks on Arran, Islay, Colonsay, even Antrim on occasion. This made scree-surfing even more excited as it was almost impossible not to look at the views instead of the rocks ahead. Needless to say, as soon as we were back on relatively safe grass and rocks that were fixed to the rest of Scotland, the clouds pushed off completely, confirming that the only two hours that the views weren’t available from the summit were the two we were there. But what we did get was pretty decent.

Back out of the cloud there was the remains of the unexpected day-long heatwave. Someone on the beach was swimming (admittedly they were clearly Scottish, and squeaking loudly) and it all looked like the Caribbean again.

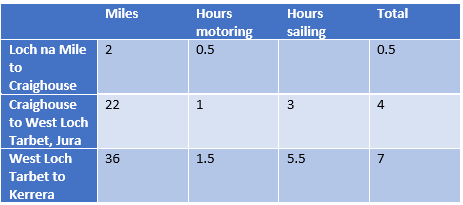

We motored the two miles down to Craighouse where we celebrated our chilly ascent at the Jura Hotel with people who’d spent the day in shorts. Although this was the day after the Jura distillery’s open day (they get treated as part of the Islay festival, a bit like Australia and Eurovision I suppose) there was no sign of any Laphroaig-esque wind down, most of the island’s mighty population of a couple of hundred seemed to be in or around their only pub.

In search of proper Jura isolation we had planned a night in West Loch Tarbet. This is another place that had long been on my must-visit list, being described as the most remote loch south of Ardnamurchan. Being half way up Jura helps in that regard, and being on the West Coast seals it. From the corner by Craighouse, where the Australian hedge fund kid is building an amazing golf resort, we saw not a single house, let alone road or track, on the entire coast of the island.

To start with, our route took us up the Sound of Islay between the two islands, which allowed us to contrats the barren Jura shore with Islay, where our remaining distilleries lined up in a row, along with the villages each one supports. This is where the wind did us its second favour: most sounds are opportunities for the wind to blow straight up and down, regardless of the general wind direction elsewhere. Faced with a vaguely north westerly wind and a definitely west of north Sound, we feared the worst, but to our astonishment the wind blew sideways enough to let us sail the whole way, helped by a massive tide. On and into the wilds of West Loch Tarbet, where we threaded our way through a couple of very narrow rocky passages to anchor in a bay with the only thing resembling a house on that side of the island, and then only a bothy for bonkers bog-walkers to sleep in. A quick visit confirmed there are quite a few of these as they wrote their names in the visitors’ book and later that evening there were lights in the windows. Unless, of course…

You’ll notice that by now the weather had, as they say, closed in. That’s the boat in the middle of the picture, a full 200 metres away and barely visible. It was blowing very hard even though we were sheltered behind that big hill on the right, it was absolutely freezing cold and we were exposed to a full afternoon and night of unremitting Scottish Dreich. Roger and I took the dinghy up through another series of famously tortuous rocky passages to what’s called the Top Pool, miles inland and miles from anywhere (the pilot book warns against taking actual yachts there, although brave souls do) and we ended up sodden and half-frozen to the dinghy. We also came across a small motorboat from West Mersea (in Essex) which seemed totally implausible. This really was wilderness, as for the first time we found ourselves with no mobile signal at all, which was a shame because the weather forecast was busy changing its mind and lining up some full-on gales for the next few days. Andrew and I got a quick snatch of information when we climbed the hill behind the bothy, and it was enough – confirmed the next morning – to know that our plan of three days exploring the little islands between here and Oban was a non-starter: we needed to be tied up on Monday evening before it got too feisty.

Luckily the wind, and the weather in general, had one last favour to offer us. As we motored out of West Loch Tarbet the sun came out, the wind gradually swung round and as we bore away past the Corryvreckan and Grey Dogs and through The Great Race (yes, all these places are real and mainly rather scary), for the only time this week the wind was with us, so we wasted no time putting up one spinnaker and then the other, with the result that we ended up in Kerrera Marina opposite Oban in plenty of time to bag a pontoon, with the satisfaction of our last sailing day in sparkling sunshine doing nearly nine knots with the spinnaker up in 18 knots of breeze.

We also were treated to the spectacle of a large American yacht hurtling up from the South of Mull under a massive spinnaker, gybing and wrapping it around his forestay. The poor guy was short-handed and totally unable to free the wrap, so while we showed off with two gybes and a spinnaker drop at the top of Kerrera Sound, he came belting up behind and, unable to free the kite, sailed straight past and out the other end via some nasty rocks on the point. Two hours and lots of radio conversations later he limped into the marina; we have no idea what combination of bread knives, bosuns chairs and possibly flare guns had got the spinnaker down, but he clearly slunk off home as we couldn’t find him, much as we worked on our dropping the ‘we were the boat in front of you gybing faultlessly’ into conversation, which is probably just as well as I would rather not tempt that particular fate.

That was it as far as sailing is concerned, but a high note to go out on. The wind went into the high 20s and stayed there, the temperature dropped to 5 degrees and there was snow on Colonsay next door. In June. So we stayed tied onto a nice solid pontoon for two more days, donned our walking boots and hit the hills of Kerrera and Oban. Which, luckily, are rather nicer than we expected as they have amazing views…

…and even a fairytale ruined castle to explore:

It’s a sign of how this trip has made the extraordinary normal that arriving in Oban, and Kerrera Marina in particular, felt like coming home, in spite of the rocks and mountains all around, and it being at the other end of the country from home, and the friendly people at the marina remembered us from last year (rather improbably one of the owners had just won the World White Water Rafting Championships so there was cake). Sadly the warmth of the welcome wasn’t matched by the ambient temperature which remained in the snow zone the whole time and meant putting the heater on all evening. This made it a good time to head to real home for a few days: as we plonked ourselves down in the 0850 to Glasgow we agreed it was the first time we’d been warm all week, and arriving at Euston in fleeces was like when you’re felled by the heat as you walk off the plane on holiday in Greece and remember you’re wearing the coat that was essential at Gatwick that morning. Sadly it looks as if this freak cold isn’t going anywhere, as my next guest is due and after a weekend of normality I’m back in fleece and the boat heater is on again…

Leave a comment